International Study Brings Researchers Closer to Personalized Depression Treatments

Abstract

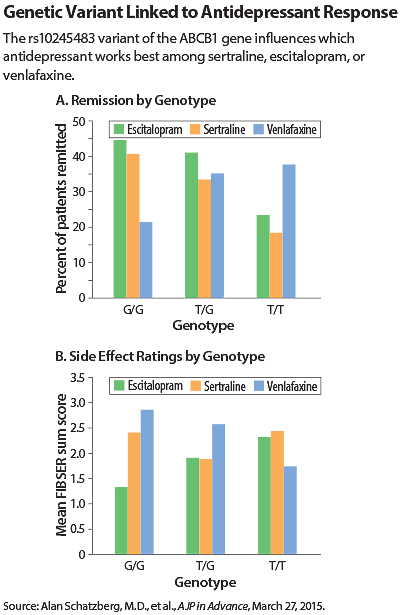

While iSPOT-D researchers determine that a patient’s depression subtype diagnosis fails to predict response to treatment, recent data suggest a genetic variant of ABCB1 might be able to do just that.

Two related studies published in AJP in Advance on March 27 have provided some positive and negative results in the continued search for more personalized antidepressant therapies.

Both sets of findings arose from the International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D), an international effort that aims to identify markers that can predict how people with depression respond to one of three frontline medications: escitalopram, sertraline, and extended-release venlafaxine.

“This is a real-world study,” explained Alan Schatzberg, M.D., the Kenneth T. Norris Jr. Professor of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University and director of Stanford’s Mood Disorders Center. “A lot of the [iSPOT-D] participants came from primary care settings or psychiatrists’ offices, and the doses we are using are in line with standard prescriptions, so the findings should have practical meaning.”

The first study explored whether a patient’s depression subtype might predict his or her antidepressant response; subtypes, which are based on symptom presentation, are generally categorized as melancholic, anxious, or atypical depression. Recent studies have suggested these groupings are unable to reliably predict how well a patient might respond to antidepressants or which medication would have the best outcome.

As highlighted in the AJP in Advance study, part of the problem is that patients do not fall neatly into a particular subtype. Of the 1,008 participants in the study, 39 percent exhibited a pure depressive subtype, 36 percent met criteria for more than one subtype, and 25 percent did not fit into any subtype, the iSPOT-D researchers found.

When the researchers compared how the members of each group responded to eight weeks of escitalopram, sertraline, or extended-release venlafaxine, they found that all subtype groups exhibited a similar reduction in symptom severity and rate of remission.

“What this tells us is that we should not think too categorically when assessing depression,” said Schatzberg, who is a part of the iSPOT-D team and an author on both AJP in Advance studies. “And this falls in line with changes that were made in DSM-5 to remove categorical diagnosis and to think more dimensionally.”

Schatzberg added that—along those lines of dimensional assessment—the data suggested that the severity of anxiety might predict how well a patient responds, but more work is needed.

The second AJP in Advance study involved a genetic instead of clinical marker. In this analysis, the researchers examined 683 patients taking one of the three drugs and compared the efficacy and degree of side effects to the sequence of each patient’s ABCB1 gene.

ABCB1 encodes a protein called P-glycoprotein, which is a molecular pump that transports chemicals out of the brain. Small genetic changes in ABCB1 might affect how well this pump acts on certain antidepressants, enabling the drugs to stay in the brain longer.

The authors identified an ABCB1 variant called rs10245483 that had a significant effect on drug activity, though this effect differed according to the medication. For instance, people who had two copies of the G variant, which is more common, responded better and had fewer side effects with escitalopram and sertraline while people with the less common T variant responded better and had fewer side effects with venlafaxine.

The T variant also displayed another unusual feature, in that patients with this variant responded better to venlafaxine if their thinking was impaired. “This goes against the general trend that patients who have poorer cognition don’t respond as well to antidepressants,” Schatzberg told Psychiatric News. “This variant could override another predictive factor.”

Schatzberg noted that more genetic studies are coming down the pipeline, and those results should uncover additional biomarkers that when combined might yield even more personalized therapies.

The possibilities are not limited to genetic signatures or symptom severity; iSPOT-D is currently the largest personalized medicine research study in mental health, and it is assessing over 165 different measures, including a host of clinical and neuropsychiatric information as well as data obtained from brain imaging. More information is available here.

As part of iSPOT-D, these studies were supported by Brain Resources Ltd. ■