All Hands on Deck

Abstract

The concept of integrating behavioral health services into primary care is powerful and increasingly recognized by health care providers and payers, but even the most evidence-based approaches such as collaborative care for depression won’t deliver on their promise if they are not implemented effectively. Effective behavioral health care is best delivered by a cohesive team that shares information and coordinates care. Such teams may include patients, family members, trained peers, and a range of professionals including mental health counselors, nurses, social workers, primary care providers, psychologists, and psychiatrists.

In an earlier column (October 17, 2014), I wrote that some of the most commonly used approaches to integrating behavioral health care are highly complementary. Programs such as the Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Project and the Partnership Access Line in Washington state improve access to specialty consultation for primary care providers (PCPs) caring for children with mental health and substance use problems. On-site behavioral health consultant (BHC) models provide welcome access to behavioral health services in primary care. For patients with more severe and persistent problems such as major depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, or other chronic or recurrent behavioral health conditions, the strongest evidence is for systematic collaborative care (CC) programs that are based on sound principles of chronic illness care.

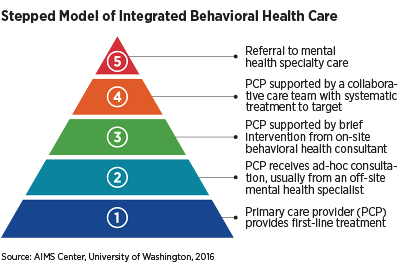

At this point, I believe that primary care settings are best served by a multi-tiered/stepped care approach that provides increasing levels of behavioral health specialist involvement (see figure on facing page). A patient is moved up to the next tier when he/she is not improving as expected. Levels of care may include the following:

Primary care practices screen patients for common mental health and substance use problems, and PCPs provide first-line treatment for such conditions.

PCPs receive consultation from a behavioral health expert such as a psychologist or psychiatrist who is usually off-site.

PCPs are supported by a BHC who may meet with the patient for one to five sessions to provide assessment, education, crisis intervention, or brief/focused behavioral counseling.

PCPs receive more extensive support from a team that provides evidence-based CC. The team usually includes a trained behavioral health care manager and a psychiatric consultant who helps with patients who have more persistent mental health and substance use problems. This moves care from an acute care to more of a chronic care model, applying well-established principles of population-based chronic illness care.

Patients who do not improve with primary care–based interventions or who request referral to specialty care are referred to specialty mental health providers. Primary care practices continue to provide the patient’s primary care and coordinate closely with the behavioral specialists. Patients whose mental health or substance use problems have improved in specialty care may be referred back for ongoing care to their PCP.

Such a stepped approach that involves a team of providers requires close communication and effective hand-offs. It has the best chance of success when we apply two principles of care: (1) measurement-based treatment to target and (2) population-based care.

Treatment to target requires providers to systematically track patient improvement and to adjust treatments if patients are not improving as expected. Clinical improvement is measured by validated measures of core symptoms such as the PHQ-9 for depression as well as individualized treatment goals.

Population-based care involves a commitment to tracking an entire population of patients so that patients don’t fall through the cracks. It is too easy for us as clinicians to focus only on the “numerator,” the patients who present in our waiting rooms for care. We often lose track of the “denominator,” those patients who need care and who are not yet recognized and engaged in care, or those who have initiated care but are falling through the cracks because of inadequate follow-up.

A stepped approach to integrating behavioral health care, along with a commitment to the principles of treatment to target and population-based care, offers us the best chance of achieving the Triple Aim of health care reform: improving access to care, improving health outcomes, and making the most cost-effective use of our existing health care workforce. In such a stepped care approach, psychologists are ideally positioned to support PCPs with diagnostic assessments and with brief counseling or longer-term evidence-based psychosocial interventions. Psychiatric consultants can help with complex differential diagnoses that require a solid understanding of medicine and the medical causes of psychiatric symptoms. They can also support complex pharmacological management, often in patients who are already taking medications for acute and chronic medical problems. Nurses, social workers, and other health care professionals can provide much-needed care management, facilitate effective communication and collaboration between all team members, support the use of evidence-based psychotherapy and medication management, and make sure that patients don’t fall through the cracks. In the recently published book Integrated Care: Creating Effective Mental and Primary Health Care Teams, we outline how the various members of a collaborative care team can work together to treat patients with a range of common behavioral health problems in primary care.

More than half of those living with mental health or substance use problems in the United States do not receive any professional care, and most counties have shortages of mental health professionals. APA has recently committed to training 3,500 psychiatrists in integrated care through its Transforming Clinical Practice Initiative, but there are important roles for all behavioral health professionals in integrated care. We will need “all hands on deck” to improve access to mental health care for all. ■