Tips for Reducing Suicide Risk When Prescribing Hypnotics

Abstract

Studies of suicides that occur among patients using prescription sleep aids are often unable to disentangle the confounding factors of mental illness and substance use disorders.

Petros Levounis, M.D., says that in treating insomnia, he first educates patients about sleep hygiene and tries some basic cognitive-behavioral interventions before prescribing sleeping aids.

Hypnotic medications are associated with suicidality, but the association may often be confounded by the presence of mental illness, or the use of alcohol or other substances, according to a review that appeared last month in AJP in Advance.

Although hypnotic-associated suicide can occur in patients without a history of a mental illness and in the absence of substance use, it appears to be very rare. Most importantly, these rare, idiosyncratic reactions occur specifically at times of peak drug effect, during a period of confusion, amnesia, hallucination, or paranoia in the first few hours after ingestion of a hypnotic. Experts believe that judicious prescription and use of hypnotic medications may be able to help mitigate the risk of these events.

The review, led by W. Vaughn McCall, M.D., M.S., focused on modern, FDA-approved hypnotics, beginning with the introduction of benzodiazepines, and was limited to adults 18 years and older. McCall and colleagues searched PubMed and Web of Science, crossing the terms “suicide” and “suicidal” with each of the hypnotics. The FDA website was searched for postmarketing safety reviews, and the FDA was contacted with requests to provide detailed case reports for hypnotic-related suicide deaths reported through its Adverse Event Reporting System.

The portrait that emerged from the review is a complicated one, said McCall, chair of the Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior at the Medical College of Georgia. He told Psychiatric News that he began looking into the subject of hypnotics and suicide after black-box warnings were added to hypnotics alerting clinicians and patients to a risk of suicide.

“This gives the impression they are dangerous, but it has been my hope that by treating insomnia, we might be doing the opposite and diminishing the risk of suicide,” he said.

McCall said one of the surprising findings from the review was that there are rare case reports of people who have an idiosyncratic reaction to the hypnotic and become suicidal. Such cases are “extremely rare—maybe one in a million—but there are these rare paradoxical reactions,” he said.

“The caveat to this is that when one of these rare idiosyncratic reactions happen, they occur in the first few days of the prescription,” McCall continued. “It’s not likely to happen with a patient who has been using the sleep aid for a long time. But for the first-time user, the first several days should be considered a risk period.”

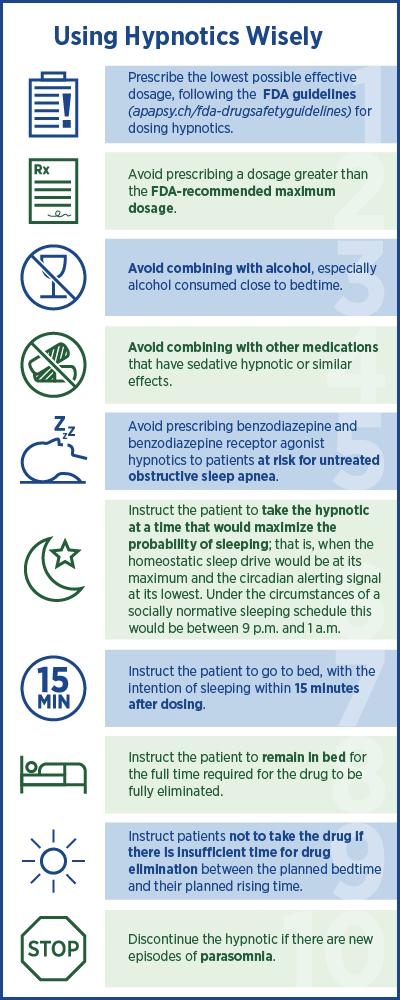

To reduce the risk of suicide when prescribing hypnotic medications, the authors offer a list of 10 recommendations for safe prescribing that focuses on thoughtful prescribing and careful instructions to patients about when and how to use hypnotics (see left).

Outside of these idiosyncratic case reports, the association of hypnotic use and suicide becomes complicated by the presence of mental illness and/or the frequent concomitant use of alcohol or other substances.

“[B]ecause of the confounding factors in epidemiologic studies of diagnosis and treatment for mental illness, it really wasn’t clear that it was the pill that was causing the suicide,” McCall said. “This leaves open the possibility that in the vast majority of patients, treating for insomnia is likely to move them further away from suicide.”

Petros Levounis, M.D., a consultant to the APA Council on Addiction Psychiatry who reviewed the report for Psychiatric News, said benzodiazepines and other hypnotics certainly have an abuse potential on their own, and patients with or without comorbid mental illness may become fully addicted to them. Levounis is a member of the Psychiatric News PsychoPharm editorial board.

“As an addiction psychiatrist, I also see patients who use hypnotics in combination with other CNS depressants, such as alcohol and opioids—both prescription narcotics and heroin,” he told Psychiatric News. “The synergistic effect of using multiple drugs from different classes, all of whom depress the respiratory system, increases dramatically the lethality of an accidental overdose or an intentional suicide attempt.”

Levounis said that when treating insomnia, he first educates the patient about sleep hygiene, offers some basic cognitive-behavioral interventions, and “tweaks” their psychopharmacological regimens before moving to sleeping aids. Common cognitive-behavioral interventions for insomnia include stimulus control—setting a consistent bedtime and wake time, avoiding naps, using the bed only for sleep and sex—and coaching about lifestyle changes, such as not smoking or drinking coffee late in the day.

When prescribing sleep aids to patients with substance use disorders, Levounis recommends ramelteon and low doses of the “z-drugs” (zolpidem, zaleplon, and es-zopiclone), which he said “seem to be somewhat safer choices” for this group.

Levounis called the 10 recommendations developed by McCall and colleagues “excellent” and said he hopes they get disseminated widely. “Responsible opioid prescribing and responsible hypnotic prescribing should be the cornerstones of our work when it comes to using medications with a significant addictive potential,” he said.

In the interview with Psychiatric News, McCall emphasized common sense instructions for patients about how to use prescription sleep aids. “The most practical way to prevent the patient from having one of these idiosyncratic reactions is to take the pill in a manner that leads to sleep rather than intoxication,” he said. “If you take the medication when you are wide awake in the middle of the day, it may not put you to sleep but intoxicate you and put you at risk.

“You really should only take a pill at a time of day when you have a chance of sleeping. Some of the suicide reports described people who took the pill with only four hours remaining in bed so they got up intoxicated.”

McCall also advised clinicians to pay attention to that early risk period in a first-time user of hypnotics.

“If the patient comes back after being prescribed and admits to having odd behavior or symptoms, that’s probably enough evidence to stop the medication,” he said. “Given that these idiosyncratic reactions typically occur in the first week, patients should be seen back in seven to 10 days. Previously in my own practice, I might have given a one-month supply. Now I’m rethinking that.”

The review was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention. ■