Tell It Like It Is

However, keeping in mind my being a good psychiatrist, I didn’t answer but said, “Why do you ask?”

He explained to me what a nice woman Tony Soprano’s psychiatrist was and how, when Tony’s wife became very upset, she sent the wife to another psychiatrist, this one male and Jewish. The latter psychiatrist had, in contrast, been “very blunt,” my patient said, and seemed to tell her that if she stayed with Tony, that was the treatment she could expect from her husband. She didn’t like what the second psychiatrist had said, so her regular psychiatrist said at least she couldn’t say she hadn’t been told.

It surely looked like my patient was referring to me, also a man and Jewish. We had had a similar discussion in the previous session relating to a rather difficult girlfriend of the patient’s. Coincidentally, the next day my 8 a.m. patient came in with the same comment about “The Sopranos.” We too had had such a discussion earlier, for he was in a similar situation at work. It definitely made me think.

I realized then that another reason I did not like “The Sopranos” was that I had felt strongly that there was an incorrect use of psychiatry going on there and, unfortunately, not an uncommon one. I had not liked Tony’s “nice” psychiatrist giving him “psychotherapy” while he was busy hijacking trucks, murdering people, and all the other things gangsters do. She was silent about the here and now, and silence is assent, for that’s the way it’s usually interpreted. No matter what they were talking about, the message she was sending was that it was all right for him to go on doing what he was doing, gangstering away.

In contrast, the male psychiatrist had spoken clearly and realistically to Tony’s wife about her life situation and its consequences and was not just passively accepting it and giving permission for it to go on. He would clarify it, and the rest was up to her.

I believe we psychiatrists should not let our understanding of pathology get in the way of our seeing what the person is doing in reality with that pathology, regardless of whether that pathology is biological, psychodynamic, sociological, or all of the above. Unless the person is so ill or retarded as to be decisionally incapable, there is still a person inside somewhere, making choices. Influenced by pathology, yes. Helpless? That is the question.

One sees this, unfortunately not so infrequently, with addiction, where psychiatrists may be unaware, not searching for, minimizing, or overlooking the reality of the addiction’s role in the picture. In those instances, one sees talking and meds but no attention being paid to the alcohol or drugs that are producing much of the problem and whose use continues despite the talk and meds. It may well be that this could account for some of our bad press in some parts of the addiction community.

The same situation holds true regarding other life stresses that can be medicalized or psychologicalized: intolerable work situations, impossible interpersonal relations, abuse, poverty, oppression, and inadequate health care, for example. Psychiatry is for psychiatric illness; it is not to encourage submission to the miseries that life might impose on us unless there is absolutely no other way.

We psychiatrists must orient ourselves toward trying to help people face challenges, to help them change as much as possible. Our psychiatric treatment is directed against those forces and tendencies within them that interfere with their doing so.

I think if I were examining Tony Soprano’s psychiatrist for the boards, I would flunk her. ▪

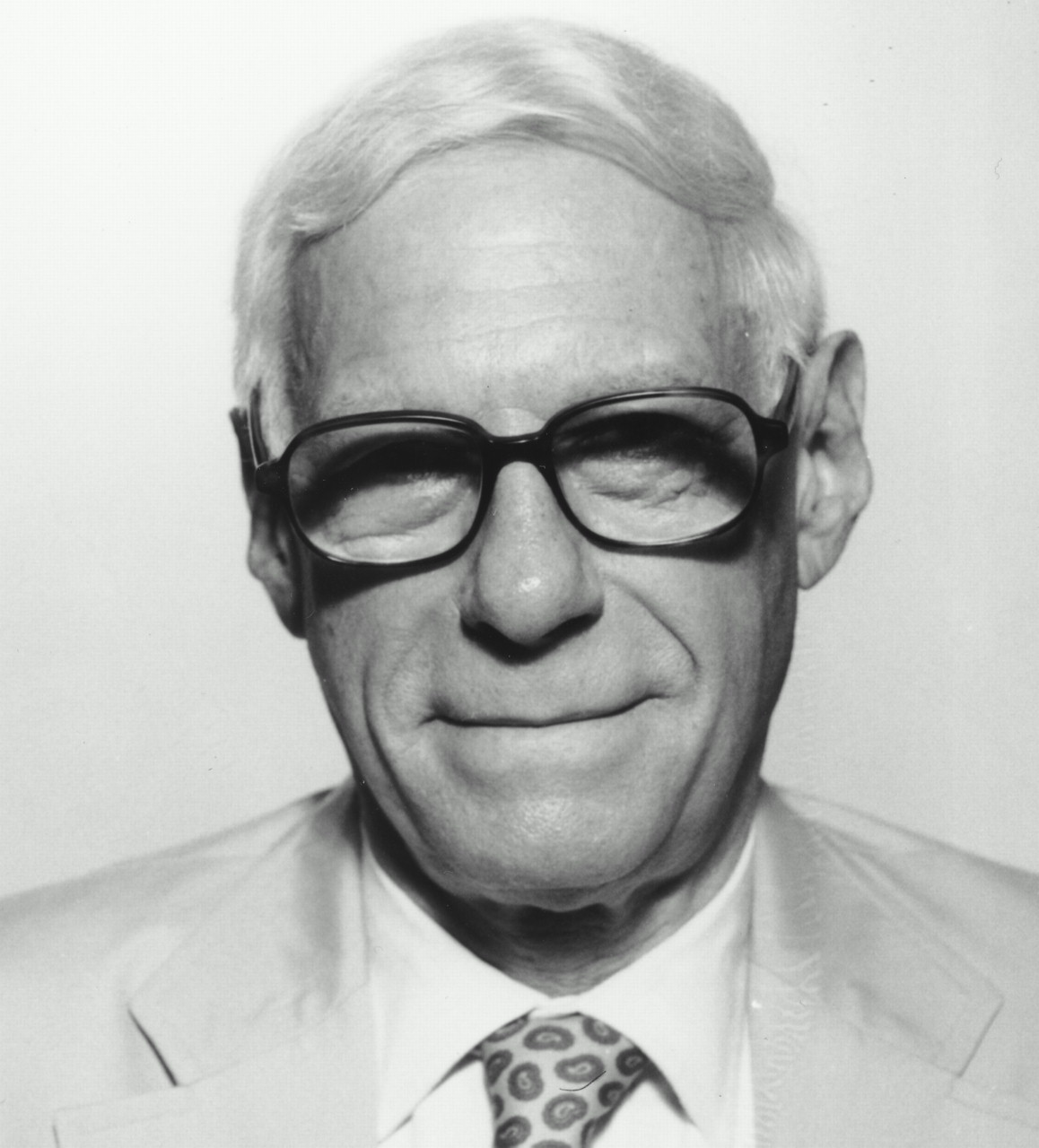

Dr. Peyser is a psychiatrist in private practice in New York and the Area 2 representative on the APA Board of Trustees.