New Mexico Governor Signs Nation’s Only Psychologist-Prescribing Law

With the signature of Gov. Gary Johnson (R) on the evening of March 5, clinical psychologists in the largely rural southwestern state of New Mexico became the first in the nation to be legally eligible to qualify to prescribe psychotropic medications to patients with mental illnesses.

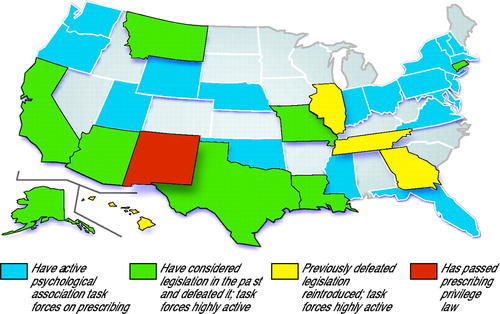

Four other states—Georgia, Tennessee, Illinois, and Hawaii—have reintroduced previously defeated legislation granting prescribing privileges to psychologists. And that is only the beginning. To date, eight other states have introduced, but defeated, similar legislation. According to the American Psychological Association, 31 state psychological associations currently have prescription-privilege task forces actively lobbying their state legislatures (see map).

Four other states—Georgia, Tennessee, Illinois, and Hawaii—have reintroduced previously defeated legislation granting prescribing privileges to psychologists. And that is only the beginning. To date, eight other states have introduced, but defeated, similar legislation. According to the American Psychological Association, 31 state psychological associations currently have prescription-privilege task forces actively lobbying their state legislatures (see map).

APA President Richard Harding, M.D., issued a statement March 6 deploring the decision of the New Mexico legislature and the governor to enact the precedent-setting legislation.

“The new law,” Harding said, “is the result of a cynical, economically motivated effort by some elements of organized psychology to achieve legislated prescriptive authority without benefit of medical education and training.” He emphasized that “psychology prescribing laws are bad medicine for patients.”

The governor’s signature capped a feverish few weeks of meetings and negotiations between legislators, the governor, and representatives of the Psychiatric Medical Association of New Mexico (PMANM), the New Mexico Medical Society (NMMS), and the state psychological association.

However, in spite of strong efforts by psychiatrists to inform the governor of concerns over patient safety, he seemed to base his decision on a controversial compromise negotiated during the last few days of the legislative session between NMMS and the psychological association. Amendments to the bill by these two groups centered on training requirements not supported by PMANM. Nonetheless, the amendments effectively killed efforts to defeat the legislation.

“What I found,” Gov. Johnson told Psychiatric News, “and we had several meetings about this over a period of time, but what I found was that no one that I talked with objected to psychologists being given the right to prescribe drugs, as long as they received the proper training. And so from [the psychiatrists], that would only be proper medical school training.

“Our law will require the board of medical examiners and the board of psychology to get together and hammer out exactly what the proper training is. I am confident that they’ll come up with a training program that is satisfactory to both sides and that will ensure the safety and welfare of New Mexico’s citizens, while at the same time expanding availability and access of these medications to the patients who need them.”

Several factors appear to have been of primary influence in the passage and signing of the law. High on the list of both the New Mexico legislature and the governor, according to numerous sources, was concern over what they see as a critical need for expanding rural access to mental health care.

“There is an absolute need for increased psychiatric care in this state,” said Diane Kinderwater, the governor’s director of communications. “And that was obviously a factor in [the governor’s] decision.”

According to the New Mexico Board of Medical Examiners and the AMA’s Physician Masterfile, there are between 225 and 250 psychiatrists practicing within the state of 1.8 million residents. Only about 60 of those, or 24 percent, however, practice in the vast expanses of largely rural areas outside Albuquerque and Santa Fe. Census data indicated in 2000 that 61 percent of the total population in the state lives outside those metropolitan areas.

“We all know that there is a crisis in access to mental health care in rural areas,” Gail Thaler, M.D., president of PMANM, told Psychiatric News. “But the real data are very difficult to actually get.”

Gauging Rural Access

The New Mexico Department of Mental Health estimated in its report, “State of Health in New Mexico: 2000,” that just under 80,000 adults in the state suffer from a “serious mental illness.” In addition, some 45,000 residents under the age of 18 have a “serious emotional disturbance. . .that seriously interferes with the child’s role or functioning in family, school, or community activities.” If the raw estimates are close to reality, there would be, on average, 500 seriously ill patients for each psychiatrist in the state.

The state report noted “many serious barriers” to access to mental health care in the state, most notably poverty, lack of health insurance, and lack of availability of care in rural settings.

The report strongly suggested collaboration between the Department of Health, the University of New Mexico, and New Mexico State University to develop ways to improve rural access to care. Thaler told Psychiatric News that those efforts are now under way. “But in terms of regular acute [nonemergency] access, that’s not really adequately covered in many communities.”

Albert Vogel, M.D., associate dean for clinical affairs at the University of New Mexico, is APA’s Area 7 Trustee. Vogel told Psychiatric News that rural access is a concern throughout Area 7 and that the issue was heavily pushed by lobbyists for New Mexico’s state psychological association.

The New Mexico Psychological Association’s lobbyists tried to use the argument that expanding psychologists’ scope of practice to include prescribing would result in an increase in available care.

“Clearly, that is a specious argument,” Vogel said. PMANM conducted an informal survey throughout the state and found only one or two counties that were served by a psychologist that were not served by a psychiatrist. Both Vogel and Thaler cited studies in California that have shown that psychologists are no more likely to locate in rural areas than are psychiatrists.

However, one argument used by the psychological association, and reportedly confirmed by many rural nonpsychiatric physicians, resonated loudly with the governor, according to Kinderwater.

“They said that ‘You know, psychologists are already out there recommending to primary care physicians what medications to prescribe for which patients,’ ” said Neil Arnet, M.D., immediate past president of PMANM. And the lobbyists argued that it would be more efficient from both a time and cost standpoint to simply have one person provide counseling and medication.

Arnet was actively involved, along with PMANM legislative representative George Greer, M.D., in the district branch’s efforts to defeat the assertions and attended meetings where lobbyists used that argument.

“The governor saw the bill as simply removing a layer of bureaucracy from the process of getting the medications to the patients,” Arnet told Psychiatric News. “It was a very effective argument.”

Allan Haynes Jr., M.D., president of NMMS agreed. “The reality in our state,” he told Psychiatric News, “is that we are extremely short [of qualified mental health clinicians]. Now, I am a urologist, but I’ve had some of the clinical psychologists call me, on occasions when I’ve been the only physician readily available, and say, ‘Well, I’ve got so and so here, and he’s going through this type of problem. Many years ago he was a patient of yours, and so would you mind prescribing drug X?’

“Is that good medicine?,” Haynes asked, “No. But what do you do? People would rather take some medicine than get nothing at all. That is what we’ve been doing.”

So, Haynes stressed, many rural physicians who already have an ongoing relationship with a clinical psychologist do not see granting them prescribing privileges as any threat professionally or from a patient-safety standpoint.

Brokering Amendments

Haynes said that this general lack of apprehension led the executive council of the state medical society to reassess the chances of the bill’s being defeated.

The version of the bill that had passed the state House a year ago and was defeated only by time running out in the Senate was reintroduced in January. That version, HB 170, had less stringent educational requirements, lacked any physician oversight of psychologists’ prescribing, and had no provision for the two-year “conditional” period contained in the final version of the new law.

“We were faced with something,” Haynes told Psychiatric News, “that would send these people out after 18 weeks of Saturday afternoon classes and be able to prescribe.”

In addition, Haynes said, early in the session, “I had senators and representatives saying to me, ‘I haven’t had any phone calls about it. So if it is such a really bad idea, why haven’t I been hearing from people?’ That pretty much made it impossible to argue with.”

Haynes said NMMS had to try to do something to “improve the odds for patient safety.”

Little Time Left

Because the legislative session was mandated to last only 30 days, and the governor had decided only at the last minute to add the bill to his legislative agenda for the session. PMANM and NMMS had very little time to rally their opposition to the bill.

PMANM, with assistance from APA’s Division of Government Relations, offered several amendments, including a requirement that all psychologist prescribing be under the direct supervision of a physician, similar to the relationship of physician assistants in many states. PMANM also tried to put forward an amendment that would have restricted a psychologist’s prescribing to the rural areas that the psychologists were arguing so badly needed the increase in providers. These proposed amendments were made to the House Judiciary Committee but hit a dead end because of subsequent developments.

PMANM, Arnet told Psychiatric News, backed the introduction of an alternative bill, HB 305, which was modeled after the state law governing prescribing by clinical pharmacists. This law allows limited prescribing under strict supervision after educational requirements are met.

Just when Arnet thought HB 305 was going to be introduced, Haynes told Arnet that he was meeting with the other side to work on a compromise version of the reintroduced HB 170. “I told him that we would not support any compromise,” Arnet told Psychiatric News.

At this point, Haynes said he believed that the legislature was prepared to pass HB 170 and send it unamended to the governor for his consideration. NMMS was not confident there was much chance for securing a veto.

On Friday, January 25, the state conference committee considering HB 170 tabled the issue until the following week, expressly to allow the alternative bill to be introduced the following Monday. That Saturday, House Judiciary Chair Ken Martinez called a meeting with Haynes and a representative of the psychological association, and, indeed, they brokered a compromise.

All the psychologists wanted was independent prescribing, Haynes and Arnet told Psychiatric News. They did not appear to be as concerned about how it was achieved. Haynes offered to accept independent privileges only if the psychologists accepted strengthened educational requirements, a two-year conditional period of strict oversight, and overall oversight by the state board of medical examiners and the board of psychology. The final language of the law sets minimum educational requirements; however, it calls on both the boards of medical examiners and psychology to work out the final acceptable requirements (Original article: see box).

The psychologists agreed, Arnet speculated, because they must have had some indication that the original HB 170, with its less-stringent educational requirements and oversight, was not as much a “done deal” as was being said by both legislators and the governor’s office.

“Once [Haynes] negotiated,” Arnet said, “the political leverage was lost, and that effectively defeated psychiatry’s efforts to kill the bill.”

PMANM President Gail Thaler agreed. “When the board of medical examiners was added to the bill, it was sort of the death knell for us in terms of getting the whole thing stopped,” she told Psychiatric News. “It looked like an endorsement. And I must say, it certainly is better with the amendments than without them.”

Arnet believes NMMS’s Haynes did what he thought was best under difficult political pressure. “He absolutely wanted to have board [of medical examiner] oversight in the law,” Arnet said, “and he got what he wanted when he gave [psychologists] independence after two years.”

Both Thaler and Arnet are concerned, however, about vague language in the law regarding the “dual oversight” provisions. For example, the law does not say what will happen if the two boards are not able to agree on the educational requirements they have been entrusted to develop. No provisions exist for resolving any disagreement, which most believe is inevitable.

The Battle Ahead

In an e-mail to members on APA’s e-mail distribution lists, APA President Richard Harding, M.D., Medical Director Steven Mirin, M.D., and Director of Government Relations Jay Cutler, J.D., detailed their summary of “the major lessons learned from this battle” and outlined what APA needs to do to “be prepared for a newly energized push” for prescribing laws in other states (see Original article: page 3).

Those involved in the New Mexico battle say they have learned valuable lessons that could help in the battles sure to be fought in other states. “We must be more proactive,” Arnet said. “Whatever it takes to get in and do personal meetings with the legislators, you have to do it.” Letters and phone calls are helpful, he added, but not as effective as a one-on-one meeting.

Both Vogel and Thaler agreed. “You’ve got to find out what is happening in your state legislature and start very, very early with vigorous lobbying,” Thaler said.

Arnet told Psychiatric News that combating misinformation is also a key. “The psychologists hired a telephone-survey company to find out how many psychiatrists were in the state. And if you didn’t get called, I guess they didn’t count you.”

A press release issued by the American Psychological Association, announcing the bill’s signing, claimed that “there are only 18 psychiatrists serving the 72 percent of New Mexicans who live outside Albuquerque and Santa Fe.” The group also claimed there were only around 90 psychiatrists in the state. The numbers are clearly inaccurate based on data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the New Mexico Board of Medical Examiners, and the AMA Physician Masterfile. “Distortions must be dealt with immediately and vigorously,” Arnet said. “The longer they hang around, the more ‘true’ they appear to be.”

PMANM members are still feeling stung by the defeat, Thaler and Arnet said. But both agreed that they will do everything possible to ensure the safety of the state’s patients. On the battle, Arnet said, “I hope that this will act as a wake-up call.”

The text of the New Mexico law can be accessed on the Web www.legis.state.nm.us by entering “170” in the “Bill Finder” box on the left. The report “State of Health in New Mexico: 2000” is posted at www.health.state.nm.us/StateofNM2000. ▪