Scientists Home In on Link Between Anxiety, Alcohol Use

It is well known that alcohol acts as a general anxioloytic and that anxiety and alcohol dependence frequently occur together. But the effect of alcohol on anxiety has been difficult to pin down clinically, and reports in the literature of this comorbidity are unclear about how and in whom it occurs.

Now scientists have identified a central amygdaloid signaling pathway involved in anxiety-like and alcohol-drinking behavior in rats that sheds light on the regulation of these two behaviors.

Subhash Pandey, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry and director of neuroscience and alcoholism research at the University of Illinois, and colleagues in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Illinois and at the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center in Chicago found that rats bred to prefer alcohol (P) showed more anxiety-like behavior and drank more than rats with no preference for alcohol (NP).

A report of his study, which was funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), appears in the October 3 Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Anxiety-like behavior was measured using a maze with open and closed arms: the greater the “anxiety” level the longer time rats spent in the closed arms.

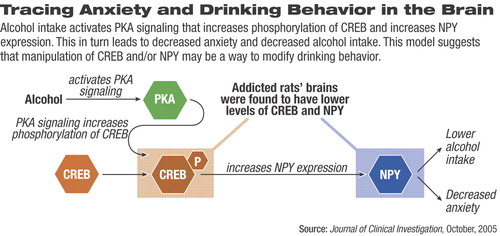

Analysis of the rats' brains revealed that addicted rats had lower levels of cAMP responsive element-binding protein (CREB) than NPY rats did. CREB or cAMP in the central amygdala is associated with high anxiety and alcohol-drinking behaviors. Also, levels of neuropeptide NPY were lower in addicted rats. NPY regulates several neurotransmitters and plays a role in anxiety and alcohol-drinking behaviors.

The coupling of CREB and NPY regulates NPY production.

More remarkably, drinking reduced anxiety-like behavior in addicted rats, an effect associated with increased CREB function and NPY production. In addition, administering compounds that promote CREB function and NPY production also reduced anxiety and drinking in addicted rats.

More significantly, disrupting CREB function and NPY production in NP rats provoked anxiety-like behavior and promoted drinking.

This is the first direct evidence that a hereditary deficiency of the CREB protein is associated with high anxiety and drinking behaviors. Genetically, high anxiety levels are important in the promotion of higher alcohol consumption in humans, and drinking is a way for anxious people to self-medicate.

Pandey and his colleagues proposed that in nonaddicted rats, decreased CREB-dependent NPY production might be a preexisting condition for anxiety and alcohol-drinking behaviors.

“These experiments, conducted in rats selectively bred to have a high affinity for alcohol, help us address questions about the potential role that anxiety might play in human alcoholism,” said NIAAA Director Ting-Kai Li, M.D. “They may reveal potential targets for therapy of anxiety and alcoholism.”

Psychiatric News asked addiction-research experts for their reactions to the findings.

“Some individuals may drink to relieve preexisting stress, and this study suggests that innately lower levels of CREB in parts of the amygdala may identify these individuals,” said Sarah Book, M.D., an assistant professor of psychiatry at the Charleston Alcohol Research Center of the Medical University of South Carolina.

“Drug development can then target an at-risk population of individuals with an anxiety disorder who drink to cope with their anxiety. Identification of at-risk populations who drink because alcohol 'normalizes' an underlying anxiety disorder is a fruitful research area,” she said.

Book said that in future work it would be important to see if similar results are seen in this and in other animal models of anxiety. Her group, as well as others, have proposed that using alcohol to ameliorate a negative sensation such as anxiety (negative reinforcement) may explain why some individuals with anxiety disorders develop alcohol dependence comorbid with their preexisting anxiety disorder.

In a related commentary in the journal Gary Wand, M.D., wrote, “These provocative data suggest that a CREB-dependent neuromechanism underlies high anxiety-like and excessive alcohol-drinking behavior.” Wand is a professor of medicine and psychiatry and director of the Endocrine Training Program at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine.

He said that the data need to be replicated and then placed in context with two other important neurotransmitter systems in the amygdala: corticotropin-releasing factor-mediated (CRF-mediated) and GABA-mediated signaling.

“This is an outstanding finding and very interesting,” commented George Koob, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and psychology at the University of California at San Diego and director of the Division of Psychopharmacology at Scripps Research Institute.

But Koob believes that Pandey has only one piece of the picture. Along with Wand, Koob believes another factor that needs to be investigated is CRF, which plays a role in the brain's ability to manage an internal response to daily stressful situations.

“CRF is just the opposite of NPY,” he explained. “When NPY goes down, CRF goes up, and vice versa. And we find that CRF antagonists have some of the effects [Pandey] sees when he increases NPY.”

While all the experts interviewed praised the study, some questioned the pros and cons of extrapolating results in animal models to human behavior.

“Although the brain structures and the molecular events described may help to understand human neurobiology, the capacity to model human drinking behavior or alcohol's effects in humans through the use of rodent models is limited,” cautioned Henry Kranzler, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and assistant dean for clinical research at the University of Connecticut School of Medicine.

For example, although the role of NPY is well established in feeding and drinking behavior in rodents, Kranzler said the literature on its role in human drinking behavior is much less clear. “Similarly, the modeling of anxiety in rodents is limited, so the complex relations of anxiety and drinking behavior in humans are, in my view, not adequately modeled in rodents,” he added.

“I think this is very exciting research, and it illuminates a potential mechanism for one of the ways genetics may influence the likelihood of alcoholism dependence,” said Mark. Willenbring, M.D., director of NIAAA's Division of Treatment and Recovery Research.

“There are multiple pathways to developing dependence and this may be one of them. It certainly fits clinically, and there is a strong relationship between anxiety disorders and heavy drinking,” he said.

He explained that what is called “anxiety behavior” in animal models is an inference, and researchers still do not know very much about how that happens in humans. This is one of the limitations of using animal models.

“Deficits in Amygdaloid cAMP-Responsive Element-Binding Protein Signaling Play a Role in Genetic Predisposition to Anxiety and Alcoholism” can be accessed at<www.jci.org/cgi/search?fulltext=pandey&journalcode=jci> by clicking on the article title. ▪