Children of Depressed Parents Have More Health Problems

The adult offspring of depressed parents are far more likely than those of nondepressed parents to have a host of psychiatric and medical problems, such as cardiovascular disease, according to a study reported in the June American Journal of Psychiatry.

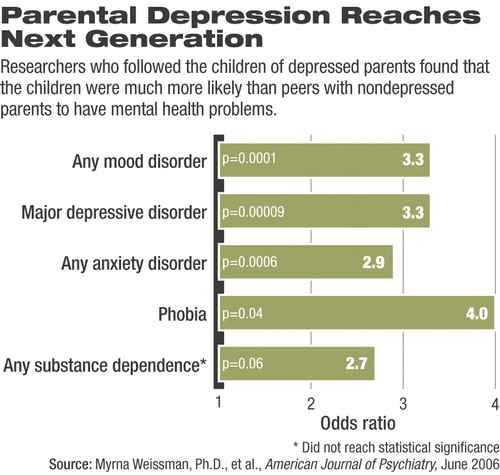

The study found that the rates of anxiety disorders, major depression, and substance use disorders were about three times that of offspring from nondepressed parents 20 years after a baseline survey.

In addition, adult children of depressed parents had about five times the rate of cardiovascular illness as children of nondepressed parents.

“Based on these findings, the children of depressed parents have high rates of depression and anxiety disorders that are impairing and reoccur over the course of their lives,” lead author and study investigator Myrna Weissman, Ph.D., told Psychiatric News.

Weissman is a professor of epidemiology in psychiatry at the College of Physicians and Surgeons and the School of Public Health at Columbia University.

Weissman first began following her sample of 151 children from depressed and nondepressed parents in 1982 in their homes in New Haven, Conn.

Some of her sample were drawn from the offspring of depressed adults receiving outpatient depression treatment at Yale University's depression research unit in the early 1980s. The adults who volunteered their children to be studied were moderately to severely depressed, Weissman said.

She also recruited children of nondepressed parents who participated in the Epidemiologic Catchment Area study.

She assessed 220 offspring aged 6 to 23 in both groups at baseline and then at two years, 10 years, and 20 years later.

By the 20-year follow-up evaluation, there were 101 offspring with one or more parents with depression and 50 offspring with parents with no depression.

To screen the offspring, researchers used the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia-Lifetime Version, the Global Assessment Scale, and the Social Adjustment Scale-Self Report. Researchers also used a standard medical checklist to gather information on nonpsychiatric medical conditions.

Twenty years after she first studied them, Weissman found that the offspring of depressed parents had higher rates of major depression over the two decades (65 percent) compared with offspring of nondepressed parents (27 percent) in her sample.

Compared with their peers, children of depressed parents had about three times the risk of developing depression by the time they were adults.

In addition, while just 15 percent of offspring of nondepressed parents had a phobia, 43 percent of offspring of depressed parents did, which meant they had three times the risk for developing a phobia by the time they were adults.

The study noted that “peak of first onset [of psychiatric disorders] was before the age of 20, with anxiety disorders before puberty and with major depression and substance dependence after puberty.”

Twice as many of the offspring of depressed parents (19 percent) developed an addiction to drugs or alcohol, as did those of nondepressed parents (8 percent), putting them at more than twice the risk of developing a substance use disorder.

Offspring of depressed parents also had more medical problems than their counterparts.

Weissman found that by the 20-year evaluation, 11 percent of offspring of depressed parents had developed cardiovascular disease, compared with only 2 percent of children of nondepressed parents, making the former about five times as likely to develop heart problems as adults.

Offspring of depressed parents were also more than twice as likely to develop a neuromuscular disorder.

Weissman cited a number of studies that have found an association between depression and cardiovascular illness and said that an association between the two conditions could stem from altered immune, platelet, and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning in depressed patients.

She said that neither parents nor children with depression should be considered in isolation of one another.

“If clinicians see a child with a psychiatric illness, they should examine the parents and see if one or both are depressed,” Weissman said, and do the same for depressed adult patients who have children.“ Parents and children should be considered a package.”

Weissman is now evaluating a subsample of the children of the offspring she studied to determine the specific factors that may contribute to their mental health problems.

An abstract of “Offspring of Depressed Parents: 20 Years Later” is posted at<http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/> under the June issue. ▪