Follow-Up Care Often Lacking In Depression Treatment

Adults and children who began a new course of antidepressant therapy before the appearance of black-box warnings pertaining to SSRIs' risk of suicidality received far less follow-up monitoring than is recommended by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

That was the finding from a study following a cohort of more than 84,000 patients in a large managed care organization for 12 weeks. The findings appeared in the august American Journal of Managed Care.

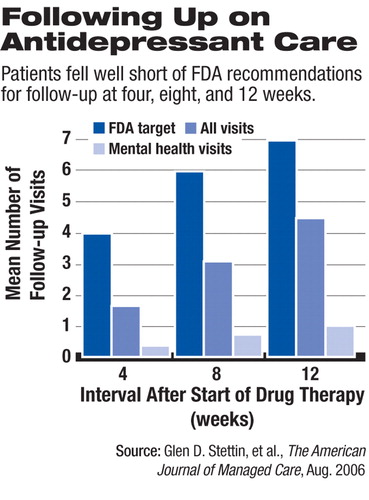

The study is a retrospective examination of practice patterns in a commercial population before the FDA held hearings and subsequently issued black-box warnings regarding risk of suicidality with SSRIs. The new warning labels recommend at least seven visits during the first 12 weeks of treatment: weekly visits during the first four weeks, visits every other week during the next four weeks, and a visit during the 12th week.

The results of the study appear to underscore in a general way the poor rate of follow-up care for patients receiving antidepressant therapy.“ The results of our study suggest that follow-up care in practice is far less frequent than what is recommended by the current product labeling,” wrote Glen Stetin, M.D., and colleagues. “in this study sample, more than 80 percent of patients had no mental health visits with health care providers during the first four weeks after starting antidepressant therapy, and the average patient had only one or two face-to-face visits for any purpose during that period.”

Stein is with Medco Health Solutions Inc., a pharmacy benefits management company that manages prescription benefits for the population that was studied. Drug-utilization data for the study were drawn from a prescription claims database maintained by Medco. Medical utilization data, including mental health care claims data, were drawn from an administrative claims database maintained by the managed care organization.

Experts who reviewed the study, and the authors themselves, said it provides only the roughest kind of approximation of what is happening to patients who are prescribed antidepressants. Moreover, it remains unknown what the optimal cost-effective level of follow-up care is; the target of seven visits in 12 weeks is an arbitrary figure, which, if followed consistently by clinicians and patients, would substantially increase costs.

“It is clear from the results of this study that improvements are needed in the timing and frequency of follow-up care for patients who start antidepressant therapy,” said Stetin and colleagues. “However, it is difficult to define what level of follow-up care is a cost-effective and clinically appropriate target for health care providers... .If increased visit frequency translates into improved recovery rates, the increased costs of follow-up care may be offset by reductions in other direct costs, such as hospitalization or by reductions in indirect costs, such as absenteeism. In the absence of solid research data, these linkages remain speculative.”

Customize Each Monitoring Plan

A monitoring system tailored to the needs of each patient is what is needed, according to Darrel Regier, M.D., M.P.H., director of APA's Division of Research and the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education. Moreover, monitoring of patients has to include valid and reliable measurements of symptom severity, treatment response, and suicide risk, such as is provided by instruments like the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).

“We have argued all along that an arbitrary target of seven visits is not the way to go,” Regier told Psychiatric News. “One needs to have a way of monitoring that is more effective and tailor it to the patient. If you simply took an across-the-board recommendation that everyone has to have seven visits in 12 weeks, it would probably not be a cost-effective way to advance safety or efficacy.”

Antidepressant Prescribing Decreasing

Regier noted that there has been a significant decrease in the prescribing of antidepressant medication for children since the FDA black-box warnings were issued.

“The question is, given this drop in the rate of prescribing, has it resulted in a higher proportion of those receiving medications having the recommended visit rate? More important, what is the outcome in disability and suicide risk for those not receiving treatment because of this FDA requirement? and what is the treatment response and suicide risk reduction for those with an increased visit rate?

“If the entire health system devoted more visits out of its current capacity to monitoring antidepressant use in face-to-face visits instead of allowing some telephone contact, what other medical and psychiatric disorders would receive less treatment?” Regier asked.

Edward Gordon, M.D., chair of APA's Medicare Advisory Corresponding Committee, emphasized the role of managed care in restricting access to treatment for depression.

“One of the real problems with patients getting adequate care of depression is that their insurance coverage is inadequate,” he said.“ Very often it allows as few as 20 visits a year, including for the family and children, and the fees are so low that it has caused a real shortage of people to do the treatment.”

Gordon also criticized the report noting that it revealed nothing about the actual clinical outcome of depressed patients.

“The [FDA] recommendations are inadequate themselves,” he said.“ Patients need care depending on how sick they are. This study is done by a pharmaceutical [benefit] management company and is an entirely nonclinical report. It has nothing to do with whether patients get better.”

And Gordon added that he believes the cost of mental health care should go up, if appropriate insurance coverage is provided.

“If the insurance companies really wanted adequate treatment they would increase fees and availability of services,” he said.

The study included 84,514 adult and pediatric patients who started a new course of antidepressant therapy for any indication between July 2001 and September 2003. Patients were members of a large managed care organization in the north-eastern United States. Ambulatory visits during the first 12 weeks of treatment were identified using medical claims data. Outcome measures were time to first follow-up visit, frequency of follow-up visits, and percentage of patients receiving recommended levels of care.

During the first four weeks of antidepressant treatment, only 55.0 percent of patients saw a health care provider for any purpose, and only 17.7 percent saw a provider for mental health care. Ambulatory visits during the first four, eight, and 12 weeks were significantly lower than the minimum levels recommended in product labeling.

Only 14.9 percent of patients received the FDA-recommended level of follow-up care during the first four weeks, 18.1 percent at eight weeks, and 22.6 percent at 12 weeks, according to the study.

APA Trustee and child psychiatrist David Fassler, M.D., said the analysis does not distinguish between patients who received a prescription from a psychiatrist as opposed to a pediatrician, internist, or other primary care physician. Moreover, the database appears to encompass claims from all mental health care clinicians, Fassler said.

“Accordingly, there's no way to know whether the follow-up visits actually incorporated any clinically meaningful aspect of `monitoring,'” he said. “Nonmedical visits would also fall outside the parameters contained in the guidelines eventually issued by the FDA.”

“It is clear from the results of this study that improvements are needed in the timing and frequency of follow-up care for patients who start antidepressant therapy.”

Fassler observed that the results reveal little about current practice patterns with respect to follow-up for children, adolescents, and adults who are being treated with SSRIs.

“We have seen a reduction of over 20 percent in overall prescriptions of SSRIs for patients under the age of 18,” Fassler said. “In actual clinical practice, my impression is that most physicians are attempting to individualize the frequency of follow-up visits and phone contact to the clinical needs of the child and family.”

He added, however, that “it's clear that the specific schedule recommended by the FDA has not been widely adopted. As the authors of this article noted, the FDA guideline was not based on any specific data or study demonstrating improved outcome. Rather, it was adopted from a research protocol. The real issue isn't simply how many visits a child has; it's whether they're getting appropriate treatment that is based on a comprehensive evaluation and an accurate diagnosis.”

Fassler said that advocacy organizations such as Families for Depression Awareness have also developed “monitoring kits” for families to help them gather as much information as possible between office visits.

“In some parts of the country, child and adolescent psychiatrists are working with pediatricians and family practice physicians to develop local `standards of care' that are clinically based while also acknowledging regional variations with respect to access and utilization of limited resources,” he said.

“Frequency of Follow-up Care for Adult and Pediatric Patients During Initiation of Antidepressant Therapy” is posted at<www.ajmc.com/Article.cfm?Menu=1&ID=3169>.▪