Remission Possible, But Hard to Sustain

Findings from the latest phase of the National Institute of Mental Health's STAR*D (Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression) study indicate that patients who require multiple antidepressant drug trials to reach remission not only have significantly higher rates of relapse but also relapse sooner, compared with patients who require only one or two drug trials. Nonetheless, with persistence, about two-thirds of people with depression can reach remission if they are willing to try different medications.

This latest report, which appeared in the November American Journal of Psychiatry, is the 38th article on STAR*D published in peer-reviewed journals. It details the outcomes of the series of acute treatment steps that patients took to be well enough to progress to follow-up or maintenance treatment. Because the report connects acute treatment outcomes to longer-term prognosis in a well-characterized patient population of more than 3,600 patients, it may end up being one of the most important ever published on the treatment of major depression.

The STAR*D protocol consisted of a series of four randomized controlled treatment trials (each referred to as a “treatment step”) with outpatients who met DSM-IV criteria for nonpsychotic major depressive disorder. Remission was the goal of each step, defined as a score of less than or equal to 5 on the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self Report (QIDS-SR16) equivalent to a score of less than or equal to 7 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale. If patients did not achieve remission by the end of the 14-week step or could not tolerate a treatment step, they were encouraged to proceed to the next acute treatment step.

Those who achieved remission and tolerated their acute treatment could enter a 12-month naturalistic follow-up phase, as could those with “at least a meaningful improvement and acceptable tolerability.” During the follow-up phase, relapse was defined as a QIDS-SR16 of equal to or greater than 11.

The study was conducted at 41 clinical sites; 18 provided primary care, while 23 provide psychiatric care. The results of the successive treatment steps have been reported previously (Psychiatric News, January 20, April 21, July 7, September 15).

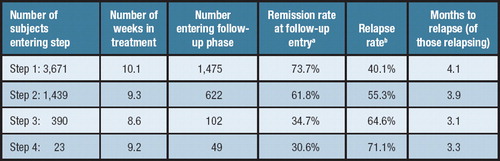

In the latest report, researchers consolidated an enormous amount of data on 3,671 patients who entered the protocol at the first step and their subsequent quest for remission through the four potential treatment steps.

All patients started the study in step 1, taking citalopram (Celexa). Those who did not do well on citalopram could progress to step 2, which involved either switching to a different antidepressant or augmenting citalopram with a second drug. For those who still were not well enough to enter follow-up, step 3 again offered a switch to a different antidepressant or augmentation of the patients' step 2 drug regimen. Step 4 offered a final opportunity to switch medications or augment a patients' step 3 regimen. Each of the individual steps in the protocol lasted for up to 14 weeks, and the follow-up phase of the study lasted for 12 months.

The STAR*D team found a couple of unexpected results that were“ counterintuitive,” said A. John Rush, M.D., in an interview. Rush is STAR*D's principal investigator and a professor of psychiatry and Distinguished Chair in Mental Health at the University of Texas–Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas.

“First, the proportion of patients who took multiple treatment steps was not really different between primary care sites and psychiatric sites—which is a very good finding. Most would have thought patients at psychiatric treatment sites would have fared better. Second, ethnic minorities have often been characterized as potentially more likely to leave treatment early, have higher levels of noncompliance, and higher levels of treatment-resistance. Again, we didn't find any significant differences between groups with different races or ethnicities [with respect to the average number of treatment steps taken to enter follow-up].”

Sicker Patients Need More Steps

“It's a sort of good-news, bad-news thing,” said Rush.“ This report can basically be broken down into three domains, each looking at a specific question: Who are the people who seem to require more treatment steps? What is the benefit achieved from multiple acute treatment steps? And what is the longer-term outlook in relation to different numbers of acute treatment steps?”

Regarding the first question, he continued, empirical data are now available that can help identify patients who may require more treatment steps to reach remission. Those data largely validate what clinicians and researchers have suspected for many years.

“We found that patients with more severe depression, greater general medical or psychiatric comorbidity, and chronicity made up the group that needed more treatment steps” to reach follow-up—either by achieving remission or at least a meaningful improvement with acceptable tolerability, Rush said. “So, the more problems you enter treatment with, the more steps you'll likely need.”

Moreover, Rush pointed out, the patients who took more steps to enter follow-up were significantly less likely to be in full remission when they entered the follow-up phase of their treatment, compared with the patients who took only one or two steps.

This finding shouldn't surprise anyone, said Rush, but it is the first time that it's been demonstrated in depression.

“With most patients who have other chronic medical disorders—for example, heart failure—you see the same decline in outlook. The tougher-to-treat patients take more treatment steps, and since they are tougher to treat, it is likely that outcomes will not be as good with later treatment steps.”

Treatment Length Matters

Another significant finding, Rush said, is the mean number of weeks patients remained in a treatment step (range: 8.6 to 10.1).

“These patients were treated for a significant period of time,” Rush said. “This wasn't a typical four- or six-week clinical trial. In addition, we were looking for remission, not just response.”

The study design was based on the principle that an adequate dose of a given medication needs to be tried for an adequate period of time in order to determine the drug's effectiveness, and the results validate this principle as a model for clinicians to follow. “otherwise,” Rush noted,“ you could be throwing away a treatment that the patient may have benefited from, just in the interest of time.”

Dosing of medications in STAR*D was flexible, but guided by a requirement to measure symptoms and side effects at each clinical visit. On the basis of those measurements, study physicians were strongly encouraged to increase the dose for a patient who had not achieved full benefit, as long as the patient was not experiencing any intolerable side effects.

“Dosing was pretty vigorous,” Rush said, “and might be a bit more vigorous than you would find in routine practice.”

The bottom line of the acute-outcomes data, Rush said, is that over the four acute treatment steps, 67 percent of the patients achieved remission.“ That's a pretty good overall outcome, but it assumes that everyone stays in treatment as long as it takes to reach remission—it assumes no dropouts.”

Long-Term Outlook: Remission Elusive

In the follow-up phase, the STAR*D protocol recommended that patients continue their previously effective acute treatment medication(s) at the doses used during acute treatment.

The most important finding from the follow-up phase of the study, Rush said, is “that the more steps a patient has to take to be well enough to go into follow-up, the worse the longer-term prognosis is.”

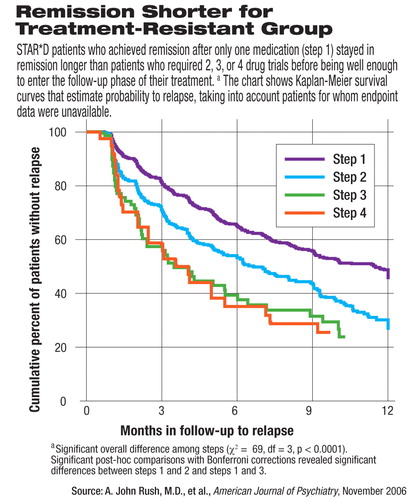

For example, he said, after six months of follow-up, about 65 percent of patients who entered follow-up from step 1 remained well (while about 35 percent had relapsed). In contrast, at the six-month follow-up, only about 53 percent of patients from step 2 remained well, compared with less than 40 percent of those from either step 3 or step 4 (see chart).

“This is very discouraging,” Rush continued. “After working hard through multiple steps, the patient is finally well enough to enter follow-up, then the medication that got them well enough to begin with doesn't keep them well over the longer-term.”

Usually, he continued, “when people talk about treatment resistance, they are referring to not being able to get the patient well enough to begin with. But now we need to expand our thinking on what constitutes treatment resistance. Now we've got a second issue—of not being able to keep the patient well.”

There is also something else implicit in the survival curves, Rush said. In step 1, two-thirds of patients entering follow-up were in remission, whereas only one-third of patients entering follow-up from steps 3 or 4 were in remission.

“We now see some evidence,” Rush theorized, “that the more steps [needed] to get to follow-up, the more likely it may be that the doctor and the patient are accepting something short of remission, a sort of `this is as good as it gets.'”

The patient, he continued, may be thinking, `Well, I've tried really hard over a long period of time, and yes, I am a whole lot better. But, even if I'm not completely in remission, let's not risk changing anything.'”

However, settling for less than remission may not be a good decision over the longer-term.

“[P]eople who entered [follow-up] in remission had a significantly better long-term result—that is, in avoiding relapse—compared with those who went into follow-up not in remission,” Rush explained.

So, the take-home message, Rush emphasized, is that a positive longer-term prognosis for patients with depression is dependent on achieving and sustaining full remission, regardless of how many treatment steps it takes to get there.

“It also tells us,” Rush added, “we must be more vigilant with patients who are in follow-up, especially [with] those who have required several steps to get there.”

Nonetheless, over the longer term, the STAR*D results confirm that major depression is a chronic, remitting-relapsing disorder. They also“ highlight the need for more effective short- and longer-term treatments, to both achieve and sustain remission in more patients earlier in their treatment sequence.”

“Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report” is posted at<www.ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/163/11/1905>.▪