Twins Find Common Cause After Illness Divides Them

Psychiatrist Carolyn Spiro, M.D., was sleeping in the on-call room at Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Boston one night in 1981 when an urgent call came from a nurse working at the state psychiatric hospital in Connecticut.

It wasn't one of Spiro's patients who'd been admitted, but her twin sister, Pamela Wagner.

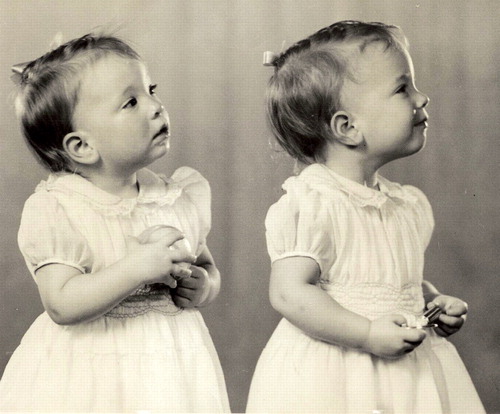

Like many twins, the two shared many of the same attributes and life experiences: dark eyes and slight builds, quick intellects, undergraduate years at Brown University, and even admission into medical school.

But after Spiro made her way to the hospital, where her sister was frozen in a catatonic stance with one arm extended into the air, the similarities between them seemed to fall away. “This can't be my twin,” Spiro remembered thinking at the time.

In a recent interview with Psychiatric News, Spiro said that although she knew her sister had emotional problems and engaged in self-injurious behavior, she had denied any possibility that Wagner had serious mental illness. “Psychiatrists use the same defense mechanisms that others do,” she noted. “I defended against the realization that a family member was actually suffering from the same illness I treated on the very wards where I learned how to be a psychiatrist,” said Spiro.

The truth could no longer be avoided when hospital staff told Spiro that her sister had schizophrenia.

Was She Psychiatrist or Sister?

Spiro said it was difficult to know how to behave during the trip to the state hospital.

“I knew I was there to support Pammy as my sister, but I didn't know what to do with the part of myself that had been on call in a very similar hospital the night before and taking care of patients just like her,” she said.

As it turned out, Wagner ended up hospitalized because she had stopped taking her antipsychotic medications; she required multiple hospitalizations over the next two decades.

“All those drugs made me feel horrible—dull and dead—everything I didn't want to be if I was going to write poetry,” Wagner told Psychiatric News. When she went off her medications, she'd be in “seventh heaven,” she recalled,“ until the paranoia and obsessions hit.”

Over the years, Wagner wrote poetry and award-winning articles pertaining to mental health. In addition, she wrote a memoir about her experiences with mental illness and treatment, which would later be integrated into Divided Minds, a book the sisters wrote together between 2000 and 2003.

St. Martin's Press published the book last year.

Twins' Lives Diverge

The book tells the story from the alternating perspectives of Wagner and Spiro as they recount their lives and sometimes profoundly different experiences of certain events.

For instance, when the twins were in the sixth grade and President Kennedy was assassinated, Spiro felt shocked, as did many of her peers. Wagner, however, became crippled by terror and felt that she was to blame for the tragedy. “I believed that I killed Kennedy,” she said.

As the twins matured, their relationship became characterized in part by rivalry as they struggled to distinguish themselves from one another.

“If Pammy did something first, I always felt like she owned it,” Spiro said. “I was doomed to be in the position of imitator.” Spiro never blamed her sister for being in front, she explained. “It was my fault that wherever I looked, I saw her back.”

Though Wagner was plagued by increasingly threatening auditory hallucinations throughout high school, she excelled academically and managed to keep the psychosis a secret, even from her sister.

When the twins began attending Brown University, Wagner became increasingly isolated and spent a great deal of energy trying to seek refuge from the voices and nonsensical thoughts that flooded her mind. She swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills in her freshman year and was hospitalized.

Though both Wagner and Spiro attended medical school, Wagner dropped out in her second year.

Spiro explained that when her sister became ill, “she left the door open for me, and when I walked through, the horizon was clear.” By this she meant that when Wagner became incapacitated by mental illness, Spiro was free of the rivalry that existed between them. “I began to try new things because I no longer assumed that I would fail,” she said.

Spreading Message of Hope

Spiro embarked upon a career in psychiatry, which she believes is the“ most fascinating area of medicine,” but also admitted that her sister's illness gave her “an excuse to be a psychiatrist.” She is now in private practice in Wilton, Conn.

Over the past several years, Wagner has found a successful combination of medications and has been “coping and doing well,” she said.

Wagner remarked that writing the book has brought them closer together, and though they were “perfectly attuned to one another” toward the end of the writing process, the going was sometimes rough.

“Pam was in and out of the hospital more times than I can count,” Spiro said. “I was carting notes and manuscripts back and forth to a number of different hospitals around the state.”

During this time, Spiro was having her own difficulties. “I was going through a divorce, but Pam was still able to be emotionally supportive,” she noted.

Since the book's release, Spiro and Wagner have been traveling around the country to share their experiences at book signings and meetings of the National Alliance on Mental Illness. “Our main message is that mental illness should not be pushed into the closet,” said Spiro. “We encourage people to seek treatment and know that there is hope for recovery.”

Spiro noted that their speaking engagements have opened up new worlds for Wagner.

Before the book tour, Wagner had never spent a night in a hotel and had seldom dined in restaurants. “Here is this incredibly bright woman who reads everything and knows a lot from books, but hasn't experienced a lot of things,” remarked Spiro.

Though public speaking can be a daunting task for anyone, Wagner said that it is “absolutely worth it to stand in front of crowds and speak if I can help people like me hang onto hope for a better tomorrow—to put one foot ahead of the other and keep walking.” ▪