'Give an Hour' Program Gets APA Support

Retired psychiatrist Daniel Benor, M.D., stands ready to donate an hour a week to American troops and their families who need help with the psychological reverberations of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Benor is just one of a thousand mental health professionals who have signed up with Give an Hour, an organization founded to fill the gaps in mental health care for military personnel and their loved ones.

Clinical psychologist Barbara Romberg, Ph.D., is the founder of Give an Hour.

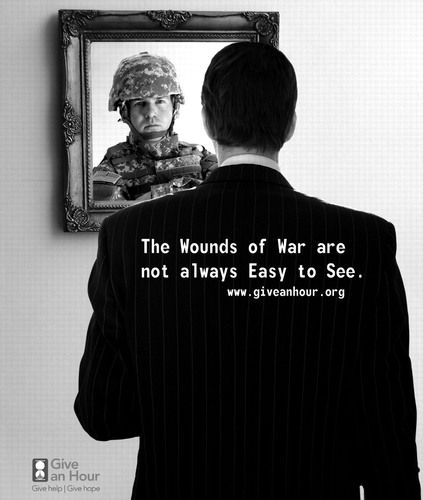

Photo courtesy of Give an Hour

Although the U.S. armed services offer a variety of mental health services, some troops have difficulty accessing them, especially those in the National Guard or Reserve who live far from military bases, founder Barbara Romberg, Ph.D., a psychologist in private practice in Washington, D.C., told Psychiatric News. Others may prefer discussing their concerns with someone outside the military system, fearing adverse effects on their careers. Still others may not live near providers authorized by TRICARE, the Pentagon's contract health system; may not be covered for some services; or can't get care when they need it.

For instance, TRICARE does not cover marital counseling even if the primary patient receives individual therapy under its plan, said Romberg.

She also cited the case of a young man distraught over the death of his uncle in Iraq. Officially, the nephew was not closely related enough to receive care in the military system, but Give an Hour's definition of“ family” is more flexible, and the organization connected him with an appropriate provider.

The program also helped a wife worried about her husband and arranged for them to get counseling through their church. One provider even received an e-mail from a captain serving in Iraq asking for help.

“Our goal is not to replace the existing systems available to our troops, but to be an additional resource when those are insufficient or unavailable,” she said.

Benor offers some directly applicable experience beyond his training. He served as a psychiatrist in the Air Force during the Vietnam War era and expects that his knowledge of military culture will help him now.

“Since uniformed therapists' records are open to unit commanders, many military people prefer to seek care from outside the system than inside,” he said.

Counselor David Beigel, M.S., of Falls Church, Va., has met for over three months with the wife and two children of a soldier serving in Iraq, helping them cope with the father's absence, their worries about his safety, and tensions between the siblings.

“I was horrified by how Vietnam veterans were vilified by both opponents and supporters of that war, so I am ready to do anything I can so that this generation will not have to face the same experiences,” Beigel told Psychiatric News.

Give an Hour is now working with the Department of Defense, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the National Guard Family Program, and others to publicize the program. An article in the April issue of Ladies' Home Journal details Give an Hour's approach.

APA has agreed to support the organization, the first major medical association to do so. APA's Healthy Minds, Healthy Lives Web site will soon contain pages informing viewers about Give an Hour.

“Regardless of their views on the war, the great majority of Americans support the troops who have served and their families, but the system isn't set up to handle the need,” said APA President Carolyn Robinowitz, M.D., in an interview. “All of us are looking for ways to be helpful. One answer is to volunteer for an hour a week, and I would encourage psychiatrists to consider Give an Hour as one way to provide needed support.”

Besides asking members to volunteer, APA is also assisting Give an Hour by helping it raise funds to produce public service announcements to increase awareness of the program, said Paul Burke, executive director of the American Psychiatric Foundation. Burke, who will guide APA's part of the fundraising effort, plans to seek corporate and foundation support for the partnership.

APA will also emphasize military mental health during Mental Health Month in May.

So far, roughly equal numbers of psychologists and social workers, and somewhat fewer psychiatrists, marital therapists, and pastoral counselors, have signed up. Romberg said that the current total recently topped 1,000 volunteers and hopes that number will eventually swell to 40,000, or about 10 percent of all mental health providers in the United States.

Give an Hour verifies that volunteer providers are in good standing and licensed by appropriate state regulatory bodies, but other than that, it does not prescreen providers or potential clients (who Romberg calls“ visitors”). Providers must carry their own malpractice insurance. However, the program is in the process of applying for status as a free clinic, which Romberg hopes will permit another layer of coverage for providers who contribute their services without charge. At present, providers still have to work within the states in which they are licensed, she said.

She is also working to develop a way for psychiatry residents and other professionals in training to volunteer under appropriate supervision.

Volunteers must commit to giving their services for an hour a week for a minimum of one year. They may provide services in face-to-face office visits, over the phone, or through other institutions like schools. Benor is prepared for long-distance consultations, having taught de-stressing techniques to his patients over the phone for several years.

No money changes hands between providers and visitors, said Romberg. Insurance companies aren't involved, saving time and paperwork. Although the patients don't pay for the services they receive, they are encouraged to perform some volunteer service in their own communities as a form of societal recompense.

“It's not required, but most are willing, and it also gives people who have gone through a rough time a sense of competence and mastery,” she said.

Give an Hour has an ongoing relationship with TRICARE, which has offered to get the word out to its members, said Romberg. Perhaps more mental health providers in the armed services or affiliated with contractors might be a preferable solution to the current shortage, said Romberg.

“But that's for someone else to work out,” she said. “I'm coming at this from humanitarian grounds. This is a way that we as citizens can help soldiers and their families.”

The Give an Hour Web site can be accessed at<www.giveanhour.org/cms/index.php>.▪