Depression in Some Teenagers May Be Preventable

The search for ways to prevent mental illness is gaining considerable ground as a field of scientific inquiry—and with some very encouraging results (Psychiatric News, April 3).

Two new studies underscore this point, finding that depression can be prevented in teenagers who have risk factors for developing the disorder.

One study was published by Judy Garber, Ph.D., of Vanderbilt University and colleagues in the June 3 Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA). The other, conducted by Edward Craighead, Ph.D., director of the Child and Adolescent Mood Disorder Program at Emory University, and Eirikur Orn Arnarson, Ph.D., an associate professor at the University of Iceland Faculty of Medicine, was published in the July Behavior Research and Therapy.

The foundation for the study by Garber and colleagues was laid eight years ago when Gregory Clarke, Ph.D., of the Kaiser Permanente Center for Health Research in Portland, Ore., and colleagues reported that a brief, group cognitive restructuring program could reduce the incidence of depression in teens with subdiagnostic depressive symptoms whose parents had a history of depression.

In this program, teens were taught how to identify and challenge irrational, unrealistic, or overly negative thoughts, with a special focus on beliefs related to having a depressed parent—for instance, “I'm doomed to become depressed because my father is depressed, and there's nothing I can do about it.”

Garber and her group decided that they would try to replicate and extend the findings by Clarke and colleagues.

Theirs was a randomized, controlled trial conducted in four cities. Subjects were 316 teenagers who had parents with a history of depression and who themselves had a history of depression or subdiagnostic depressive symptoms.

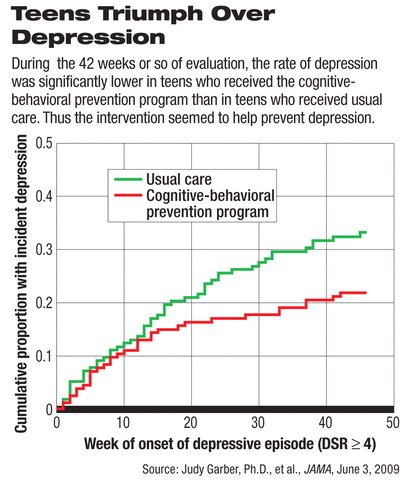

Half of the subjects were randomly assigned to usual care, which meant that they could access mental health services as they felt they needed them. The others were randomly assigned to a cognitive restructuring program. The program consisted of eight weekly group sessions followed by six months of“ booster” sessions. Subjects in both groups were evaluated for depression at the start of the study, at about 14 weeks into the study, and finally at approximately 42 weeks after the study had begun. The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children, Epidemiological Version, was used to assess depression.

The rate of depression after 42 weeks was significantly lower in the cognitive restructuring group than in the usual-care one—21 percent versus 33 percent. So the program “had a significant prevention effect,” Garber and her team concluded. Moreover, their findings showed that the program can be “reliably and effectively delivered in different settings by clinicians outside of the group who originally developed the intervention.”

As for the study conducted by Craighead and Arnarson, the sample included 171 14-year-olds at risk of depression either because of depressive symptoms or because of having indicated a negative outlook on life. Half served as controls and half received an experimental program. The program consisted of 14 group sessions conducted in school, but outside regular classroom time. Subjects learned strategies for coping with adversity—strategies that the researchers hypothesized would make the subjects resilient to depression.

After the sessions were over, subjects in both groups were followed for six months to determine whether any developed depression. They were evaluated by psychologists in structured clinical interviews using the Child Assessment Scale.

By the end of the follow-up period, 13 percent of the controls had been diagnosed with a full-blown depression or with dysthymia, while only 2 percent of the prevention program group received such a diagnosis—a significant difference. “Although I cannot [yet] disclose the exact one-year follow-up results, I can assure you that they are consistent with current data,” Craighead told Psychiatric News.

“The outcomes of this project seem to indicate that age 14 is a good age to offer a [depression] prevention program,” Craighead and Arnarson concluded in their paper. “It could become a part of a health-class sequence, or it could be implemented, as we did, in a special class setting.”

The study by Garber and her group was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The study by Craighead and Arnarson was funded by NIMH and by several Icelandic grantors.

An abstract of “Prevention of Depression in At-Risk Adolescents” is posted at<http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/301/21/2215>. An abstract of “Prevention of Depression Among Icelandic Adolescents” can be accessed at<www.sciencedirect.com> by clicking on “B,” then “Behavior and Therapy,” then the July issue. ▪