More People Seeking MH Care Than Ever Before

The number of people treated and the total cost of their care increased more for mental illness than for any other chronic health condition in a recent 10-year span, according to government figures.

The 87 percent surge in the number of people seeking noninstitutional care for psychiatric illness from 1996 to 2006 paralleled the 63 percent increase in spending on such disorders within the same period, according to data released in July by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

The findings were based on an analysis of the Household Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, which identified the five most costly conditions in 1996 and 2006. Those conditions—heart conditions, cancer, trauma-related disorders, mental disorders, and asthma—were determined by totaling and ranking the expenses for the medical care delivered for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic conditions.

The survey found that the number of people who sought care for psychiatric disorders nearly doubled in the 10-year period. In 1996, 19.3 million people incurred expenses for mental health care, while 36.2 million sought such care in 2006. The number seeking care for mental disorders was second only to the 48.5 million who sought asthma care in 2006.

The growth in the number of people receiving care for psychiatric conditions is not due to an increase in the prevalence of mental illness but rather reflects people's willingness to seek care instead of going untreated as they did in the past, said Selby Jacobs, M.D., a member of the APA Council on Healthcare Systems and Financing.

The recent AHRQ findings are “testimony to some extent on the [effectiveness of the] strategy of mainstreaming mental health benefits,” Jacobs told Psychiatric News.

The survey found that the largest increase in spending for chronic and acute health care conditions was for the category of mental disorders. Spending related to psychiatric diagnosis and treatment rose 63 percent, while the second-largest increase in spending—47 percent—occurred for trauma-related disorders.

Jacobs credited the large jump in mental health spending to the combination of a demand for care by more people with psychiatric disorders and to the“ soaring costs” of psychotropic drugs in recent years.

Other recent data also support the finding that treatment of mental illness has increased. A study in the August Archives of General Psychiatry, for example, concluded that antidepressant use among U.S. residents nearly doubled in a similar period, 1996 to 2005 (see Original article: Antidepressant Use Rises in 10-Year Period). The researchers, who included Eric Caine, M.D., chair of the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Rochester Medical Center, reported that the number of U.S. residents prescribed antidepressants rose from 5.84 percent, or 13.3 million people, in 1996 to 10.12 percent, or 27 million people, in 2005.

Spending on mental health care may further increase after implementation of the 2008 law that mandates parity in mental health coverage in most private insurance plans and another 2008 law that will make Medicare outpatient mental health services more affordable by phasing out the discriminatory copay.

The AHRQ data, however, indicated that the jump in mental health spending was not driven by the rising cost of an individual's treatment. In fact, the average annual per-person spending by patients, government programs, and private insurers fell in the 10-year span, from $1,825 in 1996 to $1,591 in 2006.

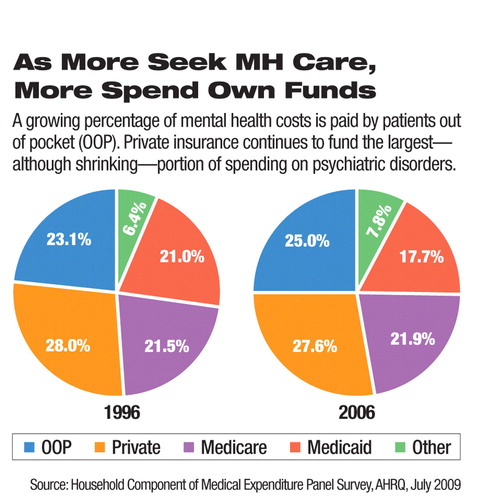

Despite the drop in the overall cost of mental health care, out-of-pocket costs have risen for patients. Out-of-pocket payments for the treatment of psychiatric disorders were among the highest for all disorders in both 1996 and 2006 (see chart). These payments rose from 23.1 percent of the average amount individuals spent on mental health care in 1996 to 25 percent in 2006.

That patient spending increase is consistent with the fact that many solo mental health clinicians, including psychiatrists, practice outside of managed care systems and are thus less likely to accept a managed care benefit, Jacobs said.

A summary of the “Five Most Costly Conditions, 1996 and 2006: Estimates for the U.S. Civilian Noninstitutionalized Population” is posted at<www.meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/data_files/publications/st248/stat248.pdf>.▪