Road Map Shows Route From Punishment to Treatment

Abstract

A 62-year-old woman making a call from a Washington, D.C., subway pay phone refuses to relinquish the phone to another commuter impatient to use it.

A fight ensues, and the police are called. When approached by the police, the caller begins to yell at them, refusing to leave the premises. She is arrested for disorderly conduct, trespassing, and resisting arrest.

Taken to a hospital, she appears to be hearing voices and expresses the belief that she is “the president.” She initially refuses medication, but after a few days she develops a relationship with one of the nurses who is able to persuade her to begin taking medication.

The incident was recounted in a June 21, 2010, Weblog by forensic psychiatrist Erik Roskes, M.D., on “The Crime Report” at <www.thecrimereport.org> under the title “The Charge: Being Mentally Ill in Public.”

In the report, Roskes—who was the forensic psychiatrist assigned to evaluate the woman's fitness to stand trial—recounts calling the arresting officer and inquiring why the woman wasn't taken immediately to the emergency room. The officer replied, “She wasn't doing anything dangerous. They wouldn't have taken her.”

In his blog, Roskes asked, “What is wrong with our system that a person can be perceived by a police officer as being dangerous enough to require arrest and detention in jail, but not dangerous enough to be admitted to a hospital for treatment?”

It's a question that has long gone unanswered, even as the criminalization and incarceration of people with mental illness has skyrocketed from year to year. A report in May by the Treatment Advocacy Center found that Americans with severe mental illness are now three times as likely to be in jail as they are to be in a hospital (Psychiatric News, June 4).

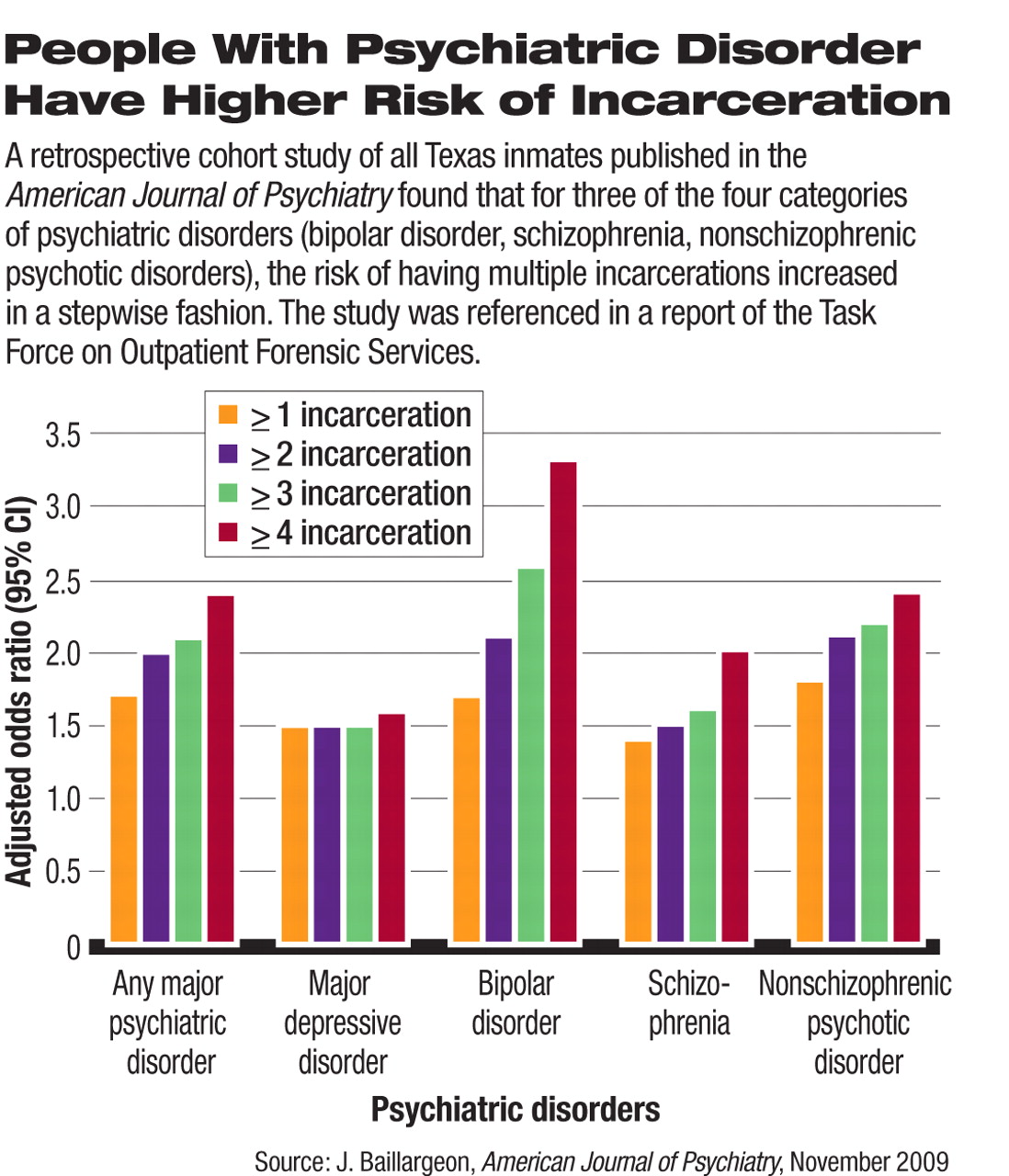

Roskes is a member of APA's Task Force on Outpatient Forensic Services, whose report “Outpatient Services for the Mentally Ill Involved in the Criminal Justice System”—approved by the APA Board of Trustees in December 2009—outlines historical reasons for criminalizing this population in the last 30 years, reviews evidence regarding the impact of ordinary outpatient services on rates of incarceration of mentally ill individuals, provides an overview of the characteristics of mentally ill individuals in the justice system and the risk for violence, and describes model treatment approaches to those with mental illness involved in the justice system.

And it issues a strident wake-up call to psychiatrists who remain—in the view of the task force—underinformed about this alarming civic trend toward criminalization and underinvolved in responding to it.

Few Know Extent of Problem

“The psychiatric community is becoming increasingly aware of the problems of correctional mental health care,” the report stated. “Few, however, are aware of the magnitude of how many public-sector patients now fall within the domain of the criminal justice system and are destined to receive poor care and follow-up. Nor are most psychiatrists aware that the prison environment is antitherapeutic, engendering maladaptive behavioral patterns that render future care more difficult.... [I]t is no longer possible to believe that problematic patients not served by public-sector psychiatrists are receiving good care in the criminal justice system.”

Past APA President and forensic psychiatrist Paul Appelbaum, M.D., was chair of the Council on Psychiatry and Law when the task force was formed. “Other countries, including Canada and England, are far ahead of the U.S. in recognizing that patients coming out of correctional facilities have particular characteristics and special needs,” Appelbaum told Psychiatric News. “The council requested this report because we believed that it was time for American psychiatrists to think seriously about how best to meet the treatment needs of this growing and often neglected population.”

‘A Perfect Storm of Criminalization’

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Task Force Chair Steven Hoge, M.D., said bluntly, “Correctional psychiatry is the new public psychiatry.”

Hoge, who is director of the Columbia-Cornell Forensic Psychiatry Fellowship Program, said the turn toward criminalization of individuals with mental illness has historic roots involving multiple factors—diminishing availability of public psychiatry beds, an increasingly punitive approach in the “war on drugs,” increasing hostility on the part of a public fearful of mentally ill people and the perceived risk of violence, and greater involvement of legislatures, as opposed to courts and judges, in mandating sentencing.

The result, he said, “has been a perfect storm of criminalization.”

This has happened in the context of a sharp rise in incarceration generally. “If you look at the incarceration curve for the general population, it has gone up from 100 per 100,000 to 900 per 100,000,” Hoge said. “It's extraordinary. The United States has the highest rates of incarceration of any country in the world, including some of the most repressive regimes.

“It's ironic that just as we have been deinstitutionalizing people with mental illness, the society has taken a wholesale turn toward a punitive approach to deviant behavior,” he told Psychiatric News. “We are more likely to charge someone with possession [of drugs] than to try to find a treatment program for someone who is an addict.”

Among the summary conclusions outlined by the task force are the following:

| •. | The quality of care in correctional settings varies from nonexistent to adequate. In general, psychiatric care in jails and prisons is fragmented and inconsistent. | ||||

| •. | For an outpatient-based system to function in providing better care for mentally ill offenders, better access to inpatient beds is necessary. | ||||

| •. | There is evidence that mandated outpatient treatment may be useful in reducing rates of arrest and incarceration when properly funded and monitored. | ||||

| •. | Programs must be designed to treat and manage patients with comorbid substance abuse problems and antisocial personality disorder, and outpatient programs must be prepared to address the problems related to chronic disability, unemployment, and homelessness. | ||||

| •. | Mentally ill women in the criminal justice system have special needs due to high rates of trauma history and PTSD. In addition, many will need assistance in parenting, supporting, and providing care for children. | ||||

| •. | Models for caring for mentally ill offenders exist in other countries. They may be useful as starting points in designing a system for the United States. | ||||

The task force offers four recommendations for the field of psychiatry (see See also: What Psychiatrists Can Do).

“The overall message is that these are our patients,” Roskes told Psychiatric News. “People with mental illness who are involved in the criminal justice system are and should be of interest to every psychiatrist.”

Roskes, who does not stint on criticism of organized psychiatry for failing to be more involved in the issue, said other groups—the National Alliance on Mental Illness, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, the Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, and the Council of State Governments—have taken the lead in working on alternative treatment approaches to criminally mentally ill people.

He added, “A history of arrest is not the same as a history of violence. I work in a state hospital where two-thirds of our patients are forensic. Clinically they are no different from the nonforensic population except that they have gotten caught. But people are afraid of this population, and that is to our discredit as a field.”

“Outpatient Services for the Mentally Ill Involved in the Criminal Justice System: A Report of the Task Force on Outpatient Forensic Services” is posted at <www.psych.org/TFR200921>.