Timing of Certain PTSD Treatments Doesn't Appear to Be Crucial

Abstract

Cognitive or exposure therapies, whether begun immediately or after some delay, are effective in preventing chronic posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in symptomatic survivors of traumatic events, according to a major study by Israeli researchers.

However, the use of an SSRI antidepressant appeared to have no effect compared with placebo, and patients on the medication did worse than all other cohorts at the end of nine months, reported Arieh Shalev, M.D., and colleagues in an October 3 online report in Archives of General Psychiatry

Related results from the same study were also reported in the July Psychiatric Services.

Trauma survivors reporting distress should be diagnosed carefully, and those with PTSD symptoms should be offered early cognitive-behavioral or exposure-based therapies, wrote Shalev, a professor of psychiatry at the Hebrew University and the Hadassah School of Medicine in Jerusalem. "Future studies should further evaluate the timing and efficacy of the early use of pharmacotherapy for the prevention of PTSD."

"The finding that an SSRI was not effective is surprising," said Douglas Zatzick, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral science at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

SSRIs are recommended in most treatment guidelines for PTSD, but along with other pharmacotherapies were judged by an Institute of Medicine committee in 2007 as having only modest levels of evidence to support their use.

In the Israeli study, conducted from 2003 to 2007,the researchers reviewed within 24 hours of admission records of all trauma cases at the emergency department at Hadassah University Hospital in Jerusalem. Most had experienced trauma in motor vehicle accidents, the others in terrorism incidents or work accidents.

A total of 5,286 eligible survivors were called by telephone and 4,753 agreed to be interviewed. They were then screened using DSM-IV criteria A1 and A2. Survivors with a confirmed traumatic event (n=1,998) received a full structured interview. Of those, 1,502 were offered a full clinical assessment and 756 accepted.

Eventually, 242 participants with full PTSD symptoms were randomized to four treatment options: prolonged exposure, cognitive therapy, escitalopram/placebo, and a waiting list.

The decreasing numbers of patients agreeing to participate in the evaluation indicated that even among symptomatic persons contacted systematically, there was limited willingness to accept evaluation or treatment.

The research staff spent nearly seven hours on the telephone and five hours of clinical assessment time to bring one patient into treatment.

"The study shows how hard it is to get people into therapy, even after making phone calls to 5,000 individuals," said Zatzick.

"[T]he main source of this burden is the unavoidable inclusion in early assessments of persons who experience early symptoms and spontaneously recover," wrote Shalev and colleagues.

Nevertheless, an advantage of the study is that in Israel, a small country, it is relatively easy to follow up with people, said Zatzick, who is a member of an Institute of Medicine panel examining diagnosis and treatment of PTSD (Psychiatric News, June 3).

Participants were reassessed at five months and nine months.

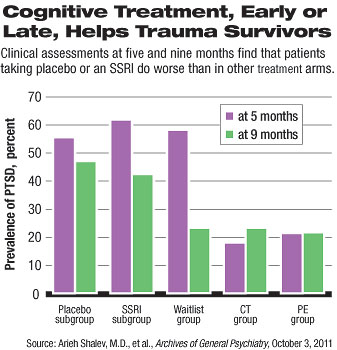

At five months, prevalence of PTSD in the prolonged exposure and cognitive therapy groups was significantly lower than in the SSRI, placebo, and waitlist groups (see chart).

At the nine-month assessment, prevalences of PTSD in the prolonged exposure, cognitive therapy, and waitlist groups were all about 22 percent.

"Our finding suggests that delaying the intervention does not increase the risk of chronic PTSD," said the authors. "[A] delayed intervention is an acceptable option when early clinical interventions cannot be provided (e.g., during wars, disasters, or continuous hostilities)."

Furthermore, at the nine-month follow-up, participants in the SSRI (42 percent) and placebo (47 percent) groups had much higher rates of PTSD.

However, because the trial's design permitted participants to refuse drug treatment, a relatively smaller sample size in the SSRI/placebo arm "does not yield enough statistical power to refute a potential preventive effect."

The study did not include an arm using both pharmacotherapy and cognitive/exposure therapy.

More extensive trials of pharmacotherapy should be a topic for future research, said Shalev.

Finally, the researchers looked at information they gathered at five months from survivors who declined either assessment or treatment and noted that they improved less than those who accepted either.

"[T]his finding suggests that declining care does not reflect inner strength or resilience," they concluded.

An abstract of "Prevention of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder by Early Treatment: Results From the Jerusalem Trauma Outreach and Prevention Study" is posted at < http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/short/archgenpsychiatry.2011.127 >.