Depression-Cardiovascular Link Found in Young Adults

Abstract

During the past few years, scientists have found troubling associations, in middle-aged and older adults, between depression and death from cardiovascular disease.

For example, there is now a well-documented, positive correlation between depression-symptom severity and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. The more severe the depression, the higher the likelihood of developing cardiovascular disease and dying from a heart attack (Psychiatric News, April 4, 2008).

And now it appears that depression can contribute to fatal cardiovascular disease not just in older individuals, but in younger ones as well, scientists reported in the November 2011 Archives of General Psychiatry.

The study’s senior investigator was Viola Vaccarino, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of medicine at Emory University.

The study that Vaccarino and her colleagues conducted was based on a large nationally representative sample of young American adults (7,641 individuals). The subjects, who were aged 17 to 39 at the start of the study, were evaluated not just for conventional cardiovascular risk factors, but also for current or past unipolar or bipolar depression and whether they had ever attempted suicide.

Depression was assessed with the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, a standardized clinical instrument based on DSM-III criteria. A history of attempted suicide was also obtained during administration of the Diagnostic Interview Schedule with the question: “Have you ever attempted suicide?”

A total of 538 subjects out of the 7,641 who were assessed were identified with current or prior depression (416 with unipolar depression and 122 with bipolar depression), and 419 had attempted suicide. Considerable overlap existed between depression and attempted suicide, with 136 of the subjects having made a suicide attempt as well as having current or past depression.

The subjects were then followed for an average of 15 years to determine whether any had died from cardiovascular disease. The deaths of 51 subjects were attributed to cardiovascular disease—28 from ischemic heart disease, eight from cerebrovascular causes, and the remaining 15 from other cardiovascular disease causes.

The researchers then assessed whether a diagnosis of unipolar or bipolar depression was significantly linked with a later death from cardiovascular disease, while taking potential confounders such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, cardiovascular risk factors, and lifestyle factors into consideration.

Subjects who had been depressed were twice as likely to experience a fatal cardiovascular event as those who had not been depressed. And when the analysis was limited to women, those with depression were three times more likely to experience a fatal cardiovascular event than those who had never had a depression diagnosis.

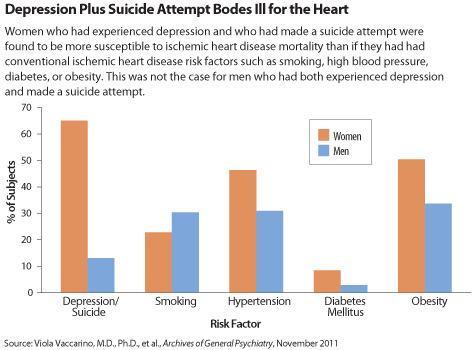

In addition, a history of attempted suicide was also a significant independent predictor of cardiovascular disease mortality in both genders. But this was especially so in women. Women who had experienced depression and made a suicide attempt were found to be more susceptible to ischemic heart disease mortality than if they had had conventional ischemic heart disease risk factors such as high blood pressure, smoking, diabetes, or obesity.

So how might depression lead to cardiovascular mortality in young adults? Psychosocial stress is probably responsible for both the depression and the mortality, Vaccarino and her team believe. For instance, stress is known to be a risk factor for depression, depression is known to be a risk factor for increased cortisol secretion, and increased cortisol secretion is known to have potentially adverse cardiovascular effects.

And if this is the case, then stress reduction in young adults—especially in young women—is imperative if depression and depression-provoked fatal cardiovascular disease are to be avoided, the researchers suggested.

As to how young adults can reduce their stress, “I believe that the number-one strategy is to promote a healthy family and social environment to minimize psychological trauma in childhood and early adulthood, which is a potent risk factor for depression, particularly among women,” Vaccarino told Psychiatric News. “[Also] young people can reduce stress through exercise, which is also beneficial for heart-disease prevention, or through stress-reduction programs such as various forms of meditation. [And] in some cases, psychotherapy may be recommended.”

Although Vaccarino and colleagues suspect that in young adults psychosocial stress is the major reason why depression leads to cardiovascular disease, other factors probably play mediating roles as well, studies have suggested. These include alterations in the immune system, notably in inflammatory cytokines, defects in platelet clotting, and decreased heart-rate variability, a well-documented risk for a heart attack.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Emory University General Clinical Research Center.

An abstract of “Depression and History of Attempted Suicide as Risk Factors for Heart Disease Mortality in Young Individuals” is posted at http://archpsyc.ama-assn.org/cgi/content/abstract/68/11/1135.