New Uses of Brain Imaging Get Closer to Clinic

Abstract

PET scan findings suggesting that the insula could be a useful biomarker for selecting depression treatment might be the next brain imaging findings to be developed into a clinical tool.

During the past decade or so, psychiatric brain imaging has led to a raft of provocative discoveries.

For example, men with schizotypal personality disorder have reduced matter in a number of brain areas, Robert McCarley, M.D., chair of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, and his colleagues have found.

Brain structure abnormalities in girls with conduct disorder may help explain their lack of empathy, Graeme Fairchild, Ph.D., of the University of Southampton in England, and colleagues believe.

In addition, neuroimaging may prove useful for predicting which patients with social anxiety disorder may profit the most from cognitive-behavioral therapy, according to a study headed by Oliver Doehrmann, Ph.D., of Massachusetts Institute of Technology and published in the January 2013 JAMA Psychiatry.

In addition to providing insights into the biological underpinnings of psychiatric illnesses, these discoveries have a broader implication for the field of psychiatry, Caleb Adler, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and director of the Center for Neuroimaging Research at the University of Cincinnati, said during a recent interview with Psychiatric News.

“A lot of the neuroimaging studies over the last five years have confirmed the biological nature of much of psychiatric illness. For example, as new studies come in, it is becoming clearer and clearer that schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder are organic illnesses that need to be treated like other medical illnesses. That has helped change the direction of psychiatry, I think.”

Moreover, brain imaging is starting to deliver on the promise of clinical utility.

“We are seeing a growing introduction of both structural and functional neuroimages . . . in court in connection with a variety of claims, ranging from the use of such information to support diagnostic claims to [establishing] impairment of function or the presence of injuries,” Paul Appelbaum, M.D., said. Appelbaum, a former APA president, is the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University and chair of the APA Committee on Judicial Action.

Two brain imaging tests—a PET imaging technique using the radioactive tracer FDG and one using the radioactive tracer florbetapir—have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for clinical use, Jorge Barrio, Ph.D., a professor of molecular and medical pharmacology at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), told Psychiatric News.

Each of these tests has its pluses and minuses, pointed out Gary Small, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at UCLA and an Alzheimer’s disease (AD) brain imaging researcher.

For example, the FDG test has both high specificity and sensitivity in detecting AD; can differentiate AD from other dementias such as frontal temporal dementia, which can be helpful since drugs that can temper AD symptoms do not help in frontal-temporal dementia; and is covered by Medicare. However, it is not useful for patients with diabetes.

The florbetapir test shows a strong signal that indicates a heightened likelihood that a patient has AD. But it has not been shown to be any more accurate than the FDG test in confirming the presence of AD. And Medicare does not cover it.

Shortly before this article went to press, yet a third radioactive tracer—flutemetamol—was approved by the FDA for use with PET imaging in evaluating individuals for Alzheimer’s and dementia. Currently, flutemetamol is not covered by Medicare.

In addition, brain imaging is being used by clinical psychiatrists in ways that they tend to not think about, Adler pointed out. “For instance, it is fairly routine to order an MRI scan for a patient with a first episode of psychosis to rule out a tumor or stroke as a cause.”

Best May Be Yet to Come

But the best brain imaging clinical applications are still on the horizon.

For example, PET scan study findings recently published by Helen Mayberg, M.D., a professor of psychiatry, neurology, and radiology at Emory University, and her team may be the next to be transformed into a clinical tool. This is the opinion of two Harvard Medical School brain imaging researchers—psychiatrists David Silbersweig, M.D., and Joshua Roffman, M.D.

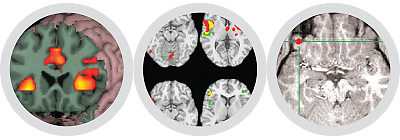

Psychiatric brain imaging is starting to deliver clinical utility—for instance, in geriatric psychiatry and forensic psychiatry. | |||||

Additional clinical uses of brain imaging for psychiatric practice are on the horizon. | |||||

Brain imaging findings by Helen Mayberg, M.D., and her team regarding treatment responses in patients with major depression may be the next to be used clinically. | |||||

Multiple hurdles still need to be overcome before brain imaging can be extended clinically—for instance, it is expensive to develop the technology, and funding is a major issue. | |||||

Mayberg and her colleagues found that metabolism speed in the insula region of the brain predicted whether individuals with major depression would respond to an SSRI antidepressant or to cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Subjects who had high metabolism in the insula did well with an SSRI and poorly with CBT, while subjects who had low metabolism in the insula did well with CBT and poorly with an SSRI.

“An obvious next step is to see whether we can improve remission rates if we assign treatment based on the brain type,” Mayberg told Psychiatric News. “The subjects with high insula activity would get the drug, and the subjects with low insula activity would get CBT. We have a competitive grant renewal application currently under review at the National Institute of Mental Health. . . . This would be a prospective testing of the utility of the insula biomarker.”

There is another issue, though, she acknowledged. PET brain imaging is expensive. So if the insula turns out to be a useful biomarker for stratifying treatment, “we can then search for a less costly nonimaging surrogate.”

Indeed, a general barrier to turning brain imaging into clinical tools, Small noted, is that “it’s expensive to develop this technology. Funding is a big issue.”

Obstacles Can Be Surmounted

Nonetheless, experts in the field are optimistic that such obstacles can be eventually overcome, ushering in new clinical possibilities for imaging.

Brain imaging researchers are also starting to use new technologies that they believe might help pave the way for clinical applications. They are likewise taking certain tacks that should spur the field in a clinical direction.

For instance, “I think there is an increasing trend toward incorporating therapeutics into longitudinal outcomes in imaging,” Silbersweig observed. “A prime example is the recent work conducted by Mayberg and her group. This trend is important in moving imaging more towards translational relevance….”

And “having the opportunity to combine individuals’ genomic data with brain imaging could eventually be a powerful clinical tool,” Roffman stated. “It seems inevitable that genetic information is going to be part of someone’s medical record. The cost of gene sequencing has come down exponentially and will continue to do so.”

“Brain imaging has provided us with a historic opportunity to understand how the brain works in healthy individuals and how its function is disrupted in individuals with psychiatric disorders,” Roffman stated. “It is a fantastic research tool. At the same time, ultimately, we’re hoping that it will be a powerful clinical tool as well.” ■