Expectations Deter Vets From Mental Health Care

Abstract

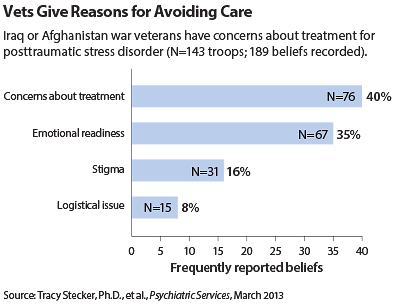

U.S. veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan wars say they worry more about psychiatric medications than stigma in avoiding treatment.

Barriers to treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among troops returning from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan remain complex, even after years of educational efforts by military and veterans health officials.

Researchers held extended (45-60 minute) phone conversations with 143 service members who had served in the war zones and who had screened positive for PTSD but were not in treatment. The goal was to learn their reasons for not entering care. Many expressed concerns about the treatment they thought they would receive.

About 40 percent of troops interviewed for a study published in the March Psychiatric Services said they did not seek treatment for mental health problems because they disliked the possible options that such care entails. They disliked group therapy, believed that they would be misunderstood by clinicians, or assumed that they would be prescribed medications but believed that medications alone would not relieve their symptoms.

“They did not understand how a medicine would help treat their trauma,” said lead researcher Tracy Stecker, Ph.D., an assistant professor of family and community medicine at Dartmouth Medical School, in an interview with Psychiatric News. They worried that a clinician would simply prescribe a drug instead of listening to the patient’s personal history of trauma.

However, the veterans mentioned stigma as a barrier only 16 percent of the time, and logistical problems (such as travel time to clinics) were cited by only 8 percent of study participants.

As part of their qualitative study, the researchers asked the troops what they thought might help them.

“If they said ‘talk,’ then we discussed with them the barriers to cognitive-behavioral therapy,” said Stecker. “Our purpose was to get them to be realistic about their expectations of available treatments.”

In addition to the 40 percent who said they avoided care because they did not like the treatment options, another 35 percent stated that they did not need treatment and were not emotionally ready to begin therapy, even though they had PTSD symptoms. In those cases, Stecker’s group suggested that perhaps taking an hour to talk about trauma might be a relief from spending 24 hours a day not talking about it.

Many troops acknowledged a need for treatment but said they would rather wait until they left military service for fear that entering care would compromise their careers or security clearances.

Stecker was surprised to learn that only 1 in 6 of the respondents said stigma was a major barrier to treatment.

“PTSD has become a kind of badge of honor,” she said. One soldier even told her that he used the diagnosis as a pickup line in bars, telling sympathetic women, “I have PTSD and I need to get help.”

Ten years ago, acknowledging that diagnosis would have been unthinkable, but not today. A decade of education and discussion in the U.S. Armed Forces about PTSD appears to be changing attitudes, she said. “People are not getting into trouble within the military for being real about having PTSD.”

However, she cautioned, such openness did not extend to other conditions, such as depression or substance abuse, which might also have their origins in combat trauma.

One thing the interviewing process revealed, Stecker said, was the importance of taking the opportunity to open a discussion about longer-term change. “You can talk to these guys on an individual basis and get them to modify their choices and get them into treatment,” she pointed out. “And we can do more to support them while they’re resisting.”

A second study in the March Psychiatric Services appears to back up some of Stecker’s conclusions.

Eunice Wong, Ph.D., of the RAND Corporation and colleagues found that in a sample of 1,659 active-duty service members, 17 percent had received mental health treatment in the prior 12 months. About 14 percent had seen a specialty mental health clinician, and 5 percent had sought help from a primary care provider. (Some may have seen both types of clinicians.)

Patients who saw the mental health specialists reported more visits (10.3 per year on average) and higher satisfaction with their care than did those only in primary care (5.3 visits per year).

“[S]ervice members may prefer the types of interventions that are more widely available from mental health providers (psychotherapy) than from primary care providers (medication),” a preference reflecting similar patterns among the U.S. population at large, Wong suggested. ■

An abstract of “Treatment-Seeking Barriers for Veterans of the Iraq and Afghanistan Conflicts Who Screen Positive for PTSD” is posted at http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=1654323. An abstract of “Mental Health Treatment Experiences of U.S. Service Members Previously Deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan” is posted at http://ps.psychiatryonline.org/article.aspx?articleid=1555238.