Rulings Guide Psychiatrists on Forced-Treatment Limits

Abstract

A conference at historic St. Elizabeths Hospital sheds light on the current status of involuntary treatment of people in the criminal justice system.

Arguments over whether individuals in the criminal justice system can be medicated against their will are unlikely to disappear soon, said two speakers at the first annual forensic psychiatry conference at St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C.

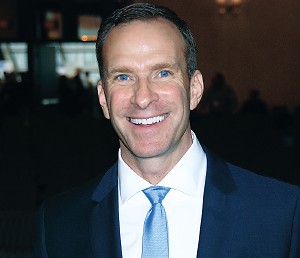

Charles Scott, M.D.: How and when defendants or prisoners can be forcibly medicated is a complex problem.

“Right-to-refuse-treatment issues are likely to increase as more people [with mental illness] are diverted into the criminal justice system,” said Charles Scott, M.D., a professor and chief of the Division of Psychiatry and the Law at the University of California, Davis. “With that, there will be more competency cases and more decisions about medication use.”

Scott appeared with Howard Zonana, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and an adjunct clinical professor of law at Yale University.

The controversy over who in the criminal justice system can and cannot be medicated is hardly new, said Scott, the immediate past president of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. The right to refuse treatment has its roots in the 19th century with cases involving standards for involuntary civil commitment.

Individuals have the right to refuse any medical treatment, but that right is not absolute, he said. The state may mandate treatment to protect others from “the dangerous mentally ill,” in the case of mentally incompetent adults, or to maintain security in a state institution such as a prison or hospital.

Several cases in recent decades have delineated when and how patients can be held or forcibly treated, said Scott.

Washington v. Harper in 1990 found that inmates with a serious mental illness who refused treatment could be medicated against their will if they were deemed dangerous to self or others, provided that the state adhered to proper procedural due process. Under Harper, that includes a hearing board that includes a psychiatrist.

Time is important, too, said Scott. In 1992’s Jackson v. Indiana, a developmentally disabled deaf-mute young man who stole $9 was committed to a state hospital until his competency to stand trial was restored. The U.S. Supreme Court found that Jackson’s competency could never be restored and that his confinement amounted to a life sentence without a conviction. A patient could be held only for a “reasonable period of time” and only as long restoration was likely, said the Court.

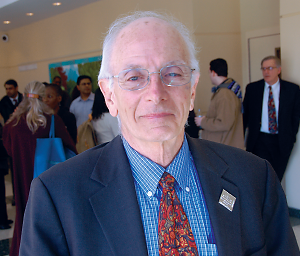

Howard Zonana, M.D.: Restoration of competency to stand trial raises numerous issues in law and medicine.

Finally, in Sell v. United States in 2003, the Court enumerated the standards for involuntary administration of medication to criminal defendants to render them competent to stand trial.

These “Sell criteria” include a serious criminal act, the likelihood that competency will be restored without serious side effects, that medication is the best way to restore competency, that it is medically appropriate, and that alternate grounds for medicating (like dangerousness) be considered first, said Zonana.

In criminal law, competency is a defendant’s ability to understand the proceedings in court and assist in his or her defense, Zonana noted. “But the need for competency goes beyond the necessity for a fair trial,” he said. “Competency is also needed for the dignity of the criminal justice process, for accuracy and reliability in adjudication, and for the autonomy of the defendant, who has a right to decide matters about his case that can’t be taken away from him.”

Competency Rulings May Not Clarify Issue

However, court rulings on competency have proven hard to interpret, he said. “Courts want to hear conclusory opinions about a defendant’s competency, not just a delineation of capacities.”

Worse yet are policies that keep people in custody for indeterminate lengths of time while awaiting competency restoration. A defendant restored to competency will be sent back to jail to await trial, but if he stops his medications and symptoms return, he will be transferred back to the hospital for restoration, and the cycle continues.

The case of Jared Loughner, the gunman in the Tucson, Ariz., shooting in which he killed six people and wounded 11 others, including then-Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, is an example of how complex such cases can be, said Zonana.

Loughner was sent to a hospital to “see if he could be restored to competency.” Because he had not yet been tried and was thus presumed innocent, he was entitled to greater constitutional protections than a convicted prisoner.

“But how is it possible to tell if someone responds to treatment if we don’t administer medications?” asked Zonana. However, since Loughner’s condition deteriorated when not taking medications, he was forcibly medicated on an emergency basis because he became violent.

Ultimately, in August 2012, Loughner was declared competent and pleaded guilty without entering an insanity plea, concluding the case, said Zonana.

Existing case law will increasingly come into play as more patients are committed involuntarily, said Scott. “You need to know your state’s law relating to medication refusal for each legal classification,” he said. “And always document dangerousness with the Harper and Sell cases in mind.”

Scott concluded by reminding his listeners about the significance of their work in forensic psychiatry.

“You are dealing with legitimate individuals struggling with mental illness that sometimes impairs their insight,” he said. “You’re trying to move forward; you know there are a lot of people who are trying to get better.” ■

Information about St. Elizabeths Hospital is posted at http://dmh.dc.gov/page/saint-elizabeths-hospital.