Could DNA Methylation Affect Suicide Risk?

Abstract

Genomewide DNA methylation changes in the hippocampus affect risk of suicide, especially in genes tied to learning, memory, and behavior.

Genomewide DNA methylation differences in gene promoter regions in the hippocampus reveal some significant associations with suicide risk, according to researchers at McGill University in Montreal.

“[O]ur findings suggest that such mechanisms may, in individuals with particular behavioral, molecular, and cellular predispositions, increase susceptibility to suicide,” said Gustavo Turecki, Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry and human genetics and director of the McGill Group for Suicide Studies, and colleagues in AJP in Advance online March 20.

“We think that epigenetic changes occurring early in life may influence how personality traits develop,” said Turecki, in an interview with Psychiatric News. “The epigenetic regulation of these processes in the brain may be altered in suicide completers, leading to the dysregulation of cognitive processes.”

The researchers studied postmortem samples provided by the Quebec Suicide Brain Bank from 46 men who died by suicide and 16 controls who died suddenly by other means and did not have a psychiatric illness.

They examined DNA methylation in promoter regions of 23,551 genes in the hippocampus. Methylation is associated with regulation of gene expression.

“We used a genomewide approach rather than a candidate-gene approach,” said Turecki. “A genomewide approach interrogates all genes in the genome rather than a single or group of genes.”

The researchers found significant differences at 366 locations between the suicide and control cohorts. Of those, 273 probes reflected hypermethylation and 93 were hypomethylated in the hippocampus.

They initially investigated the hippocampus because it is involved in stress response and is highly plastic, Turecki explained. “We are now in the process of looking at other important brain regions.”

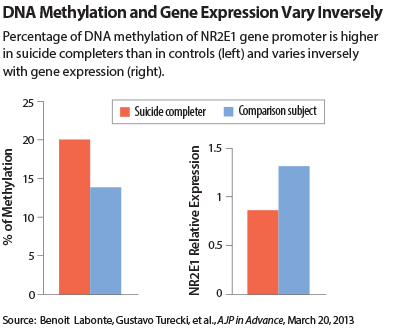

Mean gene expression and mean methylation levels were inversely correlated in the study sample.

The appearance of variable methylation across the genome suggested that “epigenetic changes in psychiatric disorders may not be limited to a short list of specific gene candidates but may affect multiple functional gene networks in multiple chromosomal regions,” the researchers concluded.

“This is an interesting study and is carefully done,” noted Lisa Monteggia, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical School in Dallas.

Methylation changes are a reliable marker because they can be detected easily in postmortem tissue due to their covalent bonds, said Monteggia, who has also studied the epigenetics of suicide and depression. However, methylation is not the only mechanism for change in DNA, she added.

Other mechanisms of epigenetic change are not so easy to track in an autopsy, she said. “Phosphorylation or acetylation are more difficult to compare because of the more transient nature of those traits.”

The McGill researchers also took a closer look at a cluster of four genes displaying particularly significant methylation differences between the two cohorts.

These were the NR2E1 orphan nuclear receptor gene; the CHRNB2 neuronal acetylcholine receptor subunit beta-2 gene; the GRM7 metabotropic glutaminergic receptor 7 gene; and the DBH dopamine beta-hydroxylase gene.

These genes are all related to cell-level processes of learning, memory, behavior, and neuronal communication, such as synaptic transmission. NR2E1 and GRM7 influence behavioral traits such as anxiety, impulsivity, and aggression, all of which are risk factors for suicide. Methylation in those genes may thus affect an individual’s ability to respond to psychosocial stress, suggested the authors.

CHRNB2 and DBH have been connected with learning and memory formation. The study observed hypermethylation without any difference in DBH gene expression between suicide completers and controls. The authors speculated that the effects of DBH on suicide risk may thus be indirect, working through its role in norepinephrine synthesis.

Nevertheless, because suicide is so complex and so much about it remains unknown, it is hard to know precisely how these processes underlie suicide risk factors, said Monteggia.

“There’s still a lot of work that needs to be done to focus into the complex of genes that actually trigger suicidal behavior,” she said. “For instance, are these genes related to the pathophysiology of suicide or to the ideation or execution of suicide?” ■

An abstract of “Genome-Wide Methylation Changes in the Brains of Suicide Completers” is posted at http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/Article.aspx?ArticleID=1669750.