DB Helps Develop Tool Kit To Help Physicians Thrive in ACOs

Abstract

As accountable care organizations become the norm in U.S. health care, malpractice carriers will need to cover liability for “curbside consultations.”

The accountable care movement and accountable care organizations (ACOs) are here to stay, and there are opportunities for professional and financial rewards for informed psychiatrists.

They have the skills and experience that position them for success in ACOs, and it is vital for psychiatrists to step up with like-minded physicians to lead in what can be a career-changing transformation.

The North Carolina tool kit on accountable care organizations (ACOs), and its section for psychiatry, provides instructions on how physicians can “get a grip” on accountable care. For instance, it notes that “at present, psychiatrists are not well-trained in some of the processes and tasks central to the ACO. Rapid change will challenge even those who are better trained in the concepts of quality assurance and other administrative and fiscal realities.”

And it suggests actions psychiatrists can take to better prepare for ACO participation, including the following:

Seek training on integrated models including the tools they use such as screening tools, communication forms, patient registries, and quality-improvement methods.

Gain an understanding of the scientific literature on the essentials of diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric illness in medically ill individuals.

Find opportunities to develop relationships with primary care physicians. If you are not already a member, research and then join professional organizations most useful to your practice, such as local and national medical societies.

Use resources of the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA), including study of the Patient-Centered Specialty Practice concept. Six standards have been identified by the NCQA as essential for a practice to function in the new health care environment. These are to track and coordinate referrals, provide access and communication, identify and coordinate patient populations, plan and manage care, track and coordinate care, and measure and improve performance. They are posted at http://www.ncqa.org/Programs/Recognition/PatientCenteredSpecialtyPracticeRecognition.aspx.

Those are among the conclusions presented in the “Physician’s Accountable Care Tool Kit” released this year by the Toward Accountable Care Consortium of North Carolina, a project of the North Carolina Medical Society Foundation. The consortium includes the North Carolina Psychiatric Association (NCPA) and more than 40 other state and county medical specialty societies. The tool kit includes a section specifically for psychiatrists, drafted by NCPA’s Health Delivery System Committee.

In the movement toward integrated care, the ACO might be called the ultimate player—a multidisciplinary system built around the principles of collaborative care and on financial rewards based on cost savings and performance against quality measures. The ACO model is part of “shared savings” demonstration projects of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, and it is central in the market-based initiatives of the Affordable Care Act.

But it is also a model that may still be a mystery—too new, too big, too different—for many psychiatrists and other physicians. So the North Carolina tool kit can be regarded as a kind of “user manual” for the uninitiated, covering virtually every aspect of ACOs—purpose, structure, function, reimbursement—along with a step-by-step guide to forming or becoming part of an ACO.

The 15-page special section for psychiatrists describes recommended approaches for creating an ACO; psychiatry’s ability to add value to ACOs, with examples of high-value psychiatric interventions in the management of general medical conditions; the role of the psychiatrist as leader of an ACO; examples of existing ACO initiatives that involve psychiatrists; the importance of data on cost, quality, and outcome; and ensuring that savings achieved by ACOs are fairly and equitably distributed to participating providers (see box).

Psychiatrist Michael Zarzar, M.D., chair of the NCPA Health Delivery System Committee, told Psychiatric News that NCPA was among the first of the specialty groups in North Carolina to recognize the importance of collaboration with primary care and to begin building bridges to integrated care. And he says the tool kit project can be a model for how other APA district branches can help members navigate the accountable care movement.

“Many in primary care are increasingly aware of the value that psychiatry can bring to quality and cost control,” Zarzar said. “State and local psychiatric societies should begin to form working relationships with state medical societies, if they haven’t already. The tighter those relationships are, the better.”

APA’s district branches have an important role in helping educate psychiatrists about integrated and collaborative care and the system models that have evolved to achieve it. “It’s important that psychiatrists know these changes are coming and be prepared for them,” Zarzar said. “The better prepared we are, the more effective we can be in seizing the opportunities that the accountable care model offers.”

The tool kit emphasizes the value that psychiatry can add to ACOs. “The inclusion of the psychiatrist in the ACO team follows from data about the prevalence of psychiatric disease and psychiatric comorbidity with other illness, most commonly cardio-respiratory and metabolic disease,” according to the tool kit.

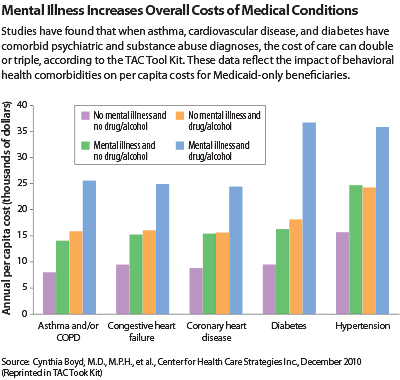

The kit cites work by psychiatrist Benjamin Druss, M.D., who has written that comorbidity “is the rule rather than the exception” in high-cost cases. “Studies have found that when asthma, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes have comorbid psychiatric and substance abuse diagnoses, the cost of such care can double or triple” (see chart).

Psychiatrist Drew Bridges, M.D., a past president of NCPA and a member of the committee that wrote the tool kit’s section on psychiatry, says NCPA has a history dating back almost a decade of building bridges with medical colleagues. In 2005, an Access to Care Committee (later renamed the Health Delivery System Committee) was formed; one of the committee’s first activities was to develop, along with the North Carolina Academy of Family Physicians, a treatment algorithm for management of anxiety disorders in the primary care setting.

More recently, the committee produced a guide to integrated care that is available to members on the NCPA website.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, Bridges emphasized a point that is evident throughout the tool kit: that the system changes inherent in the accountable care movement are inevitable and inexorable. “This is the wave of the future,” he said. “We are leaving fee for service for some kind of new payment system that rewards value, and I believe we are really on the cusp of a remarkable change in the way psychiatrists are going to be working.”

It will be a different world, but one that psychiatrists can master and in which they can be leaders. Bridges pointed out that this new way of working is not unlike the training that psychiatrists get in consultation-liaison practice within a hospital setting. “I think we can embrace those principles in a larger setting,” Bridges said.

Bridges says one issue that always arises for psychiatrists is liability and how psychiatrists will be covered for “curbside consultations”—the kind of consultations a psychiatrist in an integrated system will typically be providing to primary care colleagues. “The insurance companies have a culture change to make too,” Bridges said. “Some of them do and some don’t cover you for curbside consultations. For them, it’s all about assessing risk. But in time I think it’s a change they will make.”

He said a new initiative of the Health System Delivery Committee will be to engage with malpractice carriers on this issue. “They need to cover what is going on in the real world,” Bridges said.

The NCPA tool kit is posted at http://www.ncpsychiatry.org/assets/docs/accountable%20care%20organization%20toolkit%20final.pdf.