Some Need Extraordinary Measures When Extreme Cold Strikes

Abstract

More effort and resources need to be expended to help homeless people with mental illness find shelter from extreme winter cold.

When the polar vortex swept down across the United States in January, small groups of social workers, mental health professionals, police officers, and volunteers scurried down America’s frozen streets looking for people who didn’t want to come in from the cold.

The cold struck cities north and south. In Lexington, Ky., the daylong search for one homeless woman made headlines but ended happily when she was persuaded to sleep indoors.

Minnesota may have more experience dealing with cold weather, but this year was exceptional.

“It’s not unusual to hit 20 below here, but at times temperatures dropped to 35 below zero with wind chills at 70 below,” said Mikkel Beckmen, director of the Office of Homelessness in Minneapolis and Hennepin County. However, the combined city-county system is ready regardless of the weather or the time of year.

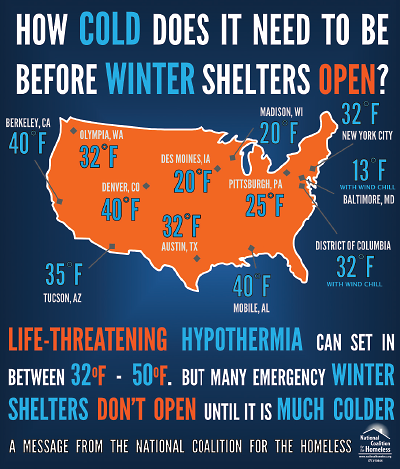

There is no standard cutoff temperature for extended opening hours for homeless shelters in winter, according to the National Coalition for the Homeless.

“We have a right-to-shelter policy,” said Beckmen. The system guarantees shelter space to all families in need, currently between 320 and 350 families. It also serves 1,000 single adults and recently opened space for 60 homeless youth.

Homeless people with mental illness fall into one of 16 categories of “disabled” people who can stay in a shelter 24 hours and get three meals a day. They also receive services intended to get them out of shelters and into housing, said Beckmen.

In Washington, D.C., workers from the Department of Behavioral Health fanned out to check on the most vulnerable of the city’s homeless, including some with mental illnesses.

“We told people they simply had to get off the streets,” said Jonathan Ward, M.S.W., director of the mobile crisis and homeless outreach programs.

The city offered alternatives to the usual shelters, which many homeless people avoid, considering them unsafe or too restrictive.

“D.C. did a stellar job using their outreach units and keeping shelters open,” said Michael Stoops, director of community organizing for the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH), in Washington. Stoops has not always seen eye to eye with the District’s homeless policies but had only praise for the creative thinking displayed during the extreme cold.

“The innovative use of warming buses, kept running 24 hours a day, saved lives,” he said. The District encouraged homeless people to park their shopping carts next to the five buses and even placed portable toilets nearby.

Technical, legal, and ethical questions hover over when and how homeless people with mental illness can be persuaded—or required—to get off the streets.

For one thing, some jurisdictions have no set cutoff temperature for expanding severe weather services. These “Code Blue” temperatures vary. The most common threshold is 32 degrees (F), but it can vary from 40 degrees to -10 degrees. Lower-temperature cutoffs may seem heartless, but they result from insufficient funding or volunteers, which limit shelter hours, except in the most extreme conditions, said Stoops.

These Code Blue temperatures “are not based on any medical or scientific criteria,” he said. “If someone is poorly clothed or is in bad health or has been drinking alcohol, temperatures in the 30s and 40s can be harmful.”

Four years ago, Lloyd Sederer, M.D., now the medical director of the New York State Office of Mental Health, recounted in the Huffington Post how, as mental health commissioner of New York City, he had spent several post-midnight hours standing in the cold with four police officers, two emergency medical technicians (EMTs), and three outreach workers trying to persuade one homeless woman to leave the stone steps of a church and spend the night in a shelter.

It was a “Code Blue” night, when city law requires police to offer shelter to people on the streets when the temperature falls below freezing and to bring them to shelter if they refuse, wrote Sederer.

And refuse the woman did, adamantly.

“The irony of the moment did not escape me since we had to remove her to safety precisely because she did not look well, nor competent to make decisions, or likely able to endure the night,” recalled Sederer. The police and the EMTs were also hesitant to control or remove the woman, fearing they would be blamed if she were injured or went into cardiac arrest. Eventually, they gathered her possessions and placed them in the waiting ambulance. They kept talking to her, and she did not resist their assistance as they moved her to the emergency vehicle and onto a nearby hospital.

“As I drove home that night, I thought, what does it take to get something done?” wrote Sederer. “Look at the time and resources it took to bring into safety one terribly endangered older woman on a hostile winter night. That experience helped me understand the kinds of judgments that sometimes are made during Code Blue nights (and other potentially deadly days and nights in New York City) that limit the protection from danger our city’s most vulnerable residents can receive. The best solution, I think, is not better enforcement of Code Blue (though that would be a good idea). It is doing everything possible to keep moments like these from happening in the first place. We have to get people off the streets before they and the weather reach the gravity of conditions we saw that night.”

“What Does It Take to Get Something Done?” by Lloyd Sederer, M.D., is posted here.

In fact, the worst conditions may not simply be the coldest, according to a 2010 NCH report on winter homeless services. People may be at serious risk when daytime temperatures are in the 40s or 50s but then drop at night into the 30s.

Those hazy boundaries raise legal and ethical questions, said Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, M.D., M.P.H., chief medical officer of the District of Columbia Department of Behavioral Health.

“When does it become so dangerous that you lower your threshold for an involuntary evaluation in an emergency room for up to 48 hours?” she said. “We decided in January that we faced a life-or-death situation. If in doubt, we want to bring somebody in and do an evaluation.”

Civil commitment was not needed to get someone out of the cold. “Anyway, “ she said, “we’d rather be sued for putting someone in the ER for 12 hours than for having them die on the streets and not doing anything.”

“This was a combined effort with D.C.’s Homeland Security and Emergency Management Agency, the Metropolitan Police, and the Department of Health,” said Stephen Baron, M.S.W., acting director of the Department of Behavioral Health and Ritchie’s supervisor. “The most important thing is to think and plan in advance, have additional resources, and make sure communications are up and running.”

The NCH recommends that expanded winter services include extending shelter hours from the usual dusk-to-dawn operation to a 24-hour-a-day model, opening up additional spaces for shelter use, and adding beds or cots in existing spaces.

“The problem with winter overflow shelters is especially acute for people with mental illnesses because those shelters don’t come with services or case managers, so people leave in the same predicament they arrived in,” said Stoops. “Trained mental health professionals should be on outreach teams to decide about placing the person in a psychiatric facility for the night.”

Psychiatrists should prepare in advance of cold-weather emergencies, said Ritchie. “You’re going to be asked what to do, so look at legal standards for involuntary detention in advance and see what kind of room they give you in extraordinary weather circumstances,” she said. “Then work it out with the police to have the same standards.” ■

The National Coalition for the Homeless’s report on winter homeless services is posted here.