High Court Weighs Standards for Intellectual Disability

Abstract

The Supreme Court wants to know if a convicted murderer’s cognitive abilities can be encapsulated in a single number that makes him eligible for the death penalty.

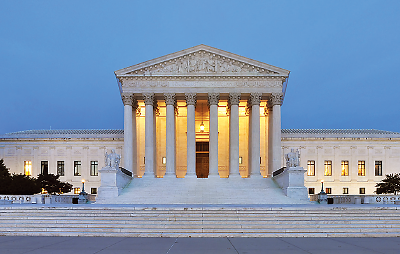

The U.S. Supreme Court hears arguments on the standards states adopt to determine if a murderer is eligible to be executed.

Just how intellectually disabled must a convicted murderer be before the state is barred from executing him?

That might seem like a complex question to a psychiatrist, but Supreme Court justices spent most of their time one cold March morning asking not about the man who spent 35 years on Florida’s death row but about statistical aspects of his IQ tests.

Freddie Lee Hall was convicted of the rape and murder of a 21-year-old woman in 1978. In a prior case, Atkins v. Virginia, in 2002, the Supreme Court held that executing a mentally retarded (now termed “intellectually disabled”) person violated the Eighth Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibits “cruel and unusual punishments.”

The Court in Atkins left it up to the states to determine standards for intellectual disability. Florida set the bar at an IQ of 70, along with deficits in adaptive behavior and an onset before age 18. Hall had scored 71 or higher on several IQ tests, making him eligible for the death penalty.

Allen Winsor, Florida’s solicitor general, argued that once the prisoner scored above 70, the other two criteria became irrelevant. Furthermore, the state couldn’t have its laws governed by the subjective—and changeable—views of clinicians.

The statistical argument revolved around whether a score of 70 was a “bright line,” a number that must be adhered to inflexibly.

“Because of the standard error of measurement that is inherent in IQ tests, it is universally accepted that persons with obtained scores of 71 to 75 can, and often do, have mental retardation when those three prongs are met,” argued Hall’s attorney, Seth Waxman, at the March 10 hearing. “If a state conditions the opportunity to demonstrate mental retardation on obtained IQ test scores, it cannot ignore the measurement error that is inherent in those scores that is a statistical feature of the test instrument itself.”

APA joined with other mental health organizations in filing an amicus curiae brief with the Court on Hall’s behalf.

“We are saying that if a state relies on some definition of mental illness or intellectual disability, then that definition should reflect current research and current thinking,” said Colleen Coyle, J.D, APA’s general counsel. That definition requires more than just a pass/fail grade on an IQ test.

APA’s position calls for not only recognizing the standard error of measurement but for applying all three criteria—IQ, functionality, and age of onset—in the context of a full evaluation of the person facing execution.

“Using a single IQ score goes against how we think about intellectual disability,” said Richard Frierson, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine and director of its forensic psychiatry fellowship. Frierson was not involved in the Hall case.

“It is possible to diagnose a person with an IQ score above 70 but who has difficulties with adaptive functioning—their ability to care for themselves or live independently,” said Frierson, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

“The oral argument underscored the differing perspectives with respect to the death penalty,” said APA Treasurer David Fassler, M.D., a clinical professor of psychiatry at the University of Vermont. “A majority of the justices seemed skeptical of the limitations imposed by the current Florida law. The prevailing view was that judges and juries should have access to as much information as possible when considering whether or not a defendant is eligible for the death penalty.”

APA and other mental health organizations and advocates may have more work ahead of them, regardless of the Court’s decision, which is expected later this spring.

“We must better educate judges and lawyers about the role of adaptive functioning to remind them that this is a gray area, not one that is simply black and white,” said Frierson. “There are still so many disparities regarding persons on death row with mental illness and intellectual disability, and it will be interesting to see if the Court takes them up in the future.” ■