When APA Decides to Go to Court

Abstract

When the needs of the profession or patients demand it, APA may enter the courtroom in one of several roles.

In the American justice system, APA’s Committee on Judicial Action plays many roles, from a concerned bystander to a full participant, said speakers at APA’s annual meeting in New York in May.

In one long-running case, for example, the committee joined with other mental health organizations in an amicus curiae (“friend of the court”) brief in Hall v. Florida, a case argued in March before the U.S. Supreme Court. The brief opposed Florida’s use of a fixed IQ score of 70 to determine a convict’s eligibility for the death penalty (see page 1).

Under previous Supreme Court rulings, 18 states had barred executions for people with intellectual disabilities because, it said, “execution doesn’t contribute to goals of retribution or deterrence.”

DSM-5 uses three criteria to define intellectual disability: an IQ score below 70, deficits in adaptive functioning, and onset during development—although no specific time parameter is cited.

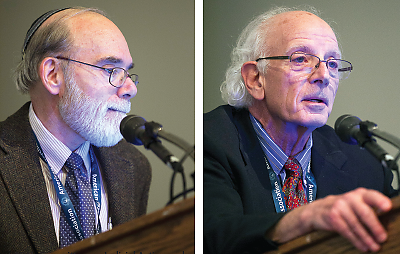

APA’s Committee on Judicial Action makes recommendations to APA leadership on court cases involving mental health, explained former APA president Paul Appelbaum, M.D. (left), and Howard Zonana, M.D., at the APA annual meeting in New York.

“However, the court did not ask about the DSM-5 definition of intellectual disability in oral arguments,” said former APA President Paul Appelbaum, M.D., the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “They were looking for a bright line and focused on the IQ test’s standard error of measurement, which has a range of plus or minus 5 points” (Psychiatric News, April 1).

The committee also provides APA district branches and state associations with substantive help in cases with important professional implications, said Yale University forensic psychiatrist Howard Zonana, M.D. In the New York state case, N.Y. v. Rivera, for example, it provided funds and a review of appellate briefs by a Washington, D.C., attorney specializing in appeals work. That case attempts to clarify whether the mandatory duty to report child abuse overrides confidentiality and attorney-client privilege when the examining psychiatrist or psychologist is hired by the defendant’s attorney.

As a practical matter, most attorneys know about the reporting law, but the status of those employed by them is at issue in the Rivera case, said Zonana.

“I tell a defendant that I will report if he reveals child abuse,” he said. “But most states have not answered the question about mandated reporting when working for a lawyer.”

In a third case, APA and others filed suit against Connecticut’s Anthem Health Plans regarding certain nonquantitative treatment limitations, which APA and the other amici say violates the Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act, said Marvin Swartz, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke University.

Quantitative limits include terms such as annual maximum payments or time limits. Nonquantitative limits include utilization reviews or requiring a visit on a different day to a second provider in order for a patient to receive psychotherapy treatment.

Anthem thus imposes “double copayments on psychiatric patients, reduces reimbursement rates for psychiatrists, creates disparities in rates between mental health and medical/surgical services, and fails to pay for psychotherapy by psychiatric physicians,” according to APA’s complaint. This case is still in the Connecticut courts (Psychiatric News, April 5, 2013).

Such active roles have to be carefully chosen for their wider impact on the profession and patients. “Being a party to a case is very expensive and thus limits the number of cases APA can pursue,” Swartz explained. But the ability to have APA’s voice heard “is important for patients.” ■