More Clinical Focus Needed on Youth With DMDD

Abstract

Youth who erupt with anger on a regular basis are at heightened risk for an anxiety or depressive disorder as young adults, but anxiety or depression treatment at an early age might head off many of their problems.

The outlook for youngsters who are persistently irritable and who frequently erupt in anger is “bleak,” a new study published April 29 in AJP in Advance has found.

The study was conducted by researchers at Duke University and the University of North Carolina. The lead researcher was William Copeland, Ph.D., an assistant clinical professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Duke.

In 1992, researchers involved in the current study launched the Great Smoky Mountains Study to evaluate the mental health of children living in the western Smoky Mountains region of North Carolina and followed participants’ mental and physical health as they grew up. The participants lived in either rural or urban areas, and many of the youth were Native Americans, a minority that has been underrepresented in mental health studies.

Persistent irritability punctuated by frequent temper outbursts is a hallmark of disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD). Although DMDD was only officially recognized with the publication of DSM-5, its criteria overlap with those of oppositional defiant disorder and depression. Thus the researchers decided to use mental health interview results from 1,420 Great Smoky Mountains Study subjects when they were aged 10 to 16 to ascertain how many of the subjects would have met criteria for DMDD at those ages.

About 4 percent of the subjects would have met the criteria, the researchers learned.

They then compared the outcomes from the subjects when they were aged 19 to 25 who would have met criteria for DMDD as children with the outcomes at ages 19 to 25 of subjects who would not have met DMDD criteria.

Subjects who would have met the DMDD criteria were significantly more likely to have a depressive or anxiety disorder as young adults than were subjects who as children had had no mental disorders and subjects who as children had had other types of mental disorders.

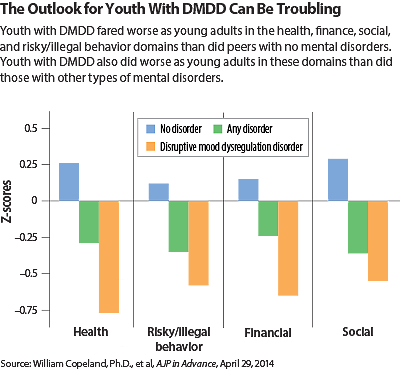

In addition, subjects who would have met the DMDD criteria as children were significantly more likely as young adults to have experienced a serious illness, a sexually transmitted disease, police contact, physical fighting, felony charges such as breaking and entering, low educational attainment, violent relationships, social isolation, and impoverishment than subjects who had not had any mental disorders during childhood.

And subjects who would have met DMDD criteria as children were significantly more likely to experience serious illness, sexually transmitted disease, police contact, low education, and impoverishment than were subjects who had other types of mental disorders as youth.

Thus, “The long-term prognosis of children with DMDD is one of pervasive impaired functioning that, in many cases, is worse than that of other childhood psychiatric disorders,” the researchers said in their report. “Our analysis suggests that this bleak prognosis includes increased health problems, continued emotional distress, financial strain, and social isolation. For most children, development provides a constant series of opportunities for recovery and rehabilitation, but for children with DMDD, the accumulation of early failures may perpetuate a lifetime of limited opportunity and compromised well-being. As such, children with persistent irritable mood punctuated by frequent outbursts—regardless of what we call this cluster of symptoms—should be a priority for clinical care and treatment development.”

Commenting on the study for Psychiatric News, Ellen Leibenluft, M.D., chief of the Section on Bipolar Spectrum Disorders at the National Institute of Mental Health and an expert on DMDD, said, “What we learn is that children with DMDD are at increased risk for anxiety and depression when they grow up. The fact that they are at risk for anxiety and depression is consistent with research looking at outcomes for irritability generally. But it is helpful to have the finding confirmed in a sample in which the researchers explicitly applied criteria for DMDD.”

“Particularly interesting about this study,” she added, “is how it demonstrates the severe impairment that children with DMDD experience as adults, even when compared with children who have other psychiatric disorders. We already knew how impairing the condition was in children. Now we know that it continues to have long-term adverse consequences as well.”

The challenge now, Leibenluft continued, is to determine whether first-line treatments for anxiety or depressive disorders, such as SRI antidepressants or cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), can help children with DMDD. “Actually we are conducting a clinical trial at NIMH to answer this question.”

“But until the answer is in, clinicians should feel comfortable about using SRIs or CBT to treat children with DMDD and comorbid anxiety or depressive disorders,” she said. “SRIs, of course, are relatively contraindicated in children who have bipolar disorder, but the psychiatric literature suggests that DMDD is not a strong predictor of bipolar disorder.”

The study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, the Brain and Behavior Research Foundation, and the William T. Grant Foundation. ■

An abstract of “Adult Diagnostic and Functional Outcomes of DSM-5 Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder” can be accessed here.