Summit Conference Addresses MH Issues in Troubled City

Abstract

Beset by economic distress, crime, and unemployment, Detroit residents will benefit from the commitment of several groups to enhance treatment access and mental health education and battle stigma.

A metonym for the nation’s automobile industry, Detroit was a mecca for job opportunity for many Americans during the mid-20th century. Home to more than 1.8 million residents in the 1950s, it was the fifth largest U.S. city. In the 1960s it gained more fame as the birthplace of the Motown music empire that had many Americans “Dancing in the Streets.” Now, just a few decades later, the city is bankrupt, with 60 percent fewer people than it had in 1950 and stricken with a plague of abandoned buildings, high crime rates, and sky-high unemployment.

In June, APA’s Division of Diversity and Health Equity (DDHE)—formerly known as the Office of Minority and National Affairs (OMNA)—in partnership with the Community Network Services (CNS) in Detroit held a leadership summit to discuss ways to extend mental health services to residents of areas that are heavily impacted by the city’s economic collapse.

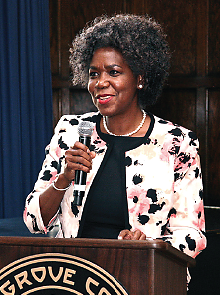

Community Network Services Medical Director Michele Reid, M.D., and President Michael Garrett pose at the mental health leadership conference in Detroit co-sponsored by APA.

The idea for the summit was generated from a previous OMNA-on-Tour event concerning the mental health consequences of areas hit by natural disasters. “APA saw the economic disaster of Detroit and decided to add the city to the tour list,” explained psychiatrist Michele Reid, M.D., medical director of CNS, in welcoming participants to the summit. “They gave me a call, and I told them to come on—we are more than ready to work with you.”

During the first decade of the 21st century, Detroit experienced economic calamity as a result of the financial downturn of the automobile industry and extensive municipal corruption. The Department of Labor reported a 9 percent unemployment rate for the Detroit metropolitan area in April. With a poverty level almost three times higher than the U.S. average, Detroit has topped the Forbes magazine list of the most dangerous American cities for five consecutive years. Accompanying that crisis is a heroin-use prevalence that is double that of the rest of the nation.

APA Deputy Medical Director Annelle Primm, M.D., M.P.H., says it is important to extend mental health services to residents of distressed areas.

“There is a vicious cycle that is associated with poverty and mental distress,” said APA Deputy Medical Director and DDHE Director Annelle Primm, M.D., M.P.H., who spoke at the summit. “Social environments and socioeconomic status, along with other factors, are determinants that can greatly affect one’s mental health,” Primm emphasized. “Unmet mental health needs can compromise overall general health, leading to drug and alcohol addiction, increased risk for chronic diseases, and homelessness,” she explained. “If we can address mental health needs early, it can help eliminate a cascade of adverse events.”

The summit, held at Marygrove College in the city’s northwest section, included discussions led by psychiatrists, mental health professionals, academic leaders, law enforcement personnel, and politicians, all of whom are committed to implementing actions to help revitalize the city through making mental health services more accessible.

Policy related to mental health was a key issue for conference participants. “Policy is how we are able to achieve goals in the community sector,” said Reneé Canady, Ph.D., M.P.H., CEO of the Michigan Public Health Institute. “It’s about activity—not just admiring a problem or writing about a problem, but really focusing on how we will intervene in that problem.” In a later interview with Psychiatric News, Canady said that rather than just addressing symptoms associated with mental disorders, it is important to address the factors that may contribute to or cause one to overlook symptoms of an undiagnosed psychiatric disorder, such as being thrown into the criminal justice system, lack of education about mental illness, and unemployment.

For mental health professionals to be effective in public policy, Canady emphasized, they must learn how to gain support from legislators when issues directly or indirectly touching on mental health arise—a strategy that seems to be working in Michigan.

Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.) explains the importance of the Excellence in Mental Health Act in the potential expansion of mental services to many more residents of Michigan.

“Now is the time to push the issue of mental health in Detroit,” urged Sen. Debbie Stabenow (D-Mich.). A fervent advocate of issues concerning mental health care, Stabenow is advocating to have Michigan be one of eight states selected to receive $25 million for a two-year pilot program as part of the Excellence in Mental Health Act, which is intended to increase access to community mental health and substance use treatment services while improving Medicaid reimbursement for these services.

“Accessibility to mental health care gives hope to people with mental illness that they can live healthy and productive lives. We must continue to fight,” exclaimed Stabenow, who along with Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) introduced the bill, which President Obama signed into law April 1.

Other topics discussed during the conference included strategies to reduce stigma and the importance of peer counselors in reaching some people with mental health problems.

“I love being a role model,” said Malkia Newman, a presenter at the summit and a peer educator at CNS. Newman spoke about her struggle with bipolar disorder—an illness that she was unaware she had for more than 30 years. “When I was having a manic episode or ‘up,’ I thought it was my personality to be extremely bubbly,” she explained to Psychiatric News. “But when I came down from it, I crashed [into depression].”

Because of her long struggle with bipolar disorder, which is now well managed, Newman said, “I feel like it is my responsibility to speak for those who cannot speak for themselves and impact the lives of people in situations similar to those which I experienced.”

Near the end of the meeting, many of the participating organizations pledged to implement specific actions they hope will increase the effectiveness of mental health services within the city. Detroit Recovery Project committed to putting more people out front who have recovered from substance use disorders and mental illness, and CNS committed to educating organizations, such as churches and schools, on issues that relate to mental health.

“This was a very outcomes-focused program,” Primm noted. “Leaders from all disciplines and sectors sat down and shared stories in order to get a unified commitment to carry out actions that will benefit the residents of Detroit. I’m confident that great things will come out of this summit.” ■