Journal Digest

Abstract

Video-Based Therapy Improves Engagement in Babies at Risk for ASD

While symptoms of autism may not become manifest in children until they reach age 3 or 4, several risk markers—such as inattention or disengagement—may be present during the first year.

As published in Lancet Psychiatry, a video-based family therapy can improve these social behaviors in infants at risk for autism, which might help reduce or even prevent autism symptoms in childhood.

The program is known as Video Interaction for Promoting Positive Parenting (iBasis-VIPP) and uses video-feedback sessions to help parents understand and adapt to their infant’s individual communication style.

Fifty-four families with infants aged 7 to 10 months were randomly assigned to receive iBasis-VIPP or no intervention over a five-month period; all the infants chosen had an older sibling diagnosed with autism, thus increasing their risk. Families receiving the video therapy showed improvements in infant attention, engagement, and social behavior; the parents also improved by being less directive in their interactions.

Green J, Charman T, Pickles A, et al. Parent-mediated intervention versus no intervention for infants at high risk of autism: a parallel, single-blind, randomised trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015 Feb; 2(2):133-140.

Researchers Solve 3D Structures of Valium-Binding Protein

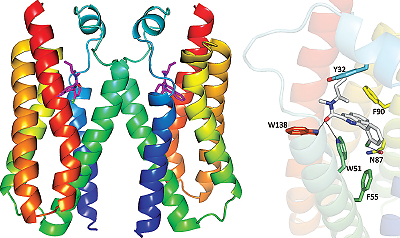

Translocator protein (TSPO) is a protein found on the mitochondria that can bind cholesterol and other molecules. Those other molecules include benzodiazepines like Valium, which suggests that TSPO might contribute to Valium’s side effects.

The new 3D structures of the Valium-binding translocator protein (TSPO) might provide key molecular details to help develop improved medications.

Two teams of scientists have solved the three-dimensional atomic structure of TSPO in various conformations, which could provide key architectural details to develop improved psychiatric drugs.

One team, led by researchers at Columbia University and Brookhaven National Laboratory, developed structures of TSPO both in a natural state and bound with a Valium mimic; they also carried out biochemical assays to provide more insight into what TSPO does in a cell.

They found that TSPO can break down a hemelike molecule in red blood cells to create a compound they termed bilindigin; while the function of bilindigin is unknown, it bears close resemblance to a chemical that scavenges free radicals, suggesting a role for TSPO in controlling the cellular levels of reactive oxygen.

Meanwhile, researchers at Michigan State University solved a structure of a TSPO mutation associated with some cases of bipolar disorder (Ala/Thr 147). They found that one small change causes TSPO to bind cholesterol less strongly, providing insight into the physiology underlying some mood disorders.

These two studies were published concurrently in Science.

Guo Y, Kalathur R, Liu Q, et al. Structure and activity of tryptophan-rich TSPO proteins. Science. Jan 30, 2015; 347(6221):551-5. Li F, Liu J, Zheng Y, et al. Crystal structures of translocator protein (TSPO) and mutant mimic of a human polymorphism. Science. Jan 30, 2015; 347(6221):555-8.

Anorexia Induces Epigenetic Changes Over Time

Behaviors associated with eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa (AN) can become more difficult to break over time. New work appearing in the International Journal of Eating Disorders has identified biological changes that may underlie this entrenchment.

A genomic analysis of women with AN and matched controls found that the chronicity of the eating disorder correlated with the degree of changes in DNA methylation—a chemical modification that affects gene expression—involving genes associated with anxiety, social behavior, immunity, and the functioning of the brain and peripheral organs. The longer the illness, the more pronounced the methylation differences.

These findings provide clues about the physical mechanisms that contribute to the emotional and psychological symptoms observed in people with AN. They also reaffirm the importance of identifying and treating patients with AN as soon as possible.

The research group will next explore whether remission of AN corresponds to a restoration of proper DNA methylation levels; the relationship between methylation and disease symptoms may help uncover new treatment strategies, the authors noted.

Booij L, Casey K E, Antunes J M, at al. (in press). DNA methylation in individuals with anorexia nervosa and in matched normal-eater controls: A genome-wide study. International Journal of Eating Disorders. DOI: 10.1002/eat.22374/

Psychopathic Offenders’ Brains Can’t Learn From Punishment

Criminal offenders with a diagnosis of psychopathy have higher rates of recidivism compared with other offenders. To improve rehabilitation potential, it’s important to understand why.

An MRI analysis carried out by researchers in Canada and England suggests that abnormalities in key brain regions related to empathy, moral reasoning, and learning from rewards and punishment may explain these psychopathic tendencies.

The researchers analyzed data on 12 violent offenders with antisocial personality disorder and psychopathy (participants who scored 25 or higher on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised [PCL-R] test), 20 violent offenders with antisocial personality disorder but no psychopathy, and 18 healthy nonoffenders. The volunteers completed an image-matching game that assessed their behavior when the game’s consequences switched from positive to negative.

The offenders with both antisocial disorder and psychopathy showed increased activation in discrete brain regions in response to punished errors but decreased activation to all correct rewarded responses.

“Offenders with psychopathy may consider only the possible positive consequences and fail to take account of the likely negative consequences [when making decisions],” explained author Sheilagh Hodgins of the Universitȳ de Montrȳal. “Consequently, their behavior often leads to punishment rather than reward as they had expected.”

This study appeared in Lancet Psychiatry.

Gregory S, Blair R, Ffytche D, et al. Punishment and the psychopath: an fMRI investigation of reinforcement learning in violent antisocial personality disordered men. Lancet Psychiatry. Feb 2015; 2(2):153-160.

Low Serotonin May Lead to Lack of Responsiveness to SSRIs

Researchers may have discovered a clue as to why some people with depression are unresponsive to treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), one of the most common antidepressant pharmacotherapies.

After exposing two mouse models to seven days of psychosocial stressors, genetic researchers from the Duke Institute for Brain Sciences observed that mice that were genetically deficient in serotonin were more vulnerable to displaying depression-like behaviors than their littermates with normal serotonin levels. Though longer exposures to stress led to depression-like behaviors in both groups, serotonin-deficient mice were unresponsive to treatment with a common antidepressant, fluoxetine. However, the researchers were able to alleviate treatment “depression” in serotonin-deficient mice by inhibiting hyperactivity of the lateral habenula, a region that may be involved in depression onset.

The researchers noted that since SSRIs work by blocking the ability of neurons to recapture serotonin, it makes sense that such antidepressants would be less effective in animals with already low levels of serotonin. “The next step,” said lead author Benjamin Sachs, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow, “is to figure out how we can turn off the [lateral habenula] brain region in a relatively noninvasive way that would have better therapeutic potential.” ■

Sachs B, Ni J, Caron M. Brain 5-HT deficiency increases stress vulnerability and impairs antidepressant responses following psychosocial stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. February 9, 2015. [Epub ahead of print]