Researchers Consider Infection as One Cause of Depression

Abstract

Inflammatory reactions to bacteria or viruses may be key to the so-called “spread” of depression.

Could major depressive disorder be the outcome of an infectious disease?

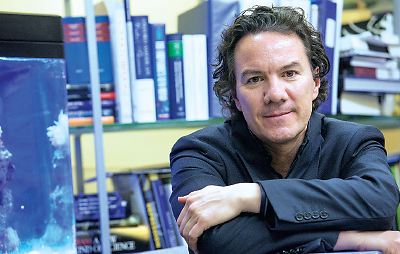

Considering that possibility might well open new approaches to understanding, preventing, and treating the disorder, according to Turhan Canli, Ph.D., an associate professor of integrative neuroscience in the Department of Psychology at Stony Brook University in New York.

Turhan Canli, Ph.D., hypothesizes that there is a variety of infectious pathogens that affect the central nervous system and may lead to depression.

His approach is “deliberately speculative” but warrants attention and action, wrote Canli in the online October 2014 Biology of Mood and Anxiety Disorders. “I propose that future research should conduct a concerted search for parasites, bacteria, or viruses that may play a causal role in the etiology of MDD.”

Canli offers several arguments to support his point.

Patients with depression exhibit sickness behavior. Also, depression is significantly associated with infectious agents, including viruses like Borna disease virus, herpes simplex virus-1, varicella zoster, and Epstein-Barr virus. Parasites like Toxoplasma gondii may play a role.

“Among patients with diagnosed major depression or bipolar disorder, those with a history of suicide attempt had higher Toxoplasma gondii antibody titers,” he said.

Could Intestinal Tract Be Involved?

Another possibility is the “leaky gut” hypothesis, suggesting that cytokines increase intestinal-tract permeability to lipopolysaccherides (LPS) from gram negative bacteria and that antibodies to the LPS are found at higher levels in depressed patients.

Even a study of exogenous retroviral sequences might be useful, given that “the search for genes linked to major depression has come up empty.”

Nevertheless, Canli is not yet ready to identify a specific infectious agent that causes depression.

“I suspect that there is a wide variety of infectious agents out there that affect the central nervous system in their own way,” he told Psychiatric News. “I also don’t think that every case of depression is caused by an infectious agent. But given its prevalence, even a subset of patients would still add up to a large number of cases.”

Role of Prenatal Infection Investigated

The literature on postnatal infection and risk of depression is sparse, commented Alan Brown, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University Medical Center, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, and the Joseph L. Mailman School of Public Health. Brown has studied the effects of prenatal infection, as recorded in maternal antibodies, as risk factors for mental illness.

As far as he knows, there have been no studies on how rates of depression might correlate with disease outbreaks, although geographic variations in suicide have been observed, said Brown.

“However, there are multiple factors apart from infection that can influence these findings, and they are vulnerable to biases from the ecologic fallacy—correlations in populations may not reflect correlations within individuals,” he said.

Infectious agents have been known to affect the brain and cause psychiatric disorders. Syphilis helped fill America’s mental asylums in the late 19th century, for instance.

However, most infections that lead to behavioral changes don’t do so by directly infecting the brain, said Andrew Miller, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at Emory School of Medicine and an expert on brain-immune interactions. “We can’t seem to find an agent that’s reliably associated with psychiatric disorders that is not also found in healthy persons.”

The key may be not disease but the inflammatory reaction caused by disease, whatever its cause, given that higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines are found in people with depression. Another recent report, drawing on data from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children in Great Britain, found that children with the highest levels of the systemic inflammatory marker IL-6 at age 9 were more likely to be depressed at age 18 (odds ratio=1.55), wrote Golam Khandaker, M.B.B.S., Ph.D., a clinical research fellow in psychiatry at the University of Cambridge, and colleagues in the October 2014 JAMA Psychiatry.

“There are many roads to inflammation and its effects on the brain,” said Miller in an interview. “Inflammatory cytokines and activated cells that produce cytokines all get into the brain and ultimately interact with various neurocircuits, leading to prototypical behavioral responses that we see in infection. This can result in anhedonia or loss of motivation but also, paradoxically, anxiety and arousal.”

When used as therapy for hepatitis-C or cancer, cytokines such as IL-2, IFN-α, or TNF-α appear to induce depressive and flu-like symptoms. “This is where my thinking appears to deviate from others’,” said Canli. “Does generic inflammation account for the neural structural and functional phenotypes we see in depression? No. Is it plausible that there are pathogens that do? Absolutely.”

He cites as an example the ability of T. gondii to form cysts in the hippocampus and amygdala of infected rodents.

“Who knows what other pathogens may exist that possess similar mechanisms?” he said. “Interventions that target only the immune response may bring symptom relief but would not address the root cause of the illness.”

Canli suggested that the next step in testing his hypothesis should be large-scale studies of well-characterized patients and controls.

“The way to proceed is to search for evidence of infectious pathogens in tissue, fluid, or postmortem brain samples from depressed patients and compare those against healthy controls,” said Canli. “There are molecular protocols that allow both the detection of known and the discovery of unknown pathogens. If such pathogens were discovered to be associated with depression, the hard work would begin to determine causality.”

While his arguments may be plausible, cross-sectional studies may not provide the answers he seeks, cautioned Brown.

“The potential flaw here is reverse causality,” he said. “Depression itself can affect the immune system, increasing vulnerability to depression and confounding results.”

Miller advocated a step-by-step approach, first establishing that inflammation contributes significantly to a subset of depression. “Then we can look at where the inflammation is coming from and how we can stop it other than directly blocking it,” he said. ■

“Reconceptualizing Major Depressive Disorder as an Infectious Disease” can be accessed here.