Mayo Program Teaches Residents to Empathize With Suicidal Patients

Abstract

The heart of the training is the case formulation, in which residents are challenged to write a description of a patient at risk for suicide that captures more than the descriptive facts necessary for the medical record.

Suicide is usually a solitary act, almost always attempted in isolation and in a state of mind that can be difficult or impossible to fathom for survivors and caregivers—including physicians and psychiatrists.

While psychiatry trainees will invariably learn how to assess for and document suicidal risk, teaching them how to empathize with the subjective state of the suicidal patient is another matter.

But that’s the goal of a new didactic and case formulation seminar on assessment of suicidal risk for psychiatry residents at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine in Rochester, Minn. The seminar, which provides trainees a biopsychosocial context for understanding the individual patient’s subjective state of anguish and despair, was developed and taught by Michael Bostwick, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at Mayo. The course is part of a 10-week case formulation curriculum for PGY-2, -3, and -4 residents at Mayo.

At the heart of the training is the case formulation, in which residents are challenged to write a description of an at-risk patient that captures more than the descriptive facts necessary for the medical record, but that illustrates an understanding of the individual’s narrative that has brought them to a suicidal crisis.

Two Formulations, One Patient

Below are two case formulations written by a psychiatry resident before and after the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine’s course on biopsychosocial assessment of suicidal risk.

Case Formulation 1

Risk factors:

Presently experiencing suicidal ideation with thoughts of using firearm

Agitated and pacing in room

Inability to consider future options, endorsing being overwhelmed and hopeless

Presently depressed

History of overdose one year ago

Strong character traits of impulsivity

Access to firearm collection with ammunition

Protective factors:

Family with three children stable and mutually identified “good” marriage

Strong community connections with supportive family

No evidence of substance use

Access to care

Case Formulation 2

Ms. X has a recent history of a suicide attempt by medication overdose for which she received psychiatric hospitalization (including ECT and medication changes). She tells me that she did intend to die. She says that her feelings regarding suicide at this time are mixed—she is grateful not to be dead but is somewhat ambivalent about life in general and has had moments where she wishes she was dead. … At this time there is no perturbation or change in her levels of stress or her pain. She does not feel that a return to the hospital would be helpful, and I would agree as hospitalization will not change fundamentally the chronic stressors she faces. She has developed a better crisis plan and is thinking of more ways to manage stress and cope. She remains at heightened risk for suicide by virtue of her underlying stressors, recent attempt, emotional dysregulation, and impulsivity. She is protected, at this time, by her increased hope for the future. … She continues to identify her children as a source of strength and desire to live. She has access to care at the clinic and is actively looking at medications that may assist her in being more successful and safe.

“The idea is that if you can really understand the subjective experience of the suicidal patient, it can guide the development of a treatment plan tailored to help that particular patient,” said Brian Palmer, M.D., vice chair of education and an assistant professor of psychiatry at Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, in an interview with Psychiatric News.

Palmer developed the 10-week formulation course and presented the suicide portion in the workshop “Preparing Residents for Therapeutic Work With Suicidal Patients: Curriculum Elements That Foster Competence and Collaboration,” presented at the March meeting of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training (AADPRT) in Orlando, Fla. He was joined in the workshop by Liza Donlon, M.D., and Alex Sabo, M.D., of Berkshire Medical Center in Pittsfield, Mass.

In an interview after the AADPRT meeting, Palmer said nearly one-third of all psychiatric residents will experience the suicide of a patient. “For some trainees it can be professionally traumatizing,” he said, “causing them to question their choice of psychiatry as a specialty. People respond in different ways—some feel responsible and guilty, believing they could have or should have done more to help, some pull back, and some of us re-double our efforts to understand our patients.”

Palmer and fellow participants in the AADPRT workshop said psychiatry residency training programs should offer both didactic and clinical experiences that teach residents suicide risk-assessment skills, how to form therapeutic relationships with suicidal patients, how to manage transference and countertransference phenomena, and how to specifically address, monitor, and document the drivers of suicidal behavior.

Palmer noted that the psychiatry milestones developed as part of the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Milestone Project address the need for graduating residents in psychiatry to be able to demonstrate skills specific to the care of suicidal patients. For instance, under the domain “Interpersonal and Communication Skills,” the psychiatry milestones call for a resident to show that he or she “develops therapeutic relationships in complicated situations,” “sustains working relationships in the face of conflict,” and “sustains therapeutic and working relationships during complex and challenging situations, including transitions of care.”

Mayo’s course on suicidal assessment is based on three underlying assumptions: each suicidal situation is unique, doctor and patient collaboratively construct a suicide “narrative,” and treatment is tailored to each unique narrative. The didactic covers biological, cognitive, and behavioral theories of suicidality; risk factors versus warning signs; psychopharmacologic treatment of depression, anxiety, psychosis, and other symptoms associated with suicidality; psychotherapy of at-risk patients; and suicide on the inpatient unit and strategies for reducing environmental risks on inpatient wards.

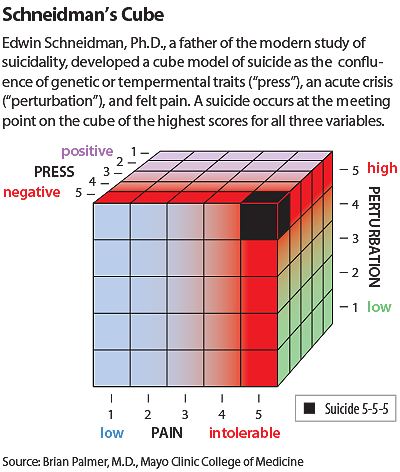

Especially crucial in conveying the biopsychosocial factors around suicide is the use of Schneidman’s Cube Model, a graphic heuristic of the suicidal crisis, as one that results from the confluence of pain, “press,” and perturbation (see graphic). “Press” refers to a predisposition or tendency toward suicidal behavior; perturbation refers to an acute event driving the suicidal crisis; and pain is the degree of emotional distress caused by the crisis, sometimes referred to as “psychache.”

At the beginning of the seminar, residents are assigned to write a case formulation about a suicidal patient they have encountered; they are also asked to write a second formulation at the end of the course. According to Palmer, the residents’ pre- and post-course formulations are strikingly different. For an example of a resident’s pre- and post-formulation about a female patient with a history of attempted suicide by overdose and ongoing psychosocial stressors, see the sidebar.

“The first formulations tend to read like a list of things the resident has learned should be in the medical record,” Palmer told Psychiatric News. “But the second formulations are richer, capturing a better sense of the individual and his or her story. It’s really daunting to allow yourself to feel how someone can be suffering so much that the patient would consider [suicide].”

But, it’s this skill that is crucial in the training of physicians who will be able to engage with and treat the “person behind the disease,” Palmer said.

“As psychiatrists, we all see suicide and suicidal patients,” he said. “One of our challenges is to avoid the reduction of our patients to risk factors and checkboxes that our medical record-keeping system requires but that can make it hard to find the person suffering in front of you. The whole purpose of the formulation course is to help our residents understand individual patients in an increasingly full way. We want to integrate the best of the current thinking about suicidality, but not in a ‘one-size-fits-all’ way.” ■