Adults With MDD Benefit From Bright Light Therapy

Abstract

Bright light therapy shows promise as an easy-to-use and inexpensive option for people with nonseasonal major depressive disorder.

Bright light therapy has been shown to be an effective treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and now a study published last month in JAMA Psychiatry shows that this therapy may also be effective for nonseasonal major depressive disorder (MDD).

Raymond Lam, M.D., says his findings suggest that light therapy should be considered as a treatment option for patients with nonseasonal depression.

“These results are very exciting because light therapy is inexpensive, easy to access and use, and comes with few side effects,” Raymond Lam, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at the University of British Columbia, told Psychiatric News. “This is one of the first studies using light to treat nonseasonal depression.”

To examine the efficacy of light treatment alone or in combination with antidepressants for the treatment of MDD, Lam and colleagues conducted an eight-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of adults aged 19 to 60.

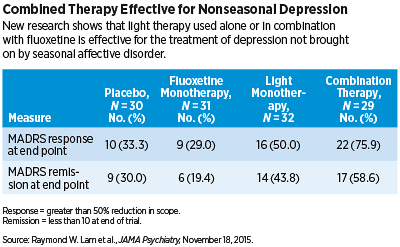

A total of 122 patients with MDD were randomly assigned to one of four groups: light therapy (active white light box for 30 minutes in the early morning plus placebo pill each day); antidepressant therapy (inactive negative ion generator plus fluoxetine hydrochloride [20 mg] each day); combined light and antidepressant treatment; or placebo (inactive negative ion generator plus placebo pill). The primary outcome measure was a reduction in score on the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) from baseline to endpoint. Secondary outcome measures included response (greater than 50 percent reduction in MADRS score) and remission (MADRS score less than 10 at the end of the trial).

The researchers found that light monotherapy and combined light-antidepressant therapy was statistically superior to placebo as it relates to a reduction in MADRS scores; there was no statistical difference between fluoxetine monotherapy and placebo. In addition, the researchers observed that approximately 50 percent and 76 percent of patients who underwent light monotherapy and combined therapy, respectively, achieved a response; 29 percent and 33 percent of individuals, respectively, treated with fluoxetine monotherapy and placebo achieved such a response. Remission was achieved by approximately 44 percent and 59 percent of those individuals receiving respective light monotherapy and combined therapy, compared with 19 percent and 30 percent achieved by those receiving fluoxetine monotherapy and placebo, respectively.

Light therapy was found to be well tolerated with few side effects. The most common adverse events associated with light monotherapy included diarrhea and increased appetite.

Lam added that light therapy remained effective at reducing symptoms of depression regardless of the time of year the therapy was administered.

“This trial represents, to our knowledge, the first adequate duration, placebo-controlled comparison of light monotherapy,” the researchers wrote. “Our randomized, double-dummy design, in which patients used a device and took a pill, controls for the nonspecific effects of light therapy or medication.”

However, Lam told Psychiatric News that many questions about the therapy remain unanswered: “For example, how long should people continue on light [therapy] after they are better? Would light work better given at different times of the day? What is the mechanism of action of light in nonseasonal depression? Is it similar or different from those considered in SAD?” he asked.

According to Lam, answering these questions may one day give clarity on the best treatment options for treating both SAD and nonseasonal MDD.

The current study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. ■