ADHD Diagnoses Climb Across Racial/Ethnic Groups

Abstract

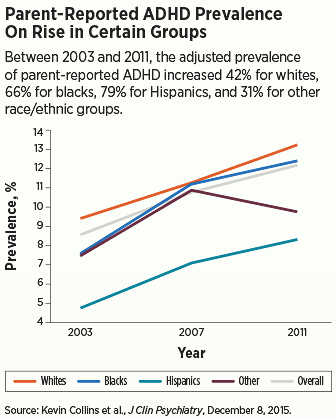

Although ADHD prevalence remains highest among whites, increasing trends were observed for all racial/ethnic groups, most notably among Hispanics.

As the number of U.S. youth diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) continues to rise, a recent study has revealed that the prevalence is climbing faster in some groups of children than in others.

The study, published online December 8, 2015, in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, was based on information collected by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as part of the National Survey of Children’s Health during 2003, 2007, and 2011 (including 190,408 children aged 5 to 17). As part of this survey, parents were asked whether they had ever been told by a doctor or other health care provider that their child has ADHD.

According to the study, the overall weighted prevalence of parent-reported ADHD rose from 8.4 percent in 2003 to 12.0 percent in 2011—a 43 percent increase. Although ADHD continues to be more likely to be diagnosed in boys, parent-reported ADHD prevalence for girls climbed from 4.7 percent in 2003 to 7.3 percent in 2011—a 55.3 percent increase compared with a 39.8 percent increase in boys.

The researchers also examined parent-reported ADHD prevalence across four categories of race and ethnicity: white non-Hispanic, black non-Hispanic, Hispanic, and other non-Hispanic. Although ADHD prevalence remained highest among whites, there was an 83 percent increase in parent-reported ADHD diagnosis for Hispanics, followed by black non-Hispanics at 58 percent.

“I don’t think that the overall increase in the number of ADHD diagnoses in children and adolescents surprised anyone, since we’ve been seeing this increase over the past three decades,” lead author Sean Cleary, Ph.D., an associate professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the Milken Institute School of Public Health at Washington University, told Psychiatric News. “Some of the major surprises observed were the dramatic increase in [parent-reported] ADHD diagnosis in young females and Hispanic youth, which to my knowledge has never been reported before,” he emphasized.

Cleary noted that while the current study was not designed to uncover the factors that may be driving the uptick in ADHD diagnoses in youth, the findings may reflect growing recognition by health care providers that ADHD symptoms can manifest differently in girls than in boys. For example, boys may be more likely to display ADHD symptoms externally, through vocal and loud behaviors, whereas girls may appear more withdrawn, he said.

Cleary’s group also hypothesized that the increases in ADHD prevalence among Hispanics may reflect increasing mental health resources as well as a greater cultural acceptance of the illness.

No funding was reported for the study. ■

An abstract of “Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Parent-Reported Diagnosis of ADHD: National Survey of Children’s Health (2003, 2007, and 2011)” can be accessed here.