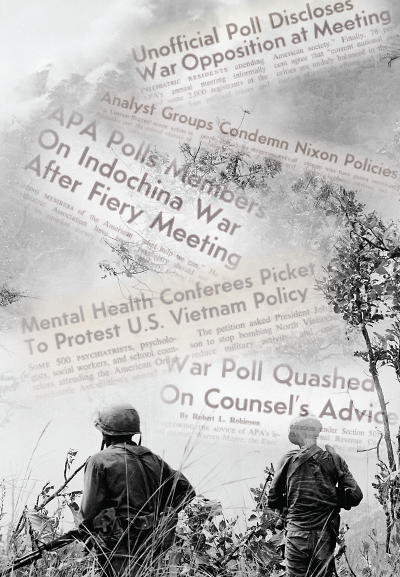

APA Members Speak Out During Vietnam War

Abstract

PTSD came later, but the tumult engendered by America’s war in Vietnam did not bypass American psychiatry or APA. This article is part of a yearlong series marking the 50th anniversary of Psychiatric News.

The expanded American war in Vietnam began in 1965 but first appeared quietly and inauspiciously in the pages of Psychiatric News a year later.

“The number of U.S. servicemen evacuated as noncasualties in recent months from South Vietnam because of psychiatric disorders ranks second only to malaria patients” began the story in the May 1966 issue, picked up from the Medical Tribune. “American military psychiatrists say, however, that most mental disorders they see are not triggered by the war.”

The war that led to the current diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder had recorded just one official case of “combat fatigue” in its first eight months of escalated fighting. At that time, the Army had nine psychiatrists based in Vietnam responsible for 129,000 troops.

“One psychiatrist said he had observed that combat fatigue among ground troops is less a problem in this war than it was in World War II and the Korean conflict for three reasons: a) because of the availability of helicopters to supply or evacuate them, the men face little danger of isolation; b) they are not under the constant bombardment that sometimes occurred in the two earlier wars; and c) they have been told that their assignments to South Vietnam are for only one year.”

Within a year, though, the antiwar movement in the United States was making its voice heard, and mental health clinicians were among those urging the war’s end.

“Some 500 psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and school counselors attending the American Orthopsychiatric Association’s annual meeting in Washington called for an end to the Vietnam war in a demonstration at the White House on March 22,” noted Psychiatric News in its May 1967 issue.

Robert Liberman, M.D., then a resident at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Cambridge, said the group opposed the war both on humanitarian grounds and for drawing off federal funding for health, research, and education.

Later, a group of physicians sought to bring wounded Vietnamese children to the United States for general and plastic surgical treatment and place them temporarily in American homes for care.

“Seventeen psychiatrists are among the 120 sponsors of the Committee of Responsibility to Save War-Burned and War-Injured Vietnamese Children, which plans to sponsor medical aid for badly injured children who cannot receive proper care in Vietnam,” reported Psychiatric News. Signatories included Leo Kanner, M.D., of Johns Hopkins, who first published a description of autism; and Judd Marmor, M.D., APA president for the 1975-76 term.

The intersection of the war with medical ethics concerned other APA members.

“I am ashamed that the invention and use of chemical and biological warfare and warfare in general in Vietnam requires the active participation of the American medical doctor,” wrote Los Angeles psychiatrist and World War II veteran Albert Schrut, M.D., in a letter to the editor in the July 1967 issue. “American medicine, which stands in a cardinal position of respect as a treasurer of human life, has not provided the morality nor the courage to bear that pressure which is within its power to end its government’s wanton disrespect of innocent human lives.”

A poll of 2,000 doctors that included 142 psychiatrists found that 66 percent of psychiatrists and 62 percent of all physicians disapproved of President Lyndon Johnson’s policy in Vietnam, according to the April 1968 issue. However, 51 percent of psychiatrists favored more active U.S. peace efforts, compared with 36 percent of all doctors. The article also reported that psychiatrists had been more likely to vote for John Kennedy in 1960 and Johnson in 1964 than their colleagues in other medical specialties.

In the October 1968 issue, Editor Robert Robinson noted the advent of a “new order of things.” APA set up task forces to look at “psychiatry and foreign affairs, and poverty, and aggression and violence. …”

The first inkling that perhaps all was not well when the troops returned home appeared in the January 1970 issue.

“Vietnam War veterans are not receiving the same level of psychiatric treatment as veterans of World War II or Korea received,” according to Louis Jolyon West, M.D., an APA trustee and a professor and chair of psychiatry at UCLA. West urged the VA to modernize and upgrade treatment, research, and facilities.

“The Vietnam veteran returns home with problems different from those of the World War II veteran, some of which are related to the ‘unpopular status of the war,’ Dr. West believes. Others ‘reflect the generally shifting picture of psychopathology in a rapidly changing culture like our own.’ ”

Protests against the war had been going on for years, but any hopes that they might bring it to an end were dashed by the U.S. incursion into Cambodia, which began just 10 days before the 1970 annual meeting in San Francisco. A few days later, four students were shot and killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State University.

So it was that the 60s—as an era—struck APA head on at its annual meeting, “the most tumultuous annual meeting in APA’s history, punctuated with the introduction of numerous political resolutions, demonstrations by dissident groups, demands for curtailment or cancellation of the annual meeting events, and angry exchanges on the meeting floor and off.”

In response, APA President Raymond Waggoner, M.D., decided to hold an open session on Monday after the traditional presidential address. Karl Menninger, M.D., began by saying, “The greatest hope we have is our young people, and we ought to offer them what help we can.”

Speakers from the floor variously condemned the Cambodian incursion and called for “an end to the undeclared war on Black Panthers” and a cessation of war-related activities on university campuses.

“Members of the Women’s Liberation paraded quietly around the floor, … charging that psychiatrists perpetuate the ‘myth of male superiority’ and discriminate against women,” reported Psychiatric News. “A spokesman for the Gay Liberation also attacked psychiatry for its ‘oppression of homosexuals.’ ’’

During the APA business meeting the next day, members introduced resolutions about Vietnam and Cambodia, “but as words became harsher, tempers flared.”

Someone moved to adjourn the meeting. Waggoner called for a voice vote and declared the meeting adjourned, to the dissatisfaction of many. APA members attending a special business session on Thursday voted to distribute by mail a survey with 11 questions to members. Eight questions concerned the war in Southeast Asia. One addressed “poverty as a major factor in the development of mental illness,” one condemned “disruptive tactics” of demonstrators at the San Francisco meeting, and one urged “APA action on behalf of understanding the problems of youth.”

Letters to the editor that appeared in later issues tended to mix personal opposition to the war with arguments that it was inappropriate for APA to take an organizational stand.

In any event, the “War Poll” fizzled out by fall 1970. APA, on the advice of its legal counsel, decided to neither publish nor implement the results of the survey, on the grounds that it would jeopardize APA’s status as a scientific and educational organization, according to the October 7, 1970, issue. (Psychiatric News transitioned from a once-a-month publication to twice a month in July 1970.)

Some members were skeptical of the process and the outcome.

“We question whether it is proper for APA to take a stand on such a ‘purely political’ issue as the war, but we find APA is not so reluctant to take a stand on several other political issues,” wrote Edmund Kal, M.D., of Oakland, Calif., in the October 21, 1970, issue. “[T]he inconsistency of the human mind never ceases to amaze me. But when this inconsistency appears in the group of people that by its very profession holds itself out to be the arbiters of consistent thinking, one begins to wonder.”

However consistent APA’s positions appeared at the time, the Vietnam war era was probably not the first time and was certainly not the last the organization was asked to take a stand on controversial issues of the day. In the years since, not only war but also race, gender, sexual orientation, and other social and clinical issues have provoked debate and called forth leadership and decisions from APA. ■