Health Care Reform Was in the Air in the 1970s but Little Came of It

Abstract

Modern health care reform didn’t start with the Clintons in the 1990s. Richard Nixon and many other players proposed various plans in the early 1970s that never came to fruition.

While waiting for a Republican-dominated Congress to repeal the Affordable Care Act (ACA) for the umpteenth time, you might find it interesting to stroll back through the pages of Psychiatric News and see what kind of a health care plan a certain long-ago Republican president proposed.

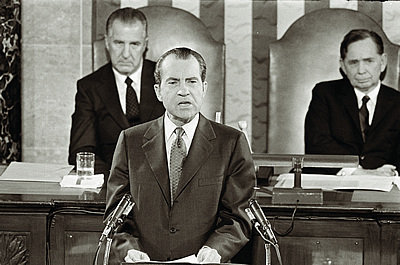

Richard Nixon was nothing if not persistent in trying to get Congress to pass health care bills. In 1971, he urged lawmakers to pass his National Health Insurance Partnership Act. These and other proposals to reform the health care system were sketched out for the benefit of APA members in a series of articles in the pages of Psychiatric News in 1972.

Perhaps if any of these initiatives had been enacted in the early 1970s, the movement toward comprehensive health reform and more inclusive health insurance coverage might not have had to wait for the ACA. However, a review of these varied proposals turns up some of the ancestry of the current law.

The first part of Nixon’s plan would have required employers to provide health insurance for employees and their dependents. Employers would pay the major share of premium costs, and employees would have to cover certain copayments. The plan would be “administered and underwritten by private carriers.”

The second element was the Family Insurance Plan for low-income families not insured under employers’ plans. This would cover 30 days of hospital care, doctor visits, emergency services, well-child care, and lab services. The Family Plan would be administered like Medicare—by the federal government using behind-the-scenes intermediaries.

In these Nixon plans, “psychiatric coverage is not clearly defined,” reported Psychiatric News, working from material collated by drug manufacturer Smith Kline & French. “[T]he bill excludes services of a psychiatrist for inpatient and outpatient care.”

Anonymous congressional or White House “staffers” apparently hinted that various forms of psychiatric hospitalization would eventually be included in the plan, a reminder that institutional care for patients with mental illness was still a prominent part of the treatment landscape.

The bill would also promote the establishment of health maintenance organizations “to provide comprehensive services to [a] voluntarily enrolled population for a fixed fee [and] would encourage group practice and restructure [the] delivery system.”

At the same time, Democratic Sen. Edward Kennedy of Massachusetts joined with Republicans Sens. William Saxbe of Ohio and John Sherman Cooper of Kentucky in proposing the Health Security Act of 1971. The legislation would cover “the entire range of personal health care services: no cutoff dates, coinsurance, deductibles, or waiting periods.”

The bias favoring institutional care remained, but there were also openings for other avenues of psychiatric treatment. Limitations on inpatient psychiatric stays were mandated but also allowed outpatient psychiatric care “furnished by a hospital or comprehensive health or mental health facility … or 20 consultations during a benefit period if furnished otherwise than at the facilities mentioned above.”

The AMA, long an opponent of national health insurance and “socialized medicine,” offered its own plan, based mainly on “tax credits provided against individual income taxes to offset the cost of private health insurance purchased by the taxpayer.” Psychiatric coverage was again described in terms of hospital care, although “physicians’ services,” presumably including those provided by psychiatrists, were covered too.

The American Hospital Association weighed in with its proposal, one that foreshadowed the current wave of institutional consolidation.

The program would be “[a]dministered by health care corporations, which everyone would be encouraged to join. Corporations would bring together health care management personnel and facilities of a given geographical area into a corporate structure.” Such corporations would be paid with “federal and private funds, with coverage based on ability to pay,” said the AHA.

Psychiatric coverage would include “immediate care for persons suffering from alcoholism, drug abuse, and acute mental illness.” Furthermore, various forms of long-term psychiatric care then carried out in local, state, and federal facilities would be folded into the larger corporate system.

The ACA’s incorporation of a central role for private health insurance companies is another old/new idea. The Health Insurance Association of America’s plan included something very like the exchanges that are a key to the ACA: “State pools of private health insurers supported by public funds would insure those unable to pay for or secure health insurance.”

Psychiatric coverage was complicated, but usually covered only half of psychiatrists’ or hospitals’ fees.

Republican Sen. Jacob Javits of New York suggested a compulsory health insurance system designed to eventually replace Medicare and Medicaid. Private insurance would be permitted but only if the benefits were superior to those in the public system. Psychiatric coverage was again focused on inpatient care, with limited lengths of stay.

Nixon did not give up. A health maintenance organization act was passed late in 1973, a step designed to “encourage more freedom of choice for both patients and providers, while fostering diversity in our medical care delivery system.”

Early in 1974, Nixon again sent a message to Congress urging passage of his Comprehensive Health Insurance Plan. It called for a mix of employment-based insurance, Medicare, and “Assisted Health Insurance” for poor, unemployed, disabled, and self-employed people. Psychiatric care was included. It would be paid for by existing state and federal revenue, he said.

Nixon’s proposals could be viewed as even more far reaching than the ACA, but their demise was tinged with irony, said Gary Freed, M.D., M.P.H., and Anup Das, B.A., of the University of Michigan, writing in the August 2015 issue of Pediatrics.

“The Nixon plan,” stated Freed and Das, “was defeated by Democratic forces in Congress at that time, led by Sen. Edward Kennedy, who advocated for the development of a single payer system.” ■