Living Longer, Living Well

Abstract

Two million Americans are now age 90 or older, and this group includes more than 1,000 APA members. Profiled here are three psychiatrists in their 90s whose active professional lives, community service, and leisure pursuits serve as role models for the rest of us.

Seeing With the Mind’s Eye: A Profile of Barbara Young, M.D.

Barbara Young, M.D., a Baltimore psychiatrist, psychoanalyst, photographer, and film critic, marked her 95th birthday last October 27 with the publication of her third book, The Persona of Ingmar Bergman: Conquering Demons Through Film.

An invitation to discuss Bergman’s film “Wild Strawberries” at the Baltimore-Washington Psychoanalytic Film Forum in 2010 sparked her interest in exploring the Swedish filmmaker’s life, Young told Psychiatric News.

She recalled seeing one of Bergman’s films, “The Seventh Seal,” in the late 1950s, just as she was starting what would become her second profession, photography. To write her book, she watched over 40 Bergman films and interviews.

“We all have demons that have accompanied us since childhood,” Young asserted. Bergman’s characters struggle, as Bergman did, she said, to work through fears of death, punishment by God or parents for sins, loneliness, intimacy, loss of control of murderous rage, and other existential dilemmas.

Bergman successfully analyzed himself, a rare achievement, Young said. His self-analysis started with his first films and continued throughout his life. Once learned, she said, analysis is a never-ending process.

Young grew up in rural Brimfield and Galesburg, Ill. Her father was a minister, and her mother, a former teacher of Latin, Greek, and German. Young graduated from Knox College, Galesburg, in June 1942 and entered medical school that month at Johns Hopkins University, one of eight women in her class. Because of the wartime need for physicians, students attended classes year-round for three years.

After a year as an intern and another in neurology at the University of Iowa Hospital, Young returned to Hopkins for her psychiatry residency. John Whitehorn, M.D., a professor and chair of psychiatry, urged residents to focus on patients’ strengths, she recalled, not their diagnosis. Whitehorn served as APA’s president for the 1950-51 term.

After completing her residency, Young worked for two years as a staff psychiatrist at the Perry Point Veterans Hospital. She opened her still-ongoing private practice in Baltimore in 1951 and graduated from the Baltimore Psychoanalytic Institute in 1953. She never married.

Being a photographer, Young said, has both enriched her life and made her a more attentive and thoughtful therapist. In 1958, her brother Arthur gave her a Brownie camera to take on vacation in the Bahamas. “Barbara, you’ve got the eye,” he told her after seeing her photos. “But you need a better camera!”

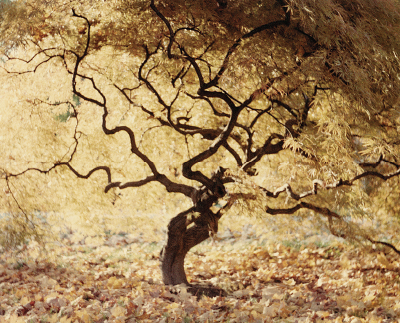

In the early 1960s, museums were just starting to include color photography in their collections. Edward Steichen, then curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, purchased one of Young’s first color works, “Golden Leaves.” The image of a gnarled Japanese maple in the fall, crowned by early morning sunlight, Steichen wrote Young in 1962, “gives the feeling of what might be behind a troubled mind as expressed in the twisted turbulences one finds in nature.” He paid her $10 for this work.

“When I take a photograph, I see the design,” Young said. “When I look at the enlargements, I am whisked back to the place where I was standing when I took the photograph. Only later do I realize that some of the images speak of significant psychological things.”

When Young developed arthritis in her hip in the early 2000s, her physical therapist advised her to swim. After getting to know fellow swimmers at Baltimore’s League for People With Disabilities, she brought her camera to the pool. Her interviews and photos made up a 2003 book, Tales of Courage: Recovering Life after Catastrophe.

In the early 2000s, Young contacted her former patients to ask how they remembered their therapy and had incorporated it into their lives. In 55 years of practice, she said, she had worked with 22 patients in classical three- or four-day-a-week psychoanalysis and saw 231 patients overall, most in psychotherapy lasting a year or longer. The number may seem small, she said, but treatment often benefited not only her patients but also their partners, children, pupils, and, sometimes, their own patients.

“The most important element in the forward movement of any treatment is the strength of the working connection between patient and therapist,” she noted in her summer 2007 report, “The Efficacy of Psychoanalysis and the Analytic Therapies: Reflections of a Psychoanalyst and Her Former Patients,” in the Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis and Dynamic Psychiatry.

Young still sees patients—“My last three patients,” she asserted—in an office on the second floor of her home. She has taken photographs from the office window for decades, documenting seasonal changes in the park across the street. Her analytic couch sits beneath that window. Young’s chair at the head of the couch lacks an outdoor view, however. While seeing patients, she focuses on their inner landscapes.

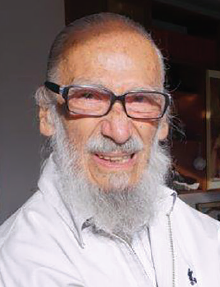

Going for the Gold: A Profile of Hugo Delgado, M.D.

For 91-year-old Peruvian psychiatrist Hugo Delgado, M.D., life in the fast lane is no metaphor.

In the past 27 years, Delgado has won more than 20 gold and silver medals in international track and field competitions, including the 100- and 200-meter dash and 80- and 300-meter hurdles. He came in first in his age category in the World Master’s Championship 100-meter race in Lyon, France, last August, covering the distance in 19.73 seconds. The Olympic record for this event, 9.63 seconds, was set in 2012 by Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt, then 23 years old.

Delgado started running competitively only at age 65, when he entered an athletic tournament for seniors. He recently spoke with Psychiatric News at his home in Arequipa, Peru, discussing his athletic feats, psychiatric career, and participation in civic affairs. Renato Alarcón, M.D., emeritus professor of psychiatry and psychology at the Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, also a native of Arequipa, conducted the six-hour interview in Spanish and translated his notes for this report.

To prepare for his first international race in 1989, Delgado gave up the pack-a-day smoking habit he had acquired in adolescence and stopped even his modest social drinking. With help from a coach friend, he adopted a training regimen he maintains today. It includes daily runs and gymnastics, regular sleep, and a healthy diet. He hopes to enter an international hurdles competition this year or next.

Delgado, born in Arequipa in 1924, was the youngest of six children. He graduated from what was then Peru’s only medical school, the Universidad Nacional de San Marcos (National University of San Marcos) in Lima in 1954. His uncle, Honorio Delgado, M.D. (1892-1969), the medical school’s chair of psychiatry for nearly 30 years and a luminary of Latin American psychiatry, encouraged his interest in the field.

It was immersion in patient care, however, Delgado said—“the opportunity to establish deep and empathetic contact with psychiatric patients through spontaneous dialogues and formal interviews”—that solidified his choice of specialty. Working at what was then Peru’s only psychiatric hospital, he gained experience managing both acute and chronic psychiatric disorders.

After 12 years in Lima, Delgado returned to Arequipa, serving first as a staff psychiatrist, and, later, chief of psychiatry, at Arequipa’s Universidad Nacional de San Agustin (National University of San Agustin) medical school, which opened in 1958.

After earthquakes in 1958 and 1960 severely damaged Arequipa’s only city hospital, Delgado helped transform a hospital for tuberculosis patients into a general hospital. He became a staff psychiatrist there and persuaded authorities to name the psychiatric service, and, later, the hospital itself, for his uncle.

He helped establish the city’s first community mental health center in the1970s and organized several national psychiatric meetings in the city.

Seeing severely disturbed patients, particularly those who were psychotic or depressed, respond to pharmacological interventions or electroconvulsive therapy, he said, ranks high among his professional satisfactions. “To share the hope of continuous progress with patients’ relatives and to witness it during follow-up visits,” he said, “contributed to the sense that I was doing something useful.”

In his private practice as a psychotherapist, Delgado said, “I didn’t follow a particular technique or school, but found that emphasizing memories of positive experiences in different periods of the patient’s life almost always had a favorable effect.”

In his own life, he uses a strategy he often urged on his patients—“and anyone else who would listen,” he said—“ ‘to remain hungry,’ that is, not to go to bed at night feeling fully satisfied in any aspect of life, but rather to acknowledge that there always is something else waiting to be done.”

On a typical day, in addition to his daily athletic training, Delgado reads for a couple of hours, enjoying weekly magazines and literature, such as Cesar Vallejo’s poems and Ricardo Palma’s classic Peruvian Traditions. He helps with domestic duties, such as housecleaning, and he likes to cook. Delgado and his wife, Antonieta, who have been married 64 years, have two daughters, six grandchildren, and one great-grandchild.

A local celebrity, Delgado served several terms as a member of Arequipa’s City Council and later as Arequipa’s deputy city mayor.

“I never thought that I would get to the point of being warmly greeted in the street by somebody I didn’t know, somebody who wants to have a picture taken with me,” he noted. “That makes me feel somewhat overwhelmed and humble. On the other hand, I feel mostly relaxed. I know I’ll die some day, but I don’t lose any sleep over that.”

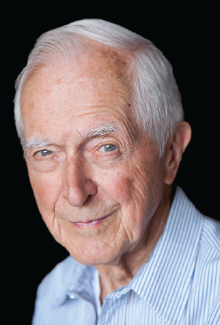

A Life of Service: A Profile of Robert McAllister, M.D.

Growing up on a Montana wheat and cattle ranch in the 1920s, Robert McAllister, M.D., Ph.D., developed an appreciation for nature’s beauty and a spiritual compass that guides his life today.

McAllister, who is 96, has been a practicing psychiatrist, psychiatric hospital superintendent, academic, and consultant. He just sent his sixth book to the printer, a memoir, 95 and Counting: My Cup of Life.

McAllister spent nine years as sole caregiver for his wife of 50 years, Jane, who died of Alzheimer’s disease in 2012. Soon after Jane’s diagnosis, he helped her craft her memoir, Before It’s Too Late: Alzheimer’s: Return of Childhood Emotions, published in 2009.

McAllister also wrote An Alzheimer’s Love Story, published in 2012, and frequently speaks on the caregiver role. He lives at Vantage House, a retirement community in Columbia, Md., and writes essays for its newspaper. He also contributes to Psychiatric News.

“I loved being a psychiatrist, particularly doing psychotherapy,” McAllister told Psychiatric News. “I felt I lived the life of the person I was talking to. I learned something new about psychiatry and about life from every patient I ever saw.”

McAllister took a circuitous path to his psychiatric career.

The youngest of eight children, he joined field crews on the ranch by age 10, driving a team of horses that pulled a hay rake. “At an early age I was being productive; I was contributing,” McAllister said. The need to be of service proved a lifelong source of motivation.

Planning to enter the priesthood, McAllister attended Loras College in Dubuque, Iowa, and then St. Edward’s Seminary in Seattle. After two years there, he decided not to become a priest. He enlisted in the Army in 1943, becoming an infantryman who fought in Patton’s Third Army. While in Austria, he saw firsthand the horrors of extermination camps.

After the war ended, he married a Swiss woman. The couple lived at the Montana ranch for a year and then moved to Washington, D.C., where McAllister attended Catholic University with the aid of the GI Bill, earning his Ph.D. in psychology in 1952. One of his professors, psychiatrist Robert Odenwald, M.D., encouraged him to go to medical school. McAllister planned from the outset to become a psychiatrist.

He received his M.D. from Georgetown University School of Medicine in 1956, earning money for his tuition using his carpentry and other skills he had acquired in the fix-it-yourself life on the ranch. He completed his psychiatric residency at Seton Psychiatric Institute in Baltimore in 1960.

McAllister was 41 by the time he began practicing psychiatry. He taught at Catholic University for several years. In 1966, he and his wife divorced, and he moved to Reno, Nev., to become superintendent of the Nevada State Hospital. He and Jane married later that year.

In 1965, McAllister and James Vanderveldt, O.F.M., published their report, “Psychiatric Illness in Hospitalized Catholic Religious,” in the American Journal of Psychiatry. McAllister wrote Conflict in Community, published in 1969; Living the Vows, Emotional Conflicts of Celibate Religious, published in 1986; and Emotions: Mystery or Madness, published in 2007.

His publications and extensive experience as a therapist for Catholic priests and nuns dealing with depression and other mental illnesses that sometimes were related to their choice of a religious life brought him frequent invitations to lecture, conduct workshops, and consult on mental health and religion.

In the 1970s and early 1980s, McAllister practiced in Grants Pass, Ore., and taught at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Wash. In 1985, he moved to Baltimore, where he taught in Loyola University’s Pastoral Counseling Program for 22 years.

In the same years, he also directed the Isaac Taylor Institute of Psychiatry and Religion, an inpatient program for religious professionals of all faiths, at Taylor Manor Psychiatric Hospital in Ellicott City, Md. After the hospital was sold in 2002, McAllister opened a private practice in Ellicott City, which he continued until December 2005. He currently provides supervision for a licensed clinical social worker, he said, “a highlight of my week.”

“I entered psychiatry when talk therapy was the therapy,” McAllister recalled. Despite recent advances in psychiatric medications, people need talk therapy, he asserted, to recover from emotional damage triggered by past or current life events.

Psychiatrists, and others in the helping professions, McAllister said, need to be able to share work-related anxieties and concerns with a trusted confidant. His wife, Jane, had filled that sounding-board role for him, he said. “She didn’t know my patients. She may or may not have responded to what I said, but she heard me. That was all I needed.” ■

A fourth profile in this series—that of Martin Kassell, M.D., of Scottsdale, Ariz.—will appear in the next issue.