Concussion May Influence Long-Term Risk of Suicide

Abstract

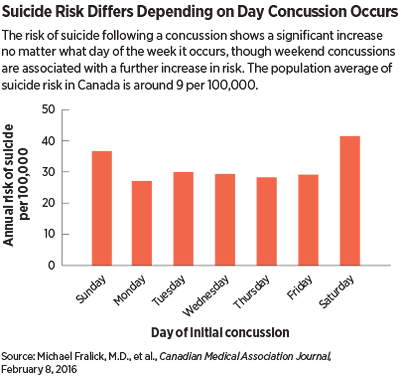

The risk of suicide among those with a concussion was three times the population norm and was even higher if the concussion occurred on a weekend.

Concussions are defined as a transient disruption in mental function brought on by trauma. However, the effects of a concussion are frequently much more persistent—ranging from recurring headaches and dizziness to depression and posttraumatic stress disorder. While some studies suggest that severe head injuries increase risk of suicide, it is unknown whether concussions, which are classified as a mild traumatic brain injury, also increase suicide risk.

To determine whether concussions increase the long-term risk of suicide, a research team at the University of Toronto conducted a retrospective analysis of over 235,000 patients who had been diagnosed with a concussion that did not require hospitalization from 1992 to 2012. The researchers explored the overall rate of suicide in this group, as well as whether weekend versus weekday concussions affected suicide risk.

The results, which were published in the Canadian Medical Association Journal, showed that concussions were associated with about a threefold increased risk of suicide (31 deaths per 100,000 people annually). Those with a concussion occurring on weekends accounted for an absolute suicide risk of 39 per 100,000 or four times the population norm (a one-third increase in suicide risk after a weekend concussion relative to a weekday concussion).

As lead author Donald Redelmeier, M.D., of Toronto’s Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre told Psychiatric News, numerous factors likely influence why concussions that take place on weekends are of greater risk than those that take place on weekdays. One key distinction, he said, is that weekend concussions typically arise from recreational activities, while concussions that occur on weekdays are more likely to be caused by occupational injuries.

Employer rules and safeguards, for example, might ensure that an injured employee gets immediate medical evaluations and takes some time off of work, which helps the brain heal.

“But often if someone gets a concussion due to a weekend misadventure with friends, they’re often back doing the same activity the next day,” he said.

Several other baseline factors, such as low socioeconomic status, prior psychiatric diagnosis, and past suicide attempts also predicted the long-term risk of suicide. However, even patients with no prior suicide attempt, psychiatric diagnosis, or hospital admission had about twice the long-term suicide risk of suicide as the general population.

Craig Bryan, Psy.D., an assistant professor of clinical psychology at the University of Utah who was not involved with the study, said that these findings correlate strongly with work that he has done assessing veterans who have experienced traumatic brain injury.

“We are seeing some consistent associations between brain injury and subsequent risk of suicide ideation or action across demographics,” he told Psychiatric News. “The big question now is why. For example, is the impact to the frontal lobe that results in impaired decision-making processes a key driver? Or are other types of damage more influential in shaping behavioral outcomes?”

Bryan said he believes that more research that considers the associations between how, when, and where a concussion is sustained and suicide risk will be needed to tease out the neuropathology of the trauma.

In the meantime, Redelmeier said that he hopes the results of their study raise awareness among health professionals about the role of concussions in mental health. “Prevention should be a priority, so if someone sees a patient with a previous concussion or who might be at risk—which should be elicited when discussing a patient’s history—then it’s important to reinforce the importance of safety over recklessness,” he said. “Greater attention to the long-term implications of a concussion in community settings might save lives.”

This study was supported by a Canada Research Chair in Medical Decision Sciences, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Major Frederick Banting Chair in Military Trauma Research, the Canadian Forces Surgeon General’s Health Research Program, and the BrightFocus Foundation. ■

An abstract of “Risk of Suicide After a Concussion” can be accessed here.