Hinckley Freed, But Judge Sets Numerous Restrictions

Abstract

The implications of the “not guilty by reason of insanity” defense surface again as John Hinckley leaves St. Elizabeths Hospital after 34 years.

John Hinckley Jr., who wounded President Ronald Reagan and three other people on March 30, 1981, was scheduled to be released after August 5 to his mother’s home outside Williamsburg, Virginia, on “convalescent leave” from confinement in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C.

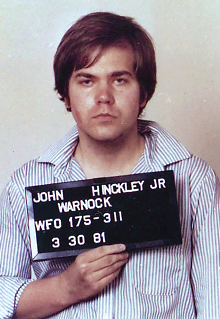

This mugshot of John Hinckley Jr. was taken shortly after he attempted to assassinate President Ronald Reagan in 1981.

“[T]he Court finds by a preponderance of the evidence that Mr. Hinckley will not be a danger to himself or others if released … under the conditions proposed by the Hospital, as modified and supplemented by the Court in this opinion,” wrote Judge Paul Friedman of the United States District Court for the District of Columbia in his July 27 opinion.

Hinckley must avoid contact with his victims and their families, the media, the U.S. president, and members of Congress and may not use social media or alcohol or possess a weapon, among other restrictions the judge ordered.

In addition, he must remain in therapy in Williamsburg and return to St. Elizabeths monthly for outpatient treatment, said Friedman.

Hinckley, now 61, remained in St. Elizabeths for 34 years, except for 80 unsupervised visits with his family.

“Since 1983, when he last attempted suicide, he has displayed no symptoms of active mental illness, exhibited no violent behavior, shown no interest in weapons, and demonstrated no suicidal ideation,” said the judge. “The government and Hospital both agree that Mr. Hinckley’s primary diagnoses of psychotic disorder not otherwise specified and major depression have been in full and sustained remission for well over twenty years.”

“I think the conditions of release seem reasonable for someone said to have been symptom-free for many years,” said Paul Appelbaum, M.D., the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and director of the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. The judge left many decisions about changes in the requirements up to Hinckley’s clinicians, rather than requiring a court hearing before every change, noted Appelbaum.

That makes sense given that Friedman’s order primarily relates to Hinckley’s treatment regimen and to his activities, such as displaying his artwork or participating in social media on the internet, Appelbaum said. “The concerns related to both of those are that they may fuel his psychopathology—specifically his desire for notoriety—so whether that occurs is best determined by his treatment team as well.”

Hinckley’s release under the conditions imposed by Judge Friedman also seems appropriate to William Carpenter, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and pharmacology at the University of Maryland School of Medicine in Baltimore and the Maryland Psychiatric Research Center. Carpenter evaluated Hinckley before his trial, documenting a 10-year history of chronic severe mental illness before the assassination attempt.

“He apparently hasn’t done impulsive or dangerous things for decades,” said Carpenter in an interview. “The clinical people around him have argued that such a conditional release could have been put into place 15 or 20 years ago.”

However, Hinckley’s case is exceptional, since there are few crimes comparable to shooting a president, said Appelbaum.

“One other problem is that we don’t have a good system to understand what happens with insanity acquitees,” said New York forensic psychiatrist Steven Kenny Hoge, M.D., chair of APA’s Council on Psychiatry and Law. “In the 1970s and 1980s, there was some research that indicated that they were likely to be confined longer than if they were convicted, but there has been no similar research over the last 30 years.”

In addition, the release process—possibly reflecting public and political skepticism about the insanity defense—has become more cumbersome, said Hoge. The individual clinician plays a smaller role while that of hospital committees, medical directors, and review boards have grown, both for release decisions and for expanding a prisoner’s privileges within the hospital.

The lengthy and stringent set of restrictions on Hinckley’s activities is typical, although Friedman went into more detail than with most orders, said Hoge.

The psychiatrist, social worker, and therapist overseeing Hinckley’s progress in Williamsburg must supervise his activities and encourage his further integration into society by expanding volunteering or employment to avoid the downward internal spiral that led him to attack Reagan.

“Before the assassination attempt, he became dangerous after years of virtual isolation, so the key to his success now is social engagement and careful follow-up by his treatment team in Williamsburg,” Carpenter said.

Ironically, perhaps Hinckley would have been better off had he not used the insanity defense, suggested Carpenter. He would have been less socially isolated at the federal prison in Butner, North Carolina, than in the high-security ward at St. Elizabeths, and release from having completed his sentence may have come earlier.

“Although an insanity verdict is often seen as equivalent to a finding of not guilty, in fact, as this case demonstrates, it has a punitive aspect as well,” said Appelbaum. “That’s why, I believe, the length of confinement is usually proportionate to the severity of the crime, and why it has taken so long for a man reported to have been without symptoms for over 20 years to be conditionally released.”

That may not be a bad thing, added Appelbaum. “Public acceptance of the possibility of an insanity defense may depend on the perception that it’s not equivalent to a ‘get out of jail free’ card—which it most certainly is not.” ■