Experts Warn Against At-Home Electrical Stimulation Therapy

Abstract

Experts hope to raise awareness and instill caution about the underappreciated practice of do-it-yourself noninvasive stimulation to improve mood or enhance functioning.

Noninvasive brain stimulation is a promising therapy for a wide range of psychiatric and neurological issues, but it’s attracted the attention of a group that has some researchers worried: people who are willing to self-administer brain stimulation to boost brain function.

“As clinicians and scientists who study noninvasive brain stimulation, we share a common interest with DIY [do-it-yourself] users … to improve brain function,” wrote Michael Fox, M.D., Ph.D., associate director of the Berenson-Allen Center for Noninvasive Brain Stimulation at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston and colleagues in a recent open letter in the Annals of Neurology. “However … there is much about noninvasive brain stimulation in general, and tDCS [transcranial direct current stimulation] in particular, that remains unknown.”

Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) involves passing a constant, low-intensity current between two electrodes on the scalp. Several clinical studies have suggested that use of tDCS leads to functional improvements in patients with neurological problems.

“Whereas some risks, such as burns to the skin and complications resulting from electrical equipment failures are well recognized, other problematic issues may not be immediately apparent,” the letter continued.

Fox, who is also an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School and studies the effectiveness of noninvasive brain stimulation, told Psychiatric News that his motivation in penning the letter stemmed from his belief that it was important to raise awareness of the potential risks associated with DIY stimulation.

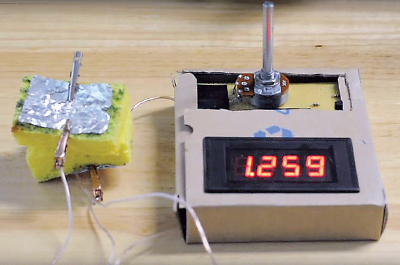

The letter detailed a range of issues and uncertainties surrounding noninvasive stimulation, with an emphasis on tDCS, which is one of the more well-studied noninvasive techniques, and also one that can be readily built or readily bought.

Whether commercially bought or homemade, do-it-yourself electrical stimulation is gaining popularity. Given the risks and uncertainties, however, neuromodulation experts urged caution in a recent open letter.

“You do not need complicated equipment to make tDCS devices, so it lends itself to low-cost and high-market penetration,” said Mark George, M.D., the Layton McCurdy Endowed Chair of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at the Medical University of South Carolina and one of the 39 experts who signed their support of the open letter.

“But we know that anything that has the power to heal or shape the brain also has the power to harm it, so this is an area of great concern for psychiatrists,” he added.

“I get questions about these [consumer stimulation devices] all day long, and if anyone seems curious I say no,” he said. “I know my advice may only go so far for a patient who may be desperate, but I tell them to wait until the evidence for noninvasive stimulation is there.”

One of the major issues with DIY applications, George said, is the variability of the electrical stimulation across individuals; this not only applies to the fact every person will respond to tDCS to a different degree, but also that the intensity needed to produce an effect varies in each person.

“It’s not a one-size-fits-all strategy; a critical first step to treating someone with any type of stimulation, like electricity or magnetism, is to establish his or her threshold,” he said. According to George, determining this threshold is the equivalent of reaching the proper dose of medication.

For established techniques, like transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) or electroconvulsive therapy, clinicians understand how to reach these levels; in TMS, for example, the magnetic energy needed for clinical effectiveness is believed to be the amount required to make a person involuntarily move a thumb.

“But for noninvasive electrical applications like tDCS, we haven’t been able to individually dose yet,” he said. As a result, people using homemade or purchased devices are more often than not applying too much or too little current.

Even if DIY tDCS users achieve some kind of response, there could be subtle consequences of which they aren’t aware, said Fox. “Brain networks are interconnected, so improving the activity of one region may lead to a negative outcome somewhere else,” he explained. In the letter, he used an example that tDCS might help someone learn new material at the expense of losing previously learned knowledge.

“How common are these trade-offs? We don’t know.”

Unfortunately, despite these risks, not much can be done about DIY devices, George told Psychiatric News, as commercial stimulators are not regulated by the Food and Drug Administration. “The companies that make them have also been careful not to use medical terms when they describe their devices,” he said. “Rather, they say they can help you get energized or relaxed.”

Such marketing by the makers of commercial stimulators likely attracts people who do not have a mental disorder, George said, noting that these devices have become popular among video gamers, athletes, and college kids.

What is recommended as a therapeutic option for patients with mental illness may be different from what would be recommended for people without a mental illness, Fox said.

“The goal of tDCS research is to treat brain disease, and if there is a reasonable chance to improve a patient, we can also accept some risks of adverse changes. But we would not accept those risks if we were just trying to enhance function in a healthy brain.” ■

“An Open Letter Concerning Do-It-Yourself Users of Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation” can be accessed here.