When Should Psychiatrists Manage [Other] Medical Conditions?

Abstract

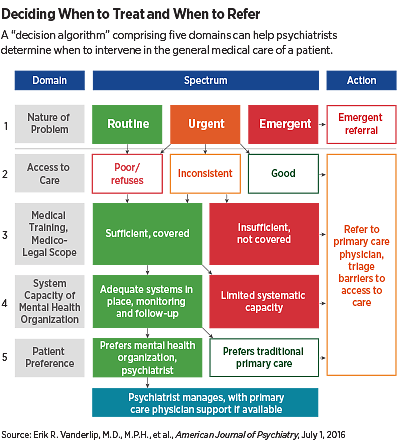

The decision algorithm developed by leaders in integrated care can give psychiatrists some guidance on when it is appropriate to treat patients with common conditions.

Psychiatrists may increasingly be counted on to provide basic primary care—screening for and treating common conditions—to those with serious mental illness and/or substance use disorders.

But when and under what circumstances is that appropriate or necessary?

A “decision algorithm” comprising five domains—the nature and severity of the problem, the patient’s access to existing primary care services, the general medical training and comfort of the psychiatrist, the capacity of the provider’s environment for management and follow-up, and patient preference—can help psychiatrists determine when their primary care skills are necessary and appropriate.

The decision algorithm was developed by Erik Vanderlip, M.D., M.P.H., the George Kaiser Family Foundation Chair in Psychiatry and an assistant professor in the departments of Psychiatry and Medical Informatics at the University of Oklahoma and a member of APA’s Council on Psychosomatic Medicine; Lori Raney, M.D., principal of Health Management Associates in Denver, Colorado, and chair of the APA Work Group on Integrated Care; and Benjamin Druss, M.D., M.P.H., a professor and the Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health at the Rollins School of Public Health at Emory University. The algorithm is described in the July American Journal of Psychiatry.

In interviews with Psychiatric News, all three authors—leaders in the movement to integrate mental health and general medical care—said the algorithm provides a framework by which a psychiatrist considering physical health management could do so in a reasoned, practical, efficacious, and person-centered manner.

“There is no one one-size-fits-all approach for when a psychiatrist should do this,” said Druss. “It depends on how urgent the need is, whether there is somewhere more appropriate that the patient should be getting primary care, the psychiatrist’s familiarity and comfort level, the support the clinician has on site, and the patient’s preference,” Druss said. “Put those together, and this algorithm begins to provide a way to think about these problems.”

Druss said psychiatrists working in the public sector have increasingly been seeking to diminish the mortality gap between the general population and those with serious mental illness (SMI) by providing better care of common medical conditions—especially cardiovascular and metabolic illnesses. In recent years, APA has offered training in primary skills at the Annual Meeting and IPS: The Mental Health Services Conference. Also, last year the APA Board of Trustees approved a position statement declaring that screening and sometimes treating common medical conditions is an essential component of psychiatric practice (Psychiatric News, September 15, 2015).

“We know there is a need, and a lot of psychiatrists are getting the training, and now we have a statement from our professional organization saying that doing this is within the standard of care,” Raney said. “Now the question is, when is this appropriate? We decided that if we had something published, it might help clinicians be less anxious about practicing outside of our traditional scope. The graph can help a psychiatrist walk through when he or she can and should be providing primary care and when the patient should be referred.”

Vanderlip said the psychiatrist is sometimes the only person who knows what kinds of conditions are impacting the patient’s health. “But that psychiatrist may often be unclear about where to draw the line and actually intervene,” he said. “What we tried to do is establish a framework that a general psychiatrist could use to decide whether or not they should manage general medical conditions.”

Each of the five domains is broken down into two or three descriptors, which then lead variously to a decision to treat, refer to primary care, or refer to emergency care. For instance, the domain of “system capacity for management and follow-up” is broken down into two possibilities—adequate systems in place or limited system capacity—which (depending on other domains) leads to a decision to treat or refer (see chart). System capacity refers to the availability of staff to take vital signs or blood draws, for instance, and other factors in the clinician’s practice environment that can support provision of primary care.

The presence of routine or possibly urgent conditions in a patient with poor or no access to primary care coupled with sufficient clinician training, legal coverage, system support, and the patient’s approval for receiving care in a mental health setting leads to the decision that the psychiatrist can manage the patient.

Raney added, “The take-away message is that we are having trouble moving the dial on the mortality gap in the SMI population. There are so many patients who simply won’t engage with primary care. What this decision algorithm does is give psychiatrists some guidance on when it is appropriate to treat common conditions.” ■

“A Framework for Extending Psychiatrists’ Roles in Treating General Health Conditions” can be accessed here.