Final Phase of NIH’s Clinical Trial Reform Kicks Into Gear

Abstract

New changes deal with how funding announcements are handled, but it’s a previous reform that expanded the scope of how the agency defines clinical trials that has some behavioral researchers concerned.

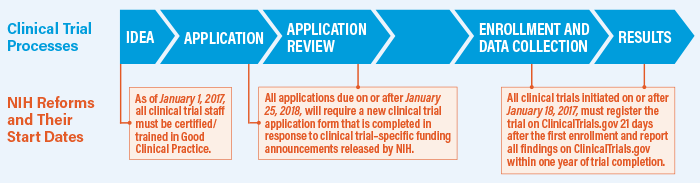

January 25, 2018, will be an important date for researchers who are seeking National Institutes of Health (NIH) funding for clinical trials. Funding announcements with deadlines on or after this date will require applicants to submit new forms specifically designed for clinical trials. NIH will now also have more specific requirements in their grant announcements.

These administrative changes are the final piece of a multiyear effort by NIH to streamline the clinical trial process and increase its transparency—an overhaul that the institute says is needed to ensure the proper stewardship of more than $3 billion in public funds that support clinical trials each year. Other administrative changes introduced in January of 2017 include required training in clinical trial management for all staff involved in clinical trials and new regulations on registering trials and reporting data.

“No one would argue that the principles and intent behind these changes are noble,” said Philip Wang, M.D., Dr. P.H., APA’s director of research. “However, when implementing any important change, the devil is always in the details.”

What Defines a Clinical Trial?

One of the details that has generated a stir among researchers is how NIH classifies a clinical trial: A research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes. This definition was established in 2014.

Many scientists believe NIH’s definition is too broad and reclassifies studies long viewed as addressing basic scientific questions as clinical. Under NIH’s definition, a scientist evaluating whether low-dose neurostimulation improves memory in healthy volunteers would be conducting a clinical trial. If the scientist limited the study to examining the effects of neurostimulation on brain activity, this would not be considered a clinical trial.

Some scientists are confused by this definition, and worry that they will submit their grant to the wrong place and possibly miss out on funding because they thought their work was not under the clinical-trial umbrella. Other researchers have voiced concerns that behavioral studies might experience a reduction in funding since they will now have to compete with more medically oriented research. Individuals and societies involved in psychology and neuroscience research have been especially vocal in their criticism of this definition, given that these fields conduct lots of exploratory studies with human subjects.

Michael Lauer, M.D., says that NIH believes that any human studies involving interventions or manipulations require a higher degree of accountability.

Michael Lauer, M.D., who has overseen this process as the NIH deputy director for extramural research, told Psychiatric News that he appreciates the concerns raised by many stakeholders over this broad and nuanced definition. However, he and others at NIH believe that the expansion of clinical trial criteria was needed to recognize all the people who agree to participate in experimental studies.

Categorizing every study with humans as a clinical trial (as some people advocated for when NIH first released its proposed changes for public feedback in 2015) would have been too cumbersome, Lauer said. So, the NIH panel instead focused on all intervention-based studies.

“We felt that if a person knows that they may be receiving some intervention that could modify their behavior, then that could have a health impact, and such studies need a higher level of accountability,” Lauer said.

Reforms Promote Transparency, Greater Accountability

Lauer said that NIH’s clinical trial reform efforts began following a critical analysis published in BMJ in 2012 that indicated fewer than half of NIH-funded trials are published in peer-reviewed journals within 2.5 years after completion. The study also showed that data from about one-third of these trials never get published at all.

“I didn’t believe those findings,” said Lauer, who at the time was the head of cardiovascular sciences at NIH’s National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). “We did our own study [on NHLBI-funded trials] and found it was indeed true, especially for trials that did not use hard clinical endpoints [such as disease relapse or death].”

“This became an issue we had to tackle,” Lauer continued. “It’s a waste of money and violation of the trust of the people who agree to participate in clinical trials that so many of them go unreported.”

So, NIH developed an official, comprehensive definition of what a clinical trial entails (which had been previously lacking) as well as a series of rule changes designed to ensure better accountability by clinical trial investigators. The first phase went into effect in January 2017 and mandated that all clinical trials are registered on the website ClinicalTrials.gov within 21 days after the first participant is enrolled and that all results—positive or negative—get posted on ClinicalTrials.gov within one year of trial completion. (Groups can request two-year extensions if they are working with unlicensed products for which they are seeking regulatory approval.) Individuals who fail to comply could face monetary fines or suspension from NIH funding.

The changes coming in 2018 will affect the application process. Moving forward, all clinical trials will be funded by special announcements put out by NIH with specifically defined goals and design requirements. The objective is to limit the risk of funding studies that fail to produce usable data.

Too Soon to Assess Impact of Reforms

Wang, who was at the National Institute of Mental Health when these changes were first proposed, thinks they hit a good balance between meeting the needs of clinicians, researhcers, and the public.

“Clinical trial oversight is a complex issue,” Wang said. “And these changes are just the start toward changing a scientific culture where not reporting every result is still commonplace.” (Though APA did not comment on the expanded definition for clinical trials, the Association did release a position statement in 2015 endorsing participation in ClinicalTrials.gov. The statement also encouraged researchers to publish all study outcomes.)

It’s too soon to tell exactly how big an impact these changes will have on the scope and speed of clinical research; the first round of the new funding opportunity announcements were only recently released and the one-year deadline to report to ClinicalTrials.gov is just starting to come into effect. But, as Lauer noted, scientists have adapted to changes in how they are expected to report data before.

“Back in 2005, the editors of prominent journals like JAMA put out a rule that they would not publish clinical studies unless the trials were publicly registered,” he said. “A lot of people thought the sky was going to fall back then, but it didn’t happen.”

He noted that NIH has made many tools available online, such as a decision tree, hypothetical case studies, and an extensive FAQ. He also encouraged all investigators to reach out to program officials at their respective institutions to answer questions about how these changes could affect them. ■

More information on NIH’s definition of and requirements for conducting a clinical trial can be accessed here.