Magnetic Stimulation Can Reactivate Latent Working Memories

Abstract

While the findings demonstrate how short-term memories can be reactivated in healthy adults, it is not clear if the technique would lead to similar findings in people with compromised memory.

A common hypothesis about working memory—the ability to store and manage multiple short-term memories to complete a task—is that the neurons holding the relevant information need to be in an active state or else they will be erased.

A study published in Science on December 2, 2016, suggests that the brain can in fact store short-term memories in either an active or latent state, depending on whether those memories are immediately needed. This study of healthy volunteers also found that transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) appears to reactivate latent working memories.

Though this study was not designed with clinical applications in mind, the findings suggest that TMS could someday be used as a therapy for people with working memory problems.

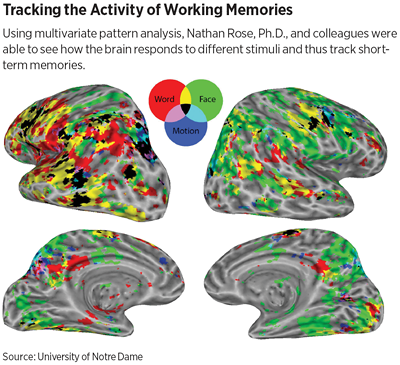

For this study, Nathan Rose, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Notre Dame and his colleagues observed the brain activity of healthy adults as they took a cued memory test. (Each participant was fitted with special headgear that enabled the researchers to visualize brain activity.)

Participants were asked to remember two distinct items that are processed differently in the brain, such as a word and a face. The two items appeared briefly on a screen, and then after a short delay a visual probe appeared on screen and the participant was asked if it matched one of the items they had been asked to remember. The first response was followed by another delay and a second probe.

After the two initial items flashed on screen, the researchers indicated to the participants whether a word or face would be evaluated first in the sequence. The idea behind this was to give the two items different levels of importance to see if that affected how the brain managed those memories.

The brain activity readings showed that when the two items appeared on screen, activity was elevated in the regions corresponding to each stimulus.

“When we cued someone to switch to a particular item, the activity for the other item dropped all the way to baseline, as if it had been forgotten,” said Rose. However, once the participant completed the first part of the test and was asked to recall that second item, neural activity related to that item became elevated again.

In another set of experiments, the participants performed the two-item memory test while Rose and colleagues applied TMS to the brain region corresponding to the unattended item after they gave the cue for which item would be tested first.

Applying TMS reactivated the memory of the unattended item. As a result, the participants were less able to reject probes related to the unattended item, said Rose, and would incorrectly state it was the cued item.

Rose noted that while the findings show how short-term memories can be manipulated, he cautioned that additional studies are needed to explore how the storage and retrieval of working memories change as people grow older or recover from an injury.

“There is a long way to go from investigating a basic question about memory in healthy adults to testing an intervention in adults with compromised memory,” said Rose.

Rose also pointed out that these studies used single pulses of magnetism that lasted a few seconds, whereas the TMS used in therapy known as repetitive TMS (rTMS) involves multiple pulses over a period of about 15 to 20 minutes. Rose told Psychiatric News that more studies are needed to evaluate the effects of rTMS on working memory. ■

An abstract of “Reactivation of Latent Working Memories With Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation” can be accessed here.