New Hampshire Hospital ‘Stays Safe’ Through Violence-Reduction Program

Abstract

Administration and staff have focused on “deconstructing” patients’ violent episodes to determine the variables surrounding those episodes.

It seemed to happen with a predictable regularity.

Staff at New Hampshire Hospital say the effort to address violence and aggression among patients requires collaboration between the administrative, clinical, and nursing staff; police and security officers; and researchers. From left are Lisa Mistler, M.D., M.S., Diane Allen, M.N., R.N., Alexander de Nesnera, M.D., and Lt. Frank N. Harris.

“Nora” was an inpatient diagnosed with a personality disorder at New Hampshire Hospital (NHH), a psychiatric hospital providing acute services for children and adults under the New Hampshire State Department of Health and Human Services. At a certain time of day, Nora began to decompensate, becoming restless, aggressive, and threatening to harm herself. Ultimately, she required seclusion or restraint.

“We called staff together for a case conference to look at the pattern of behavior that led to the decompensation and think about ways to get the patient motivated at that period of day and involved in certain activities, or to get her off the unit if that was necessary,” said Alexander de Nesnera, M.D., associate medical director at NHH and an associate professor of psychiatry at Dartmouth University’s Geisel School of Medicine.

“A decision was made to have two staff members accompany her away from the inpatient unit and to the hospital gym,” he said. “By intervening in this way, we could break the cycle of decompensation before it happened and protect the patient and the staff.”

Training Elements

“Staying Safe” is an educational program implemented at New Hampshire Hospital to change the culture around dealing with aggressive patients—especially the prevalent belief among staff that getting hurt is just one aspect of their job experience.

“Getting hurt is not an expected part of the job of caring for psychiatric patients,” Diane Allen, M.N., R.N., told Psychiatric News.

Program leaders challenged the belief among staff that it is their job to be “superheroes” and disregard their own safety to protect patients and other staff.

A total of 245 direct care staff attended 20 in-house classes from January to April 2009. A training specialist, nurse educator, and nurse leader worked together during the two-hour program to establish an open forum for discussion. At least six program messages emerged for nurses and other staff providing direct care to potentially aggressive or violent patients:

Be respectful.

Avoid power struggles.

Prepare for bad news.

Evaluate unit rules.

Get help from at least five people before physically intervening with patients.

“Strategies that have helped reduce assaults to staff include getting enough help and having a plan before physically intervening with patients,” Allen said. “It makes sense if a patient is becoming violent to have five people help you—one person for each limb, and one person who can talk to the patient.

“We also discussed evaluating unit rules that cause patients frustration and stress and how to share bad news—such as if direct care staff are unable to answer when a patient is allowed to go home.”

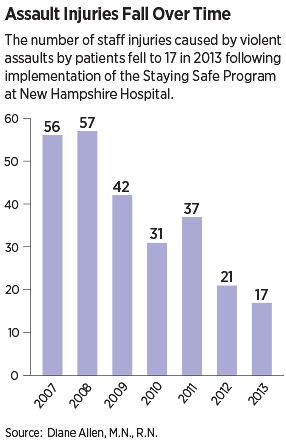

The program has been successful: the number of staff injuries resulting in lost work time from assaults fell from a high in 2008 of 57 to just 17 in 2013 (see chart on facing page).

The program continues today as part of orientation for new employees.

“We still meet at a standard time each week day to discuss any incidents of violence,” Allen said. “We now have incorporated standardized data collection [about violence] into our routine paperwork. Now that we are moving toward electronic health records, we have been building our e-forms by adding questions about violence and aggression to the documentation that nurses complete every shift.”

It’s an example of the effort de Nesnera and staff at NHH have made to address a problem that administrators, psychiatrists, and nursing staff on psychiatric inpatient units everywhere will recognize: the threat of violence and aggression on the part of patients that is directed at staff and associated with seclusion or restraint.

The initiative at NHH is comprehensive and involves administration, psychiatrists, nursing staff, law enforcement personnel, and community leaders. The effort also includes an ongoing research initiative designed to systematically gather data on aggression and violence, physical and verbal assaults and injuries, and variables associated with the occurrence of assaults.

In an interview with Psychiatric News, de Nesnera said the effort began in a formal way around 2008 and resulted from a “perfect storm” of factors also familiar to psychiatric administrators and staff: increasing demand and decreasing capacity for psychiatric care in the surrounding community, an influx of sicker, more complex patients frequently with substance use disorders in addition to mental illness, and forensic patients coming from secure psychiatric units in jails and prisons.

“Gradually we saw that we needed to address the issues associated with increasingly challenging patients with co-occurring disorders coming from a variety of settings,” he said. “We knew we needed to work comprehensively with staff and with community institutions and administrative entities before this challenge became a real crisis.”

Deconstructing Violent Episodes

“Nora” and patients like her who become agitated and potentially violent can be subdued with seclusion or restraint, but as de Nesnera says, “Seclusion or restraint is an emergency measure, not a treatment intervention.”

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has issued a number of “issue briefs” and other resources on reducing and eliminating seclusion and restraint. SAMHSA notes that these measures can result in psychological harm, physical injuries, and death to patients and to staff. Rates of injury to staff in mental health settings that use seclusion or restraint have been found to be higher than rates of injuries sustained by workers in high-risk industries.

“In the early 2000s, there was a national effort to reduce seclusion and restraint,” said Diane Allen, M.N., R.N., assistant director of nursing for acute psychiatric services at NHH. She told Psychiatric News it was after a SAMHSA training session on the subject that staff at NHH decided to track and record the episodes that resulted in seclusion or restraint (and very often in injuries to patients and/or staff). “We decided we were going to elevate these events, make them visible for higher levels of review—for supportive reasons, but also so we could learn more about the root causes.”

Allen and de Nesnera initiated regular meetings involving administrative leaders, psychiatrists, and nursing staff to discuss incidents of verbal or physical violence. “We emphasized that these meetings would not be about criticism or second guessing what people did—otherwise, no one was ever going to come,” she said. “Rather, our approach was, ‘Tell us what happened.’ ”

Out of these discussions emerged certain patterns associated with violence: inadequate treatment of patients’ symptoms of paranoia or hallucinations, patient frustration with hospital rules, inconsistencies in protocols between different units, or the receipt of bad news.

In particular, Allen said, troubling news was a trigger. Patients would learn, for example, that they had lost their job, their wife had left them, or there was no one to take care of their dog

Interactions with civil courts were also liable to be a trigger. “We learned that the highest number of episodes requiring seclusion or restraint fell on Tuesday—which is the day our patients appear in court,” Allen said. “One of the features of court hearings is that a judge may tell patients that they will hear some resolution of their case by the end of the day. Often that doesn’t happen, and patients become extremely angry and agitated. So we talked to judges and educated them about giving patients realistic expectations about when they may or may not hear a resolution to their case.”

Police Regarded as Friendly Presence

From the findings that emerged out of case consultations, Allen and staff developed a strategy called “Staying Safe,” built around a model of staff and patient safety described by Robert Short, Ph.D., and colleagues in the 2008 Psychiatric Services article “Safety Guidelines for Injury-Free Management of Psychiatric Inpatients in Precrisis and Crisis Situations” (see chart on the left).

If “Staying Safe” was the on-the-ground strategy for reducing the threat of violence and injury to patients and hospital staff, there was a broader administrative strategy at NHH of reaching out to and working with institutions in the wider community to deal with systemic problems.

This included developing procedures for patients being “stepped down” from secure psychiatric units in jails or prisons (many of whom had been deemed not guilty of a crime by reason of insanity). Importantly, it also included working with hospital security police to create a “community policing” atmosphere on the unit, so that officers were regarded by patients as a familiar, benign presence—as opposed to a threatening and punitive one.

“Patients got to know the police officers in the friendly way that people in the community may get to know an officer who is regularly on the street,” de Nesnera said.

Additionally, de Nesnera and colleagues reached out to other state psychiatric hospital administrators in New England—including state hospitals in Maine and Vermont—to trade information and strategies for handling violent episodes. “We were able to share our experiences as to what it is like dealing with violent patients or with particular policies that were cumbersome,” de Nesnera said. “The ability to share our experiences and our expertise was really important and engendered a sense that we are all in this together.”

Tackling the problem of violence on inpatient psychiatric units requires hospital administrators to view the “big picture” while also being willing to work incrementally. You don’t have to reform the entire correctional system, de Nesnera suggested, but reaching out to educate one judge in the community—about mental illness, antisocial behavior, and hospital staff safety—can accomplish a lot.

“Administrators need to have a broad knowledge of the multiple systems working—sometimes together, sometimes not—on various aspects of mental health care for individuals,” he said. “But they should start with the ‘low hanging fruit’ to begin addressing systems issues that impede appropriate treatment of mentally ill patients. Once you do that, you can begin to work on the bigger problems.” ■

“Best Practices: Safety Guidelines for Inju-ry-Free Management of Psychiatric Inpatients in Precrisis and Crisis Situations” can be accessed here.