Match Madness: Educators Call Frenzy of Applications Bad for GME

Abstract

Some specialties have become extremely competitive, pushing graduates to apply to large numbers of programs in the hopes of matching. But candidates for psychiatry need not be so anxious.

Has the annual “Match Day” in March—when graduating U.S. medical students are matched into residency training programs—turned into Match Madness?

Educators at medical schools and training programs across disciplines say it has: graduates—driven by acute anxiety about being accepted into a training program after having already accumulated considerable medical school debt and the perception of greatly heightened competitiveness—are applying to and interviewing at more and more programs.

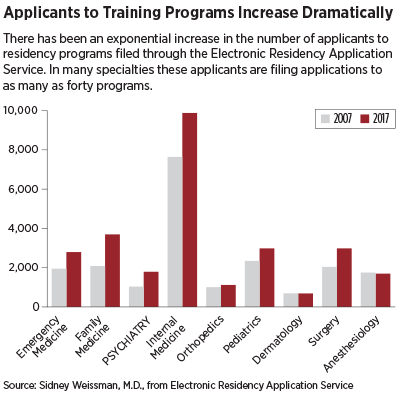

Statistics from the Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS), through which students can apply to programs online, document an exponential growth in applicants to residency programs in the last decade (see chart). Between 2007 and 2017, the number of applicants to psychiatry training programs has increased 73 percent.

It is a phenomenon that creates enormous stress for students while complicating the task for residency programs of selecting appropriate candidates. Meanwhile, the frenzy of applying to and interviewing for residency slots wreaks havoc on the fourth year of medical schooling.

“My daughter is in her fourth year of medical school and interviewed at 12 programs,” said Gregory Briscoe, M.D., president of the Association of Directors of Medical School Education in Psychiatry. “That’s remarkable to me—when I was a resident I interviewed at a handful of programs. I have heard our own medical school students [at Eastern Virginia Medical School] complain about it—it’s a huge burden in terms of time, travel, and expense. And it erodes education in the fourth year to some extent.”

The phenomenon was the subject of an article in Academic Medicine in November 2016 titled “Residency Placement Fever: Is It Time for a Reevaluation?” The authors, Philip A. Gruppuso, M.D., and Eli Y. Adashi, M.D., M.S., wrote, “This development represents a maladaptation that serves neither applicants nor GME programs. The undergraduate medical education enterprise appears to be similarly compromised.”

‘Perfect Storm’ of Factors at Play

Sidney Weissman, M.D., a former president of the American Association of Directors of Psychiatric Residency Training and a former APA trustee, described a perfect storm of factors influencing the phenomenon: the increase in the number of applicants caused by the creation of new medical schools, larger class sizes, and a growing number of international medical graduates (IMGs)and graduates of osteopathic schools has exceeded the increase in the number of residency positions.

“AAMC data suggest that the number of U.S. medical graduates is increasing by 3 percent a year and the number of residency positions by 1 percent,” he said. “This fuels the increase in applications by students and also has the effect of making it increasingly difficult for IMGs and for students wishing to change fields to obtain positions.”

(Funding of graduate medical education through the Medicare program has been capped since 1997, freezing the number of training positions at institutions funded with federal dollars. Programs that had not previously received federal funds are eligible for new federal dollars, but these programs account for only a small increase in the number of residency slots. Some funding to support more positions is supplied by states and—in rare instances—individual hospitals.)

Weissman noted that last year 1,130 seniors did not match into a program, and after the Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program (SOAP), 615 still did not have positions. “It is anticipated that the numbers will be similar this year,” Weissman said. “All students feel the need to ensure that they match, so they are applying to multiple programs, including specialties they regard as a default—in the same way that applicants for undergraduate colleges have a ‘safe school.’ ”

He said some students are sending applications to as many as 40 programs—a staggering number to older physicians who remember applying to only a few—and interviewing at 10 to 15 or more.

Psychiatry Candidates: Relax

Trustee-at-Large Richard Summers, M.D., past chair of the council on Medical Education and Lifelong Learning, says there are either no, or very few, American medical graduate applicants who are qualified for and seek a residency in psychiatry who don’t match.

Trustee-at-Large Richard Summers, M.D., past chair of the council on Medical Education and Lifelong Learning, said “Match Madness” is a problem that troubles medical educators everywhere. But for graduates who are truly interested in psychiatry (as opposed to merely applying to psychiatry programs as a default), he offers a nuanced interpretation of what is happening to the Match process and some advice: relax.

Summers told Psychiatric News that the frenzy of applying and interviewing is at least in part “a self-propagating” one. The threat of not finding a match position is certainly true for a handful of highly competitive specialties—surgery, orthopedics, dermatology, and anesthesiology, Summers said.

But in psychiatry—as in family practice, internal medicine, pediatrics, and ob-gyn—there has been a slight increase in competitiveness, but nothing that justifies applying to 40 programs.

“That’s unbelievable,” Summers said. “People should be applying to 15 programs, maybe. It’s a measure of the anxiety felt by students. It’s onerous and expensive for students to be flying off to multiple interviews and hugely preoccupying in a way that diminishes the fourth-year experience.”

It is also a burden for training programs. “The volume of applications imposes on the program an imperative to find an inevitably non-rational way to sort out who they are going to interview, with the result that a lot of excellent people may get overlooked,” Summers said.

He traces the problem to the fact that rates of students matching into training programs have become a metric by which medical schools are evaluated. Consequently, medical school leaders have—rationally from their perspective—assumed an urgent responsibility to make sure that all of their graduates find a match. For that reason, deans and advisors have communicated the message that students should apply to as many programs as possible.

Meanwhile, ERAS has made filing an application relatively inexpensive and easy, so graduates responding to the global perception of competitiveness can apply to multiple programs. (The total cost of applying to 30 programs is $379; each additional application is $26.)

“The increased number of applications per applicant in psychiatry seems to be a result of the medical schools and deans spreading the word that the residency match overall is more competitive,” Summers said. “But, this is only barely true about psychiatry. My impression is that there are either no, or very few, American medical graduate applicants in psychiatry who are qualified for the field but who don’t get spots.

“But there has been a creep in everybody’s thinking because of the perception that the Match overall, in every specialty, has gotten more competitive,” he said. “The unintended consequence is that all applicants are now feeling much more anxious about the possibility of not matching.”

It’s an educational problem, Summers said, that could be resolved by more careful communication by deans and advisors to graduates about the specialties in which they may need to be especially aggressive in the application and interviewing process.

“Other solutions are cruder and would probably not be popular—including capping the number of applications or applying a progressively more expensive fee for applications,” Summers said. ■

“Residency Placement Fever: Is It Time for a Reevaluation?” can be accessed here.