Preparedness Helps MH Professionals Cope With Hurricane Florence

Abstract

No one waited for the slow-moving storm and its heavy rainfall to arrive before taking action to help patients with mental illness.

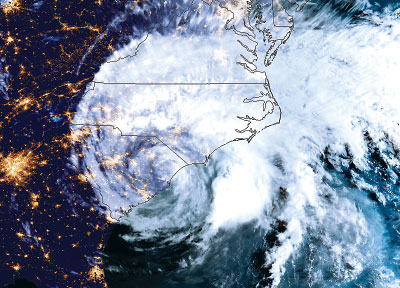

The mental health response in the Carolinas to Hurricane Florence began long before the storm hit the Atlantic shore on September 14 and then dumped up to 36 inches of rain inland.

A series of hurricanes has struck North and South Carolina in recent decades, and disaster officials in the region have learned a lot from the experience. Being ready is critical. Hurricane Matthew’s $1.6 billion devastation in 2016 simply spurred an existing trend toward advance preparation rather than merely reacting after each disaster.

Even so, Florence’s effects in North Carolina were particularly complex, said Allan Chrisman, M.D., an emeritus associate professor of psychiatry at Duke University in Durham and disaster chair of the North Carolina Psychiatric Association (NCPA) since 2010.

“The immediate impact on the coast came from wind, rain, and the storm surge on the coast,” said Chrisman in an interview. “Then the storm moved inland, and heavy rains flooded rivers and hog waste lagoons, which washed downstream, bringing chemical and bacterial contamination.”

North Carolina is considered a well-prepared state for natural disasters, and Chrisman participates in a disaster mental health response network managed by the local affiliate of the American Psychological Association. The group also includes social workers, marriage and family counselors, Red Cross mental health representatives, and state disaster officials. They all take part in regular training sessions under a state master plan, while local mental health managed care organizations also conduct training.

“Those organizations also did a terrific job of recruiting local providers to work in shelters,” said Chrisman.

NCPA Acted on Pre-Storm Plan

The NCPA also did its part before the storm, placing links to a variety of hurricane resources on its website. Topics included postdisaster mental health, psychological first aid, local emergency contacts, and Medicaid response and recovery. NCPA members in the hurricane’s path were sent text messages, reminding them of the association’s availability to help.

“Now, we want to upgrade our member database to be sure we have cell phone numbers and then rationalize our text-messaging communications,” said NCPA Executive Director Robin Huffman, after the storm.

Joshua Morganstein, M.D., chair of APA’s Committee on the Psychiatric Dimensions of Disaster and an associate professor of psychiatry at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences (USUHS) in Bethesda, Md., sent a link to a webpage produced by USUHS’s Center for the Study of Traumatic Stress. The site offered “brief, actionable information on important disaster mental health issues related to this hurricane.”

“Hurricane Matthew reminded us of two things: the need for good communications and maintaining access to resources,” said Chrisman in an interview.

Before and after Florence, for instance, the mental health managed care organizations and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams worked together to check on the availability of medication supplies.

ACT teams in Wilmington, N.C., where the storm hit hardest, prepared special hurricane plans for each patient, including a list of shelters and emergency phone numbers, along with a checklist of recommended supplies, reported Christopher Myers, M.D., in an email to NCPA headquarters. “For this particular storm, we made sure each patient had two weeks of medications in blister packs and checked with those not receiving blister packs to ensure they had at least two weeks of medications.”

Sometimes that required alerting pharmacies and Medicaid officials for the need to override usual rules and grant an additional 72-hour supply of naloxone and other medications to patients. The recent increase in use of long-lasting injectable medications in psychiatry meant that those drugs needed to be provided in shelters. NCPA members working in shelters often used their general medical skills to triage patients for appropriate care.

Technological improvements over the years have helped as well, said Kaye McGinty, M.D., a professor of psychiatry at East Carolina University in Greenville. She recalled Hurricane Floyd in 1999, which also produced heavy flooding.

“That was before electronic health records and before Medicaid was computerized in the state,” said McGinty. Some mental health centers were flooded, and records were lost.

“We were operating out of a trailer and begging for medication samples,” she said. “It was chaos. This time, the systems were really ready, helped by the availability of online medical records.”

McGinty also works with children in state schools for the visually impaired and the deaf. Dealing with a storm is more challenging for students with mild intellectual disabilities, because they know something is happening but may not know what to do. She spent the Monday before the storm educating students about how to remain safe. For many, that meant returning home. “In any case, be with others, not alone,” she told students. “Know your physical surroundings by getting help exploring new settings, like shelters.”

Similar Response in South Carolina

South Carolina was not hit as severely, but the South Carolina Psychiatric Association (SCPA) quickly sent out preparedness information to its members. That included providing resources to use with patients plus some self-care guidance for responders and caregivers, while encouraging members to plan for themselves and their families.

“We shared some online resources with our membership and asked for updates from those impacted or involved in helping others,” said SCPA President Jeffery Raynor, M.D. “Psychiatrists are spread rather thin in our state, with concentrations in places that ended up being less affected by the storm and subsequent flooding in other places like Greenville, Columbia, and Charleston.”

“Part of the recovery process is helping colleagues and trainees understand that preparation and team standby are critical, even when we wound up with virtually nothing in Charleston,” said Edward Kantor, M.D., an associate professor and the residency director for psychiatry at the Medical University of South Carolina and the SCPA’s chair for disaster psychiatry. “Rescues and supporting displaced people are the early priorities. For the district branch, one of our early recovery efforts is to try to see if members are safe and if they or their practices were affected.”

As in every disaster, the psychological effects on storm victims are held at bay for a time by the need to focus on more immediate needs.

“We’re just at the beginning of this,” said NCPA’s Huffman. “Once the roads are cleared and the TV reporters leave, that’s when the real work begins. The longer-term adverse effects will be the problem.” ■