FDA Clears First Direct-to-Consumer Pharmacogenetic Test

Abstract

23andMe’s Personal Genome Service now offers data on an individual’s ability to metabolize drugs, which may or may not be useful in clinical decision making.

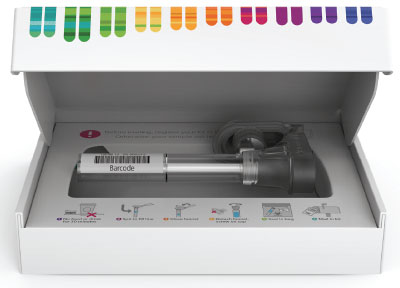

In October, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized the DNA-testing company 23andMe to begin marketing the first direct-to-consumer pharmacogenetic test. This clearance marks another major advance in the field of personal genomics, but some experts caution that such tests may offer very little medical value.

Unlike DNA tests that assess patients for genetic variants linked with risk of getting a disease—such as the BRCA gene and breast cancer—pharmacogenetic tests indicate a person’s ability to metabolize medications; that is, do they stay in their body longer or shorter than average?

Specifically, 23andMe’s Personal Genome Service Pharmacogenetic Reports test looks for 33 possible variants among eight genes that encode metabolic proteins. The list includes four members of the cytochrome P450 family—a group of enzymes that does the lion’s share of the body’s drug metabolism duties. Many psychotropic drugs, including commonly prescribed antidepressants and antipsychotics, are targets of P450 proteins.

The FDA authorization allows 23andMe “to provide customers with information on whether they are predicted to be fast or slow metabolizers based on their genetics, but does not describe associations between any detected genetic variants and any specific medication,” the company noted in a press release.

This is an important distinction, said Anne-Marie Dietrich, M.D., a private practice psychiatrist in Alexandria, Va., who uses pharmacogenetics in her practice. (Tests designed for physicians have been available for years). “[T]hese tests can tell someone only how they are going to metabolize a medication, not how they will respond to a medication.”

Still, even though the information is limited, Dietrich told Psychiatric News that these consumer tests can provide useful information to psychiatrists.

“If a patient provided me with their pharmacogenetic profile, I would look at it alongside other lab tests, patient and family history, and a patient’s previous medication trials when making a decision,” she said. “And I have adjusted patient medications based on pharmacogenetic data. It is important that physicians do not put too much stock in these tests [alone].”

Charles Nemeroff, M.D., Ph.D., a professor of psychiatry at the Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin, told Psychiatric News that the potential risks of 23andMe’s test lie in patients’ deciding to alter their adherence to medication based on the genetic information. Some people who order the tests may interpret test results to mean they should stop or increase their medications based on their results, he explained.

As part of the marketing clearance, the FDA established some special requirements to ensure patient safety, including that the test’s label include appropriate warning statements that medication changes should only be made after discussing test results with a licensed health care professional who can confirm the results with a clinical test. As part of the clearance requirements, 23andMe reported that 97 percent of customers understood the caveats about pharmacogenetic testing.

Even if used properly, these tests do not yet make much economic sense in psychiatric practice, Nemeroff continued.

“The FDA approval was focused on the genetic tests being helpful in preventing potential adverse drug effects,” he said, noting that understanding a patient’s metabolic information could prevent doctors from dosing patients too high. “This is not really an unmet need when prescribing drugs like antidepressants. By starting with a low dose and gradually increasing it, we avoid side effects in patients who cannot tolerate higher doses.”

The more pressing need is getting information that may help physicians to pick which antidepressant might provide the best chance of response, Nemeroff said. But as APA’s Task Force for Novel Biomarkers and Treatments, which is chaired by Nemeroff, noted earlier this year (Psychiatric News, July 19, 2018), current pharmacogenetic tests fall short in that regard.

“If a patient wants to get one [a personal genomics test], they certainly can as an independent consumer, but I would recommend they bring the results to an experienced psychopharmacologist to help with the interpretation,” he said. ■