Survey Finds Dramatic Disparities in Reimbursement, Out-of-Network Use

Abstract

APA leaders say the findings prove that insurers are wrong when they claim that lack of access to mental health/substance use treatment in provider networks is caused by the shortage of psychiatrists.

Psychiatrists are paid significantly less than general medical and surgical physicians providing the same or similar services, according to a groundbreaking report published last month by Milliman Inc. The analysis, commissioned by the Bowman Family Foundation, also found that patients’ use of out-of-network services is extremely high for behavioral health compared with general medical and surgical services.

Together, the findings paint a stark picture of restricted access to affordable and much-needed treatment for mental illness and substance use disorders. APA leaders said that the findings are especially alarming in an era of escalating suicide rates and opioid overdose deaths. “The result,” said APA CEO and Medical Director Saul Levin, M.D., M.P.A., “is an unequal health care system for patients with mental illness or substance use disorders.”

Milliman analyzed insurance claims data for 42 million Americans from 2013 to 2015, comparing provider reimbursement for services and use of out-of-network services in all 50 states and the District of Columbia. The firm relied primarily on two large, national research databases for this analysis: Truven MarketScan Commercial Claims and Encounters Databases and Milliman Consolidated Health Cost Guidelines Databases.

The Truven and Milliman databases reflect health service utilization by employees and dependents covered by the health benefit programs of large employers and government organizations. The analysis found that general medical and surgical physicians were paid rates an average of 20 percent higher than those of psychiatrists for the same office visits billed under identical or similar codes.

The two most commonly billed services for office visits are “evaluation and management” (E/M) visits for patients involving a low or moderate level of complexity of care. (The CPT billing codes for these are, respectively, 99213 and 99214.) Because the Medicare-allowed amounts for these services do not vary by type of physician, the payment levels provided for these services offer the most direct apples-to-apples comparison between the payment levels of primary care, medical/surgical specialist physicians, and psychiatrists.

Primary care and general medical/surgical specialist physicians were paid, respectively, 20.6 percent and 14.1 percent higher for low complexity E/M visits than psychiatrists and 20.0 percent and 17.8 percent, respectively, higher for moderate complexity E/M visits.

Key Points

An analysis of claims data for 43 million Americans shows dramatic differences in reimbursement rates and use of out-of-network services for primary care physicians, medical/surgical specialist physicians, and psychiatrists.

Primary care and medical/surgical specialist physicians were paid rates an average of 20 percent higher than those of psychiatrists for the same services billed under identical or similar codes.

Primary care and medical/surgical specialist physicians were paid on average 15.2 percent and 11.3 percent higher, respectively, than Medicare-allowed amounts, while psychiatrists were paid on average 4.9 percent less than Medicare-allowed amounts.

On average, 18.7 percent of behavioral health office visits were to out-of-network psychiatrists in 2015, while just 3.7 percent of medical/surgical office visits were out of network.

Bottom Line: The findings paint a stark picture of insurance company restrictions on access to affordable treatment for mental illness and substance use disorders.

In 2015 alone, there were 24 states with reimbursement disparities between general medical physicians and psychiatrists ranging from 30 percent to 69 percent, according to the report.

To account for differences in the mix of services provided by different physicians, Milliman also examined payment rates relative to the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule in each year for the same services. In 2015, primary care and medical/surgical specialist physicians were paid on average 15.2 percent and 11.3 percent, respectively, higher than Medicare-allowed amounts, while psychiatrists were paid on average 4.9 percent less than Medicare-allowed amounts.

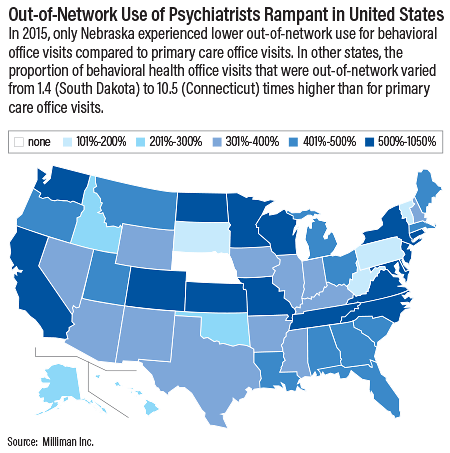

Additionally, Milliman found extraordinary discrepancies in the use of out-of-network providers. On average, 18.7 percent of behavioral health office visits were accessed out of network in 2015, while just 3.7 percent of primary care and medical/surgical office visits were accessed out of network. Moreover, 16.7 percent of inpatient facility behavioral health care was accessed out of network compared with just 4 percent of inpatient facility medical/surgical care.

In 2015, out-of-network use of behavioral health inpatient care compared with that of general medical and surgical care was approximately 800 percent higher in California, New York, and Rhode Island and over 1000 percent higher in Connecticut, Florida, New Hampshire, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania (see map).

Levin said the findings are evidence of a pattern of behavior by insurance companies that is forcing patients to use costly out-of-network care. The result is that many patients have limited access to care and may abandon treatment altogether because they cannot afford it. In addition, the findings point to potential violations of federal and state parity laws, which require insurance companies to cover treatment for mental illness and substance use at the same levels as for other medical illnesses.

“This report echoes what APA has been saying for the past several years—that insurers are not maintaining adequate networks of psychiatrists for patients and that psychiatrists are reimbursed less than primary care doctors for the same services,” Levin said. “We have been actively fighting payment disparities and demonstrating the inadequacy of networks to attorney generals, insurance commissioners, legislators, and insurance companies. We will incorporate the information in this report as we continue our advocacy.”

APA and nine other mental health advocacy groups issued a statement in response to the report calling for the following steps:

Federal regulators should issue more specific guidance on medical management practices by insurance companies and initiate audits of major insurers.

Employers should retain independent companies to conduct audits of insurance company compliance with parity, reimbursement tracking, out-of-network use, rates of claim denials, and other variables related to access to benefits.

State agencies should conduct routine annual market audits of all insurers in their state for compliance with parity.

The other groups include Parity Implementation Coalition, Mental Health America, National Alliance on Mental Illness, Kennedy Forum, National Association of Addiction Treatment Providers, American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Treatment Advocacy Center, National Association of Psychiatric Health Systems, and Legal Action Center.

APA President-elect Altha Stewart, M.D., said the report demonstrates the fallacy of insurance company claims that the shortage of psychiatrists is to blame for lack of access to care in networks.

“The out-of-network data demonstrate that there are psychiatrists available and seeing patients, just not within the insurers’ networks,” she told Psychiatric News. “It is up to insurers to do something to improve the adequacy of their networks so that patients get the care they have paid the company to provide.”

Stewart said the insurance companies could start with an “equal pay for equal work” concept and remove many of the administrative hurdles psychiatrists face when trying to help patients access care.

“The unpaid administrative time in combination with substandard reimbursement rates is among the causes that drive psychiatrists away from networks,” she said. “Additionally, when psychiatrists do not face hours a day of administrative time, they have more time to spend with patients, and access to care is improved.” ■

“Addiction and Mental Health Versus Physical Health: Analyzing Disparities in Network Use and Provider Reimbursement Rates” can be accessed here.