California Ruling May Negatively Impact University Policies on Mental Illness

Abstract

The ruling in Rosen v. Regents applies only to California, but courts in other states are liable to take notice because of widespread concern about violence on campus.

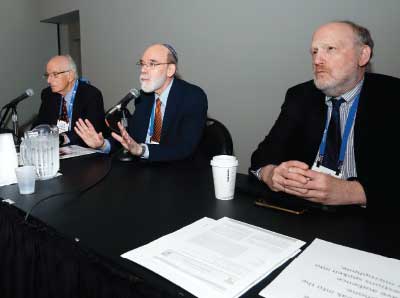

Paul Appelbaum, M.D., notes that the University of California told the court its ruling could cause colleges not to provide mental health treatment. “It’s the ‘see no evil’ defense.” Flanking Appelbaum are Howard Zonana, M.D., and Marvin Swartz, M.D.

Do colleges and universities have a responsibility to protect students from violence that may be perpetrated by other students with mental illness?

That’s the question at the heart of a recent California Supreme Court ruling. This past March, the California Supreme Court found that students have a reasonable expectation that universities will provide a safe environment in classrooms and laboratories, including protection from violence perpetrated by students who may be mentally ill.

At a symposium at APA’s 2018 Annual Meeting in New York, past APA President Paul Appelbaum, M.D., said that although the ruling in Rosen v. Regents of the University of California applies only to institutions in California, it is likely to be looked at with interest by other states where colleges and universities are concerned about violence on campus.

The effect of the ruling on how colleges and universities may view students and applicants for admission who have a history of mental illness is unknown. “The concern is that it will heighten universities’ attention to troubled students—not in a good way—and make them less willing to admit, retain, or re-admit them,” said Appelbaum, who is also the Dollard Professor of Psychiatry, Medicine, and Law and director of the Division of Law, Ethics, and Psychiatry at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons. “Student mental health services may face greater pressure to identify ‘risky’ students, and students may be more likely to withhold information about mental health treatment or avoid campus mental health services altogether.”

APA Seeks to Protect Rights of People With Mental Illness Through the Courts

APA has offered its opinion on at least two other prominent cases addressing standards for assessing intellectual disability and the duty of correctional facilities to provide discharge planning.

In Charles v. County of Orange, Michelet Charles and Carol Small alleged their due process rights were violated when a civil immigration detention center failed to provide them with discharge plans for treatment of their mental illness.

The Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York disagreed, but Charles and Small have appealed the decision.

In its brief, APA and six other groups noted that discharge planning is essential. “We argued that evaluation of a constitutional claim must give adequate weight to the consensus among mental health professionals that appropriate discharge planning is a critical part of the minimally adequate mental health care that the Constitution requires,” said Marvin Swartz, M.D., chair of APA’s Committee on Judicial Action and head of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine. A May 2017 ruling by the Supreme Court in Moore v. Texas is the latest in a long-running case involving Bobby James Moore, incarcerated for a murder he committed in 1980. In 2002, Moore claimed he could not be executed for the crime because he was intellectually disabled, citing the landmark case Atkins v. Virginia of that same year in which the Supreme Court held that the execution of intellectually disabled individuals violates the Eighth Amendment.

Two years later, a Texas court of appeals adopted its own idiosyncratic standards (known as “Briseño factors” for the case Ex parte Briseño) for determining intellectual disability that were regarded by APA and other professional groups as wholly unrelated to clinically accepted standards (Psychiatric News, January 3, 2017).

APA stated in its brief: “In assessing whether an individual meets the clinical definition of intellectual disability, this Court should recognize the unanimous consensus among the mental health professions that accurate diagnosis requires clinical judgment based on a comprehensive assessment of three criteria: general intellectual functioning; adaptive functioning in conceptual, social, and practical domains; and onset during the developmental period. Failure to follow a diagnostic approach guided by these principles would violate applicable professional standards and create an unacceptable and significant risk that individuals with intellectual disability may be executed in violation of the Eighth Amendment” and the Supreme Court’s ruling in Atkins.

The Supreme Court agreed and vacated the court of appeals’ judgment, stating that adjudications of intellectual disability should be “informed by the views of medical experts.”

Moreover, the court said that the several factors Briseño set out as indicators of intellectual disability are “an invention of the [court of appeals] untied to any acknowledged source.”

The court remanded the case back to the court of appeals, and last October APA submitted another brief reiterating its position on how to do appropriate assessments and identifying new standardized instruments for assessing adaptive functioning.

Appelbaum was joined at the symposium by Howard Zonana, M.D., a professor of psychiatry and adjunct professor of law at Yale University, and Marvin Swartz, M.D., chair of APA’s Committee on Judicial Action, which organized the symposium. Swartz is also head of the Division of Social and Community Psychiatry at Duke University School of Medicine. The panelists discussed separate cases addressing the question of whether correctional facilities have a responsibility to provide discharge treatment planning for released detainees who have mental illness and the standards that should be applied to determine intellectual disability in cases involving the death penalty. In each of these cases, APA submitted an amicus brief.

Rosen v. Regents may have the broadest impact. In fall 2008, Damon Thompson transferred to the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Not long after, he began to complain—to professors and others—that other students were making derogatory comments about him. He later wrote a letter to the dean of students saying that students in the dorm were making unwelcome sexual advances, spreading rumors, and teasing him. He warned that if something wasn’t done, the situation would “escalate.”

He was moved to a new dorm, but the following semester his complaints continued. In February 2009 he complained of hearing voices coming through the dorm walls calling him an “idiot.” He also claimed to hear students “clicking” guns in a threatening way. When campus police arrived, he was taken to the emergency room and diagnosed with schizophrenia. Thompson agreed to take a low dose of an antipsychotic medication and was referred to the campus mental health service, where he was evaluated by a psychiatrist and had several sessions with a campus psychologist.

However, in March 2009 he threw away his medication and a month later withdrew from treatment. The following September he returned to campus and told a chemistry lab professor that other students were interfering with his experiments. On October 7, the director of campus mental health met with the dean of the school and a campus crisis response team to discuss what to do about Thompson. But the following day, he attacked the student next to him in the laboratory, Katherine Rosen, stabbing her in the chest and neck with a kitchen knife.

Rosen was seriously injured but survived. She sued the university, dean of students, chemistry professor, and psychologist alleging negligent failure to protect, warn, or control the attacker. UCLA moved to dismiss the case on the grounds that colleges have no duty to protect adult students from criminal acts and made a motion to dismiss. A trial court denied the motion, and an appellate court granted the motion. Also, the court found the psychologist exempt from liability because the California statute requires that there be an explicit threat made against a specific person.

The case went to the state Supreme Court. The amicus brief filed by APA, the California Psychiatric Association, and the California Association of Marriage and Family Therapists was confined to the relatively narrow issue of supporting the psychologist’s exemption from liability. That exemption was upheld by the Supreme Court.

However, the court ruled that “a special relationship” exists between a university and its students and that students have a reasonable expectation that universities will provide a safe environment in classrooms and laboratories. That duty applies when harm from a particular student is reasonably foreseeable in a curricular setting.

Appelbaum explained that the broader implications of the court’s ruling have to do with how universities and colleges may regard students with a history of mental illness. “UCLA argued that colleges would have an incentive not to provide extensive mental health services,” Appelbaum said. “It’s the ‘see no evil’ defense—if you don’t provide services, you can’t know that someone might be a threat, and you can’t be held liable. The university also claimed colleges would be more likely to suspend or expel students with mental illnesses.”

Appelbaum said the court dismissed these concerns, saying the Americans With Disabilities Act and “market forces” would constrain colleges from discriminating against students with mental illness.

“It remains to be seen how that will play out,” he said. “The court’s ruling is limited to California, but it may influence courts in other states.” ■

APA amicus briefs can be accessed here.