Study Suggests Chronic Opioid Use Linked to 2016 Presidential Voting Patterns

Abstract

Counties with greater long-term opioid use and more socioeconomic hardships were more likely to vote for Trump in the 2016 election.

Counties with higher prescription opioid rates were more likely to support candidate Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election, according to an analysis of Medicare claims published in JAMA Network Open.

Public health policy directed at stemming the opioid epidemic must go beyond the medical model that focuses on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment protocols. —James Goodwin, M.D.

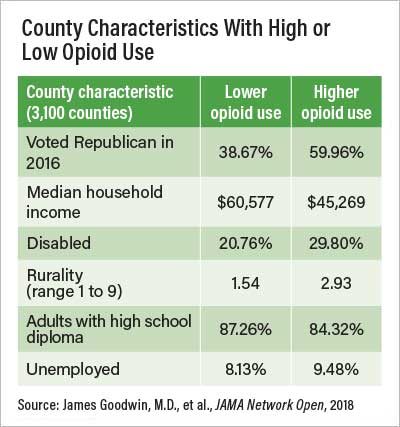

In U.S. counties with the highest long-term opioid prescription rates, the Republican presidential candidate averaged 60 percent of the vote versus nearly 40 percent of the vote in counties with lower rates, the study found.

The study sought to shed light on the socioeconomic causes of the opioid epidemic that are believed to be associated with the overlap between the 2016 presidential vote and the opioid prescribing rate, explained James Goodwin, M.D., chair of geriatric medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

For the study, Goodwin and colleagues studied data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the 2016 presidential vote, and a national sample of nearly 3.8 million Medicare Part D enrollees’ 2015 claims. They determined each county’s rate of prescription for a 90-day or greater supply of opioids in 2015. They found that socioeconomic indicators—including disability, unemployment, attainment of a high school diploma, and degree of rurality—explained about two-thirds of the association between the presidential vote and opioid use.

“Here we have areas of high poverty and high unemployment—areas that have been left out of socioeconomic improvement, left out of the American success story,” Goodwin told Psychiatric News. “The Trump vote may mirror that. It’s the anger at being overlooked, at not having an opportunity, and not being part of the national narrative.

“If you live in an area with high opioid use, you’re going to be very angry, and that won’t change even if you are fine. People living in these areas share the feeling that the country is not going in the right direction,” he continued. Such voters may have been more likely to relate to Trump’s populist message of “Drain the swamp,” Goodwin added.

Researchers found a 16 percent overlap between a county’s Trump vote percentage and the percentage of adults using chronic opioids, a strong association, Goodwin said. While two-thirds of this overlap was explained by collected socioeconomic data, that does not mean such factors were not in play for the remainder. “Our interpretation is that if we had more complete socioeconomic indicators—of how people were thriving in their communities or not—that would explain all of the overlap.”

Goodwin said one conclusion of the study is that public health policy directed at stemming the opioid epidemic must go beyond the medical model that focuses on prevention, diagnosis, and treatment protocols. Rather, it should also incorporate socioenvironmental disadvantage factors and health behaviors into policy planning and implementation.

The study also sheds light on the differences in physicians’ opioid-prescribing habits county by county that are fueling the opioid epidemic in some areas. Neary one-tenth of an enrollee’s odds of receiving prolonged opioids was determined by what county in which he or she resided, even after adjusting for enrollee characteristics. Counties with the highest long-term opioid prescribing rates were predominantly concentrated in Appalachia and the South, as well as Michigan and some Western states.

Limitations of the study are that it included the presidential votes of all voters in counties studied, while the prolonged opioid prescription data were gleaned only from a sample of Medicare Part D enrollees, who are elderly or disabled and therefore may not represent the nation as a whole.

“The study is done quite well, for what they are trying to do,” said Andrew J. Saxon, M.D., chair of APA’s Council on Addiction Psychiatry and a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the University of Washington in Seattle, who reviewed the study at the request of Psychiatric News. “They make it clear there is no way to attribute causation, that they cannot say the opioid prescribing rate plays a causal role in voting for Trump.”

Saxon said long-term efforts for preventing opioid use disorder may require enhancing early childhood education, particularly for children in at-risk families, which has been shown to reduce substance use risk in adulthood, as well as addressing the obesity epidemic, which fuels joint problems and chronic pain that may lead to long-term use of opioids.

The study was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health. ■

“Association of Chronic Opioid Use With Presidential Voting Patterns in U.S. Counties in 2016” can be accessed here.