Study on Opioid Deaths Shows Need to Offer Substance Use Treatment for Chronic Pain Patients

Abstract

An analysis of health service use prior to opioid-related deaths reveals the intersection of chronic pain and prescription drug use in the opioid epidemic.

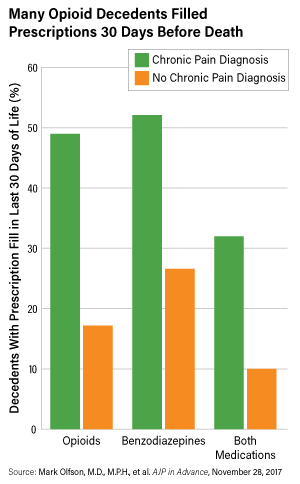

Most people who died from opioid overdoses were diagnosed with a chronic pain condition in the last year of life and close to a third of them filled prescriptions for both benzodiazepines and opioids in the 30 days prior to death, according to a report in AJP in Advance.

Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., says dropout from treatment of substance use disorders may be common in the months preceding opioid-related deaths.

The analysis of health service use patterns in a population of Medicaid patients in the year preceding a death related to opioid use reveals the striking overlap between chronic pain and the epidemic of opioid deaths in the United States, and the need to better coordinate substance use disorder and pain treatment.

It also points to the danger of dual use of opioids and benzodiazepines, according to lead author Mark Olfson, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of psychiatry and epidemiology at Columbia University.

“Thirty-two percent of decedents filled prescriptions for both opioids and benzodiazepines in the last month of life,” Olfson told Psychiatric News. “Given their additive effects on respiratory suppression, great caution should be exercised in prescribing this potentially dangerous medication combination.”

Olfson and colleagues analyzed data on opioid-related deaths for 45 states from the 2001-2007 national Medicaid Analytic Extract data from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (Arizona, Delaware, Nevada, Oregon, and Rhode Island were not included.) Opioid-related deaths were divided into those that were preceded by at least one inpatient or two outpatient claims for noncancer pain diagnosis in the last year of life and those that were not.

Dates and cause of death information on the study decedents were derived from linkage to the National Death Index, which provides a complete accounting of state-recorded deaths in the United States and is the most complete resource for tracing mortality in national sample. Olfson and colleagues restricted the sample to decedents who were continuously enrolled in the Medicaid program for at least 12 months prior to death.

Among the 13,089 opioid-related decedents, 61.5 percent were diagnosed with at least one chronic pain condition during the year prior to death. This included 59.3 percent who were diagnosed with back pain, 24.5 percent with headaches, and 6.9 percent with neuropathies. Nearly all decedents in the chronic pain group were also diagnosed with other bodily pain conditions.

Roughly two-thirds of all persons with fatalities filled opioid (66.1 percent) and benzodiazepine (61.6 percent) prescriptions during the last 12 months, and approximately half (50.2 percent) filled both. Prescriptions for antidepressants (59.0 percent), antipsychotics (31.6 percent), and mood stabilizers (35.4 percent) were also commonly filled during this period.

Other striking findings from the analysis include the following:

Approximately one-third (33.6 percent) of decedents were diagnosed with drug use disorders in the last year of life; similar percentages of patients received diagnoses of opioid use disorder (13.6 percent) and alcohol use disorder (13.3 percent).

Despite the frequency of drug use disorder diagnoses in the 12 months preceding opioid-related death, relatively few (4 percent) were diagnosed with opioid use disorder in the preceding 30 days. While the lack of a diagnosis within that month does not necessarily indicate lack of treatment, Olfson said it is a reasonable proxy for low frequency of clinical attention to opioid addiction.

The most commonly diagnosed non-substance-use mental disorders during the last year of life were depression (23 percent) and anxiety (19 percent). These were followed by bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorder, and other mental disorders.

Olfson told Psychiatric News that the analysis of prescription data did not include information on provider specialty. “It would have helped to define the role of psychiatrists, given that so many of the decedents were diagnosed with depression or anxiety in the last year of life,” he said.

Individuals with diagnoses of chronic pain were significantly more likely than those without this diagnosis to have been prescribed opioids, benzodiazepines, or both within 30 days before an opioid-related death.

It is also not possible to know from the data if patients received multiple prescriptions from the same provider. Acknowledging the phenomenon of “drug seeking” among individuals with opioid use disorder, Olfson cited a recent report by the state of Massachusetts showing that 35 percent of males and 61 percent of females who died of opioid overdose in the state had three or more physicians prescribing a scheduled drug to them. “These patterns underscore the importance of using Prescription Drug Monitoring Program data in prescribing decisions,” Olfson said.

He said that in addition to the danger of using both benzodiazepines and opioids, several messages emerge for clinicians and prescribers of psychotropic medications from these patterns of service use before fatal opioid overdose. “First, there is substantial overlap between chronic pain and opioid fatality,” he said. “Over half of decedents were diagnosed with at least one chronic pain condition in the last year of life. This suggests a need to coordinate substance use treatment services with pain centers and clinics.”

Olfson also said the striking paucity of diagnoses for opioid use disorder in the 30 days prior to an opioid-related death suggests that drop out from drug treatment or clinically undetected opioid use disorder are common prior to opioid-related death. “Because opioid use disorder is a persistent and relapsing disorder requiring ongoing treatment, low rates of diagnosis in the last month strongly suggest greater clinical efforts are needed to improve clinical detection and ensure ongoing medication assisted treatment for those with opioid use disorders.” ■