Healing at the Isenheim Altarpiece

Abstract

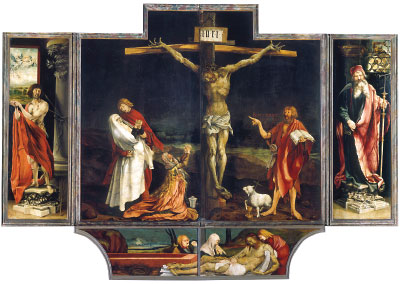

People have often called it one of the world’s masterpieces, one with healing properties. Mathis Gothart Nithart, known as Grünewald, painted the panels of the Isenheim Altarpiece, and Nikolaus Hagenauer created its sculptures. The collective work stands in Colmar’s Musée Unterlinden. Colmar is a small French city in Alsace, a region in northeast France. The altarpiece was built between 1512 and 1516 for the altar of the church in St. Anthony’s monastery in the Alsatian village of Isenheim.

As Pantxika Béguerie-De Paepe and Magali Haas describe it in The Isenheim Altarpiece (2015), the altarpiece takes “the form of a polyptych with multiple, hinged panels closing over a central section. … The altarpiece offered pilgrims and the sick a reading of the Passion of Christ, from the Annunciation to the Last Judgment, along with episodes from the life of Saint Anthony.”

An early Christian mystic, St. Anthony reportedly lived on bread, salt, and water as a recluse in a desert hermitage until his death in the fourth century. Stories abound about his repeated struggles with Satan in the forms of dreams and visions. But Anthony eventually won the battle, augmenting his reputation as a healer and miracle worker (a thaumaturge). His name was linked to the healing of a severe chronic disease called St. Anthony’s Fire. Anthonite hospices, such as the one at Isenheim established around 1300, are said to have concentrated on the care of patients with this and other skin diseases.

Mathis Gothart Nithart, dit Grünewald; Retable d’Issenheim (fermé), vers 1512-1516; Colmar, Musée Unterlinden.

St. Anthony’s Fire, also known as ergotism, resulted from eating bread tainted with a parasitic fungus that infected rye. Early signs of the disease were prickling and tingling of the limbs, which often progressed to severe burning pain, and necrotic tissue in the extremities. Convulsions, hallucinations, and pronounced pockmarks on the skin were said to be prominent symptoms of the illness. Béguerie-De Paepe and Haas described a ritual during which patients were taken in front of St. Anthony’s image in the altarpiece and given a special drink in which relics of the saint had been dipped and containing plants with vasodilating or anesthetic properties. The caregivers also applied a balm to the skin. The disease was known for its morbidity and mortality.

The main panels of the altarpiece emphasize “suffering.” Christ’s crucified body is centrally positioned, with his head fallen on his chest and crowned with thorns. His body is thin and battered, marked and bloodied by soldiers’ prodding. Béguerie-De Paepe and Haas suggest that this powerful image of the crucified Christ reminded pilgrims and patients, as they entered the Isenheim church, of the price of salvation; and that their suffering “was negligible compared with that endured by Christ.” The predella, the horizontal panel below the central one, shows Christ before he is entombed. The Virgin Mary’s tears are visible. Mary Magdalene’s eyes are red from weeping, and the crown of thorns sits on the floor. There is the image of St. Sebastian (known as a protector against plague) on the left panel and St. Anthony on the right panel. Their presence is justified because both were popular thaumaturgic saints. St. Anthony appears on other panels, indicating his honored status in this altarpiece.

Despite the marked suffering in the images of the altarpiece, I marveled at the therapeutic efforts of the caregivers in 16th century Alsace. Yes, there was emphasis on the body geography: the body’s assaults, deterioration, and martyrdom—its ultimate loss of dignity. But what also shines through are the caring and uplifting of the human spirit, inspiring hope and nursing the suffering of others.

The effects of the disease were appreciated too well for there to be talk of a recovery movement. And so, the saints served their purpose. This was the early 1500s, remember. It was quite an experience for me to see this proof of an early healing community. ■