Community Mental Health and Deinstitutionalization

Abstract

Throughout its long history, APA has fought to improve the care of people with serious mental illness in the United States, but the government still fails to do its part.

In the 175 years since APA was begun, there have been several eras of major reform. The first, which coincided with APA’s founding as the Association of Medical Superintendents of Institutions for the Insane in 1844, was the Moral Treatment era and asylum movement. This movement was spurred by the extraordinary advocacy of Doreatha Dix in concert with several of the founders, moving patients from poor houses and jails into humane asylums built in rural areas far from the city and its turmoil, which was considered necessary to cure mental disorders. The Mental Hygiene Movement of the early 20th century was a second era that prioritized prevention of mental illness and advocated a much broader scope for care and treatment than inpatient hospitalization. But for 100 years, the original asylums of Dorothea Dix and those early psychiatrists, called “alienists,” persisted and morphed into large custodial institutions at state and county expense. The hope of so-called Moral Treatment gave way in the next century to a much more pessimistic view of mental illness and the warehousing of thousands of individuals.

By 1955, the peak of public asylum psychiatry was reached. Well over half a million individuals were hospitalized in institutions throughout the country. The average length of stay was nine months, but many had spent a lifetime hospitalized. The winds of change came in that year with the introduction of chlorpromazine and soon after other first-generation antipsychotic medications. Recognition that long-term institutionalization itself led to “social breakdown”—that is, symptoms related to long-term “total” care rather than illness itself—was reinforced by concerns about the civil liberties of individuals being held for such long periods.

The high costs incurred by states was also a major factor in rethinking institutional care. A new ideology began to grow within the psychiatric community that focused on care close to where people lived and worked, embodied in the newly established National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) under the leadership of psychiatrist Robert Felix, M.D. In July 1955, Congress unanimously passed the Mental Health Study Act, which required NIMH to appoint a “joint commission” to Congress to plan and conduct a thorough reevaluation of the nation’s approach to the treatment of people with mental illness. Jack Ewalt, M.D., then treasurer of APA, was chosen commission director.

The commission was in existence for five years, collecting a nationwide consensus on the need for major reform of mental health services. Its 1961 report, titled “Action for Mental Health,” laid the basis for the Community Mental Health Centers Act of 1963. President John F. Kennedy signed the legislation, which was intended to provide federal funds for the construction and staffing of comprehensive community mental health centers (CMHCs) in “catchment areas” of between 75,000 and 200,000 individuals across the country. The hope was that the entire country would be covered by the mid-1970s, but that did not come to pass.

Local communities applied for federal funds that declined over several years (initially five years and then eight). Alternative funds, especially third-party payments, were expected to replace the declining federal grants. The federal grants provided the essential structure to manage the eventual depopulation of state and county mental hospitals and the provision of care and treatment in alternative community-based settings. CMHCs were initially required to have five essential services. These included short-term inpatient care, day hospital services, outpatient services, and “consultation and education services.” The hope was that the federal grants would leverage state budgets to move services into community settings.

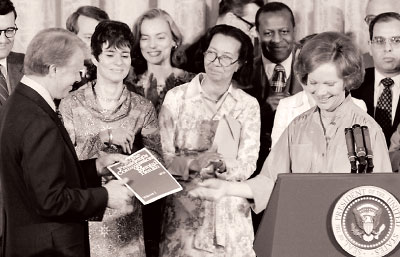

Rosalynn Carter, who served as honorary chair of the President’s Commission on Mental Health, presents the commission’s final report to President Jimmy Carter in April 1978. She continues to be one of the country’s leading advocates on mental health reform.

The program survived several reauthorizations and amendments, as well as the Nixon administration’s effort to repeal and abolish it. APA was involved in the preservation of the program and the passage of the Carter administration’s Mental Health Systems Act of 1980. This act passed with the advocacy of First Lady Rosalynn Carter. It expanded federal dollars as well as the scope of the CMHC program with a major emphasis on the care and treatment of people with serious mental illness. Ronald Reagan, however, was elected that year, and by 1981 the law was repealed and funding moved to a block grant program. This essentially ended the CMHC program, which covered about half of the country by that time. APA leaders prominent in advocacy for CMHCs included Herbert Pardes, M.D., Joseph T. English, M.D., and John Talbott, M.D., all of whom were APA presidents.

As we know, deinstitutionalization has had its downside. Many of the patients were discharged into unprepared communities and ended up being “transinstitutionalized” to jails, prisons, and nursing homes. Today we have fewer than 110,000 psychiatric beds—and only 37,000 in state and county hospitals, the majority of which are occupied by patients ordered for treatment and evaluation by the courts.

The promise of community mental health and community psychiatry remains, and it is the most urgent public health issue of our day. The numbers of mentally ill individuals who are homeless or incarcerated is a national disgrace. Leadership by APA is a critical factor in providing humane options for these patients, who continue to suffer; are largely stigmatized by the communities from which they come and where they live; and can benefit from treatment, housing, and other support. ■